Author’s death rekindles obscenity debate in South Korea

Ma Kwang-soo’s banned 1991 novel Happy Sara, about a sexually adventurous female student, split opinion and took a heavy toll on the life of an intellectual who perhaps just lived far ahead of his time

By Kang Hyun-kyung

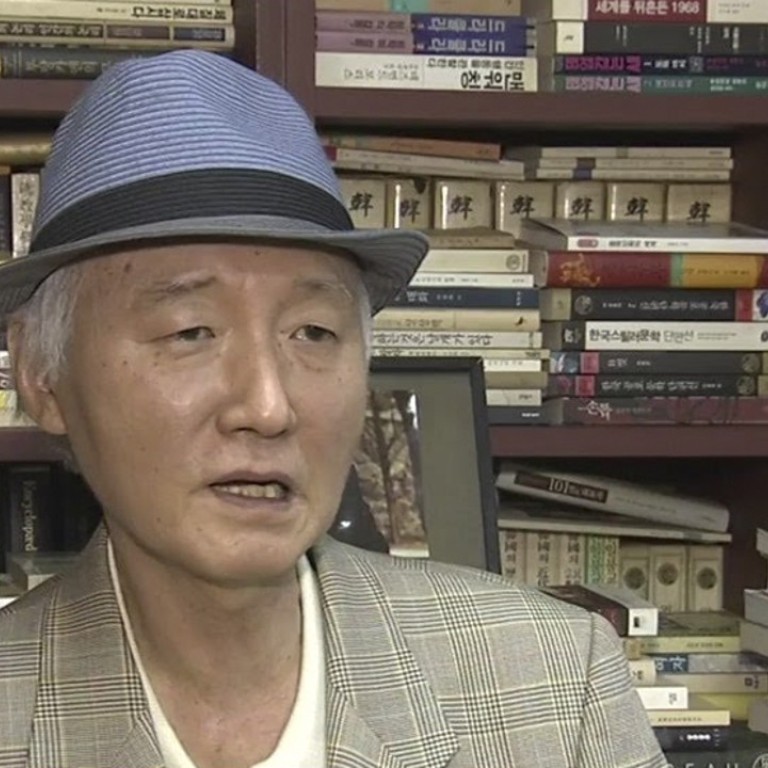

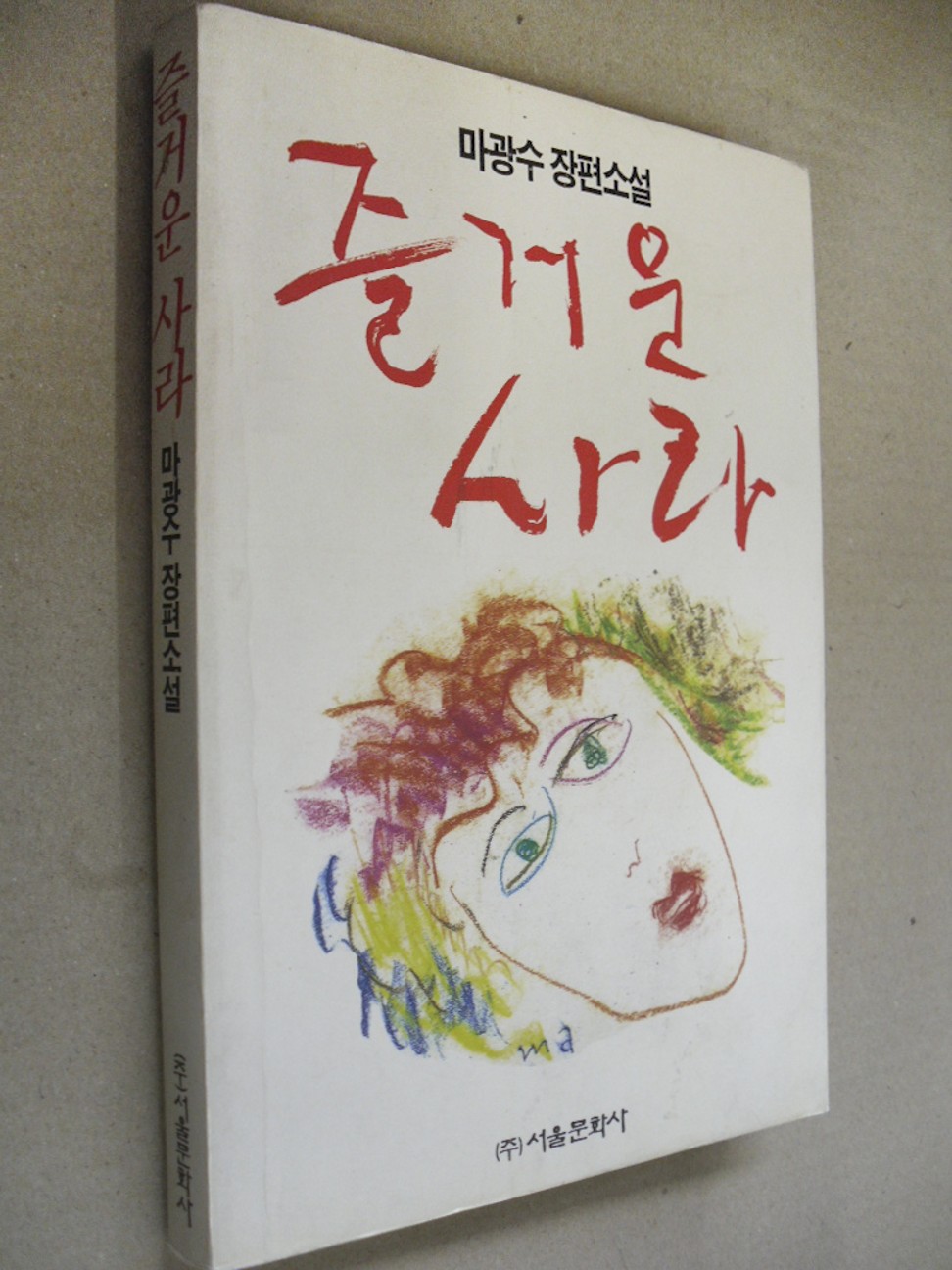

South Korean author and professor Ma Kwang-soo, who was found dead on September 5, is still at the centre of controversy for his watershed fictional work Happy Sara. The book was banned in 1992 for “depraving and corrupting” the younger generation. In the same year, the court sentenced Ma to an eight-month jail term, suspended for two years, for “creating and disseminating obscene materials” in the guise of a literary work.

A posthumous debate about the author continues about whether he was an intellectual who had lived way ahead of his time and was consequently persecuted, or an unrepentant social outcast.

South Korean literature has come of age, writes Man Booker winning translator

Happy Sara, published in 1991, described in great detail the life of college student Sara, who follows her sexual desires and explores various unconventional sexual relationships. Her affair with a married professor, sex with her girlfriend, and frequent one-night stands were explicitly described in the fiction with the frequent use of words deemed as unfit for publishing.

Ma, a former professor of literature at Yonsei University and the author of 60 books, including essays, poetry collections and fiction, was found dead in an apparent suicide at his home in Seoul. Those who are familiar with him said he suffered depression and had difficulty making ends meet after retirement because he spent all his fortune on his legal fights.

His death has sparked heated debate about the banned book, as well as sales for his other books.

According to South Korea’s largest offline bookstore Kyobo and largest online bookstore Aladin, more than 1,500 copies of his books have been sold since his death – a surprising figure, considering only one or two were sold per month before his death.

Meanwhile Naver, the nation’s largest internet portal, showed that Ma’s death had rekindled debate about Happy Sara on social media, 25 years after it was banned.

“Ma’s arrest and ensuing conviction because of Happy Sara shows how excessive and barbarian the law enforcement officials were when they executed the law,” literary critic Hwang Hyun-san lamented on Twitter to commemorate Ma’s death. “The law is there to protect freedom of expression, not erode it.”

Han Seung-heon, a lawyer who defended Ma during the 1992 trial, said things might have turned out differently if the case were taken to court now.

Depending on the judges, he said Ma could have avoided a conviction if a judge had been convinced that Happy Sara, despite its explicit descriptions of sexual relationships, had some literary value.

Move over K-Pop, the next Korean culture wave could be K-Lit – if enough great books can be translated well

His remarks indicate that Korean society today has become more tolerant of different views and perspectives about various topics, including sexuality, compared to 25 years ago, while experiencing a surge of publications and materials dealing with such topics.

“The controversy over the 1992 ruling about Happy Sara has persisted over the past 25 years, because the initial ruling has left room for debate,” Han said.

He added he was convinced Ma was not guilty after conducting a thorough textual analysis of Happy Sara when he defended Ma in the courtroom.

“Its content as a whole was not something punishable under the anti-obscenity law. So I pleaded not guilty for him,” he said. “There has been no change in my opinion since 1992.”

As Ma said in his retirement speech at Yonsei University in 2016, Happy Sara took a heavy toll on his life. He was arrested on violations of the anti-obscenity law while teaching a class of students in 1992, and was later convicted. He appealed, but in 1995 the Supreme Court upheld the initial ruling from the Seoul Central District Court.

I believe the public appeared to have been confused between the character he created in his fiction and the real Ma

In the courtroom, his book became an object of ridicule. It was described by legal and literary experts, who were called there as witnesses, as “toxic waste” and “a junk product” that had no literary value.

Ahn Kyung-whan, then a law professor at Seoul National University, said Happy Sara had no literary, artistic, political or social merit whatsoever and thus was not in the interest of the public good, which paved the way for the court’s decision that the story was just obscene material.

The ruling drew the ire of other literary figures, as well as liberal activists. They criticised the law enforcement authorities for their “abusive” use of the anti-obscenity law and violations of freedom of expression. They alleged those who were involved in the ruling were out of touch with changing social norms.

What first short stories smuggled out of North Korea say about life in the hermit state, and their challenges for a translator

Some media outlets raised a right-wing conspiracy theory. They reported that Ma had become a target of a premeditated witch hunt driven by a handful of ultra-right figures, including then prime minister Hyun Soong-jong, who were unhappy that the book had caused an unnecessary social problem.

According to those media outlets, Hyun directed the prosecution to arrest and persecute Ma for a series of his works that caused a stir about existing moral values and social norms.

The ruling about Happy Sara wreaked havoc on Ma’s life. He was fired from his university job in 1995 after the Supreme Court confirmed his crime. He did, though, manage to return to his teaching job in 1998 after being granted a special pardon following years of advocacy activities carried out by liberal activists and his students.

The way I look makes me sad. My hands are tied with rope because I wrote a novel. I go through this ridiculous suffering just because I was born in this hopeless country

His on-campus struggles, however, continued. In the early 2000s, he failed his university’s re-evaluation of faculty members – for “underperformance” in research and academic activities. He was reinstated after years of legal battles against the decision.

Ma said he was traumatised by such experiences and suffered lingering depression from a sense of betrayal by his fellow faculty members. Ma said he was a loner at the university.

Conservative journalist Cho Kab-je shed light on a lesser-known aspect of Ma. In his website posting, titled “Commenting Ma Kwang-soo”, Cho challenged the 1992 ruling and described Ma as a normal professor who liked teaching and reading, not much different from other academics, and with apparently no intention to agitate society.

“Living in a society flooded with various obscene materials, I wonder why people felt so offended particularly by his book,” he wrote.

“Was this because he was a professor at a prestigious university? I believe the public appeared to have been confused between the character he created in his fiction and the real Ma, and he was painted as an obscene writer. Society punished him in the name of justice. I don’t know whether it was appropriate or not.”

Han Kang, author of Booker winner The Vegetarian, whets Koreans’ appetite for literature

In his last poem, titled Sara’s Courtroom, Ma described the silly atmosphere of his trial and ridiculed the hypocrisy of society. He wrote:

“The head judge tried hard to manage his facial expressions so he would look serious. He asks me if I would recommend Happy Sara to my daughter, if I had one.

“He made me wonder why he’s worried so much about daughters, not sons … Another judge to his left was yawning, while the third one on the right had a sadistic smile on his face.

“The way I look makes me sad. My hands are tied with rope because I wrote a novel. I go through this ridiculous suffering just because I was born in this hopeless country.”