Review | Book review: the bloodiest Vietnam war battle, Hue, 1968 – a searing account of courage and cowardice

Bestselling author of Black Hawk Down uses the same grunt-level reporting style to highlight horrors of war and the arrogance and incompetence of US military leaders during pivotal, 24-day battle to recapture overrun city

Hue 1968: A Turning Point of the American War in Vietnam

by Mark Bowden

Atlantic Monthly Press

4 stars

To understand why, Mark Bowden’s searing Hue 1968: A Turning Point of the American War in Vietnam takes us deep into the bloodiest single battle of that bitter conflict, tracking Americans and Vietnamese as they fought house-to-house for a city that came to symbolise the folly of the war.

It began on January 31, 1968, when tens of thousands of North Vietnamese regulars, Viet Cong guerillas and local communist militias suddenly launched more than 100 simultaneous attacks on US military bases and cities across South Vietnam, an audacious assault that caught the Pentagon utterly by surprise.

The Tet Offensive, named for the start of the Lunar New Year, stunned the White House and the American public, who had been assured that nearly half a million US combat troops had the enemy on the run and victory was nigh. After all, more bombs had been dropped on North and South Vietnam by 1968 than were dropped in Europe during all of the second world war.

Book review – Blood & Silk: Power & Conflict in Modern Southeast Asia offers a bleak prognosis for region’s future

Instead, American TVs showed hardened enemy soldiers shooting their way into the fortresslike US embassy compound in Saigon, the very symbol of American power and resolve, and fighting for hours with US marines.

The Tet Offensive failed in its stated objective: sparking a popular uprising that would overthrow the US-backed regime in Saigon and force US troops to leave. Instead, the attackers were beaten back nearly everywhere in the first few hours or days.

Everywhere but Hue, that is.

Thousands of North Vietnamese and Viet Cong had quickly overrun Hue, a once elegant city of French colonial buildings and royal palaces along the Perfume River. They dug in, defiantly raised their flag atop the walled citadel, and tried unsuccessfully to rally civilians to their authoritarian cause.

A small US military compound had held on but was cut off. And reinforcements were agonisingly slow to arrive since commanders in Saigon and Washington refused to acknowledge that Hue was firmly in enemy hands even as the body bags piled up.

Sweeping new history of the cold war a reminder of how stupidity, ignorance and arrogance almost brought the world to annihilation

It took outnumbered Marines and soldiers – as well as navy warships firing huge guns offshore – 24 harrowing days to recapture Hue, and by then most of the nation’s cultural centre was in ruins. Bowden estimates more than 10,000 people died, including 250 US military personnel, in the city.

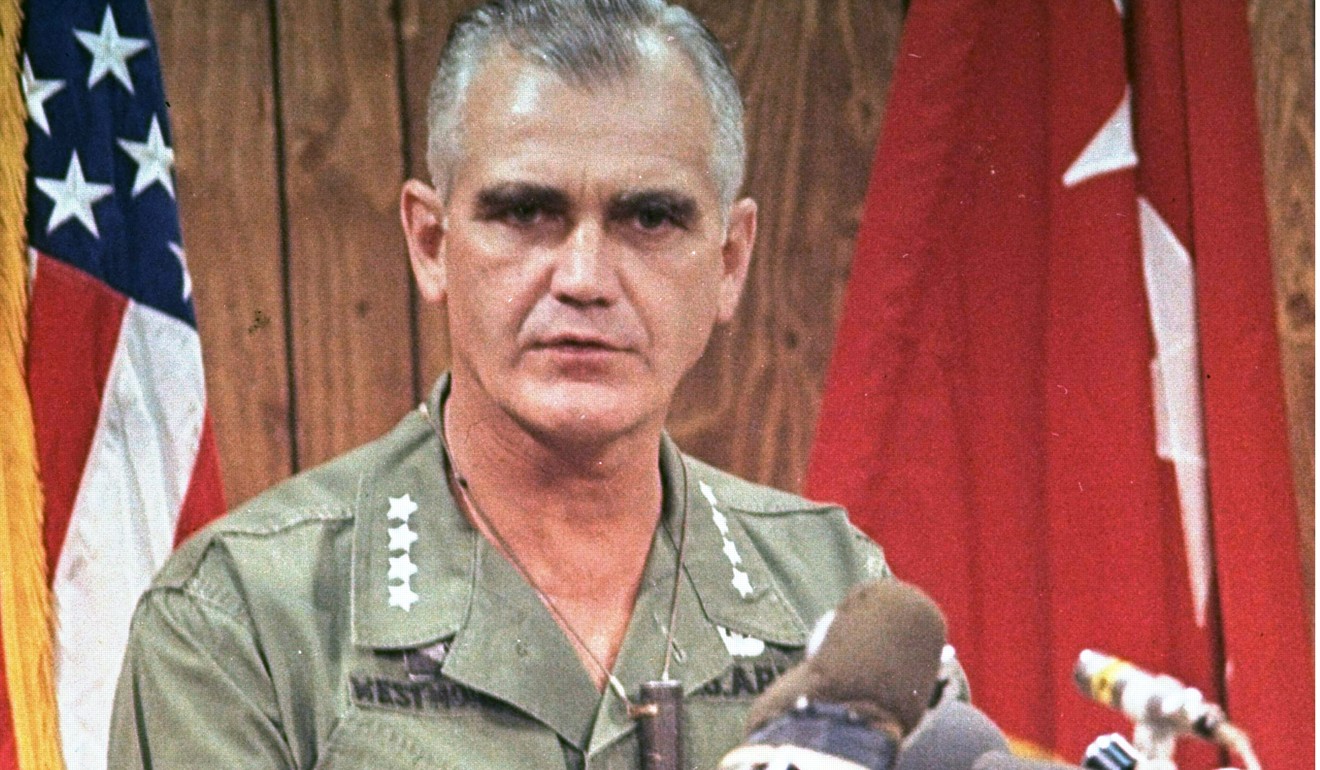

In that entire period, General William Westmoreland, then the US military commander, inexplicably insisted that the enemy’s real target was a remote US base called Khe Sanh – and that Hue was just a diversion.

Wearing blinders is one thing. Wilful duplicity is another. At no point did Westmoreland acknowledge to the White House, the Pentagon or the press that his men were in a ferocious battle to reclaim the country’s third-largest city from a disciplined, well-armed and entrenched enemy. The grisly truth emerged only because reporters risked their lives on the front lines.

Bowden revisits the historic battle with the same character-driven, grunt-level reporting style that made his earlier Black Hawk Down a bestseller. He lends a sympathetic ear to surviving soldiers on both sides as well as guerillas and civilians, and gives a vivid account of courage and cowardice, heroism and slaughter.

Bowden doesn’t pull punches about the cruelty on both sides. In one painful interview, a former Marine tells Bowden he is tormented by the memory of when he and his buddies lined up to have sex with a desperate refugee, paying her with rations to feed her family. Only one member of the squad opted out.

The Viet Cong commander in the citadel was convinced Marines used civilians as human shields. And some Marines did see every civilian as a “Charlie”, an enemy worth killing. In any case, Bowden figures allied shelling and bombing probably killed more civilians than any other cause.

But he also recounts how young communist zealots systematically rounded up and executed hundreds, perhaps thousands, of Hue’s civil servants, from professors to policemen, during the occupation. The true figure will never be known.

In his spellbinding Black Hawk Down Bowden chronicled the American miscalculations that led to a single deadly clash in Mogadishu in 1993. The battle in Hue lasted weeks and involved devastating US intelligence failures, appalling leadership and furious battles in multiple sites. The lengthy narrative thus is more of a challenge. And one wishes to hear more from the determined North Vietnamese soldiers who fought as bravely as the Marines. This book leans heavily on American accounts of the fighting.

Bowden concludes that the nightly TV pictures of carnage in Hue marked a pivot point in US history. After it ended, the debate “was never again about how to win but about how to leave. And never again would Americans fully trust their leaders”.

The blood letting, and the lies, would only intensify under President Richard Nixon. The war would grind on seven more years before North Vietnamese tanks rolled into Saigon. This time the TVs showed Americans crowding onto helicopters at the US embassy and fleeing for their lives.