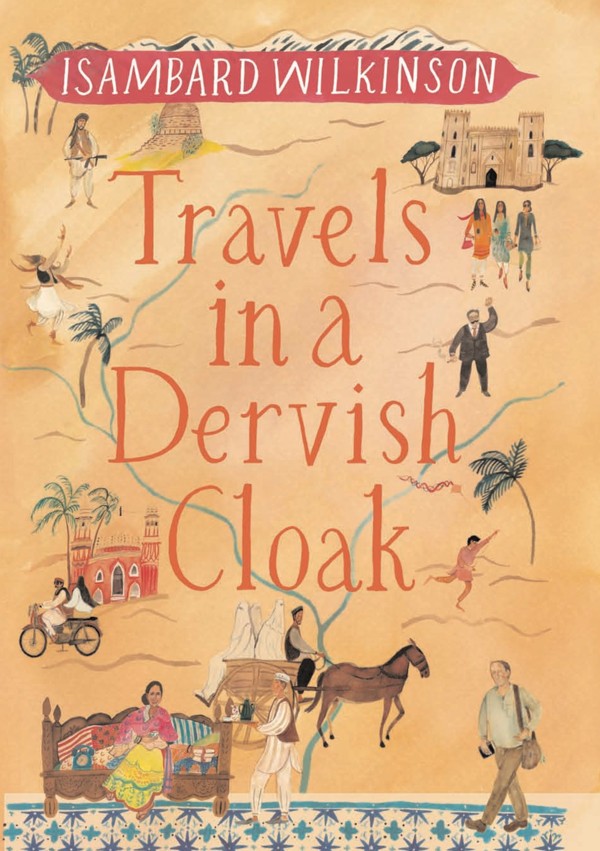

Review | Book review: Travels in a Dervish Cloak reveals the real Pakistan – its characters, charms and challenges

For many outsiders, Pakistan remains an amorphous entity in negative news reports, but Isambard Wilkinson’s charming, old-style travel book redresses the balance by revealing the complex patchwork of the real country

by Isambard Wilkinson

Eland

4.5 stars

Pakistan was once prime territory for Western travel writers. It offered an attractive combination of subcontinental colour and Central Asian romance, plus a lively history and a hospitable population speaking excellent English. Geoffrey Moorhouse, Dervla Murphy and Wilfred Thesiger passed this way, among many others. In The Great Railway Bazaar, Paul Theroux even pondered the attractions of Peshawar as a place of retirement.

But since the launch of the “war on terror” in neighbouring Afghanistan, and subsequent instability in Pakistan itself, the bulk of the books written by foreigners about the country have been made of sterner stuff: bleak journalistic or scholarly commentaries from the likes of Anatol Lieven and Owen Bennett-Jones.

Book review: China as a Polar Great Power – as polar sea lanes open up, what are China’s plans?

This is what makes Isambard Wilkinson’s Travels in a Dervish Cloak such a welcome delight. Although the author is himself a professional journalist – formerly The Daily Telegraph’scorrespondent in Islamabad – he has made of his time in Pakistan a charming, old-style travel book. He reminds us of the complex humanity and considerable charms of the place, facets often obscured in more strictly analytical accounts.

The “dervish cloak” of the title is Pakistan itself – a raggedy patchwork garment, in a phrase borrowed from Lahore’s patron saint, Data Ganj Bakhsh. The “travels”, meanwhile, are less a single journey than a series of forays from Islamabad, made during the author’s spell as a correspondent there between 2006 and 2009.

This was a turbulent period for Pakistan, encompassing the final years of Pervez Musharraf’s presidency, the lawyers’ protests which helped bring about its end, the bloody siege of the Islamist Lal Masjid mosque in the capital, and the assassination of female Pakistani politician Benazir Bhutto. These events all feature in the book, but they are secondary to what Wilkinson suggests was his true purpose in going to the country: a quest for “the essence, the quiddity of Pakistan, which I hoped to find by encountering its mystics, tribal chiefs and feudal lords”.

For Wilkinson, Pakistan was not simply a professional posting. His relationship with the country was already an old one, forged via his grandmother, scion of a Raj-era Anglo-Indian family, and her lifelong friendship with a formidable Pakistani woman, Sajida Ali Khan – known simply as “the Begum”. This personal connection led to Wilkinson’s first teenage visit to Lahore – “a place of enchantment” – and although returning as a journalist, his youthful backpacker’s sense of wonder remains intact, informing the warmth and enthusiasm of the book.

Book review: the bloodiest Vietnam war battle, Hue, 1968 – a searing account of courage and cowardice

The author has a knack for catching the characters of those he encounters during his journeys, and for sketching their physical presence: a tribal chieftain, for example, has “powerful shoulders and a martinet’s rigid backbone, with a long nose curled over a moustache, the tips of which he preened upwards into tusks”. There are other fine phrases too, such as the description of a tiresomely pious general who leans “on his ideology like a walking stick”.

The book also provides a strong sense of place through its descriptions of landscape and atmosphere, whether in the high mountains of Chitral or in the softer countryside around Islamabad. Wilkinson is particularly adept at catching the hectic scenes during festivals or on city streets.

The author has a good ear for the conversational rhythms of Pakistan’s anglophone middle classes – particularly during their booze- and cannabis-fuelled parties – and he also makes entertaining material from the wrangling and rivalry among his household staff. In this, Travels in a Dervish Cloak obviously recalls William Dalrymple’s City of Djinns. While Wilkinson doesn’t quite match Dalrymple’s scholarly engagement with history, he does have a similar fascination with the syncretic traditions of South Asia, especially in Pakistan’s threatened Sufi places of worship – “epicentres, pulses of Old Pakistan” as he calls them.

There are a few minor complaints. Travel writing by Westerners about countries such as Pakistan is often accused of having a troublesome colonial heritage. So why provide easy ammunition for critics by using the dated Raj-era ethnic designation “Pathan” for the people of Pakistan’s western borderlands, instead of the modern “Pashtun”? And it is a shame that a book which seems intent on producing an affectionate portrait of Pakistan in the round gives no coverage to the region of Gilgit-Baltistan and “Azad” Kashmir.

The Stolen Bicycle: Wu Ming-yi expertly weaves a narrative of Taiwan

Not only is this a physically spectacular and culturally fascinating region, but its “disputed territory” status is key to Pakistan’s dysfunctional relationship with India – something not explored in great detail here. However, these issues do nothing to diminish the book’s winning charm.

Travels in a Dervish Cloak is not without the stuff of serious journalism. There is a chilling first-hand account of the aftermath of the deadly bomb attack on Benazir Bhutto’s homecoming parade through Karachi in 2007; a thoroughly intrepid trip across the lines to meet the rebel Baluch chieftain Nawab Bugti (later killed during a clash with the Pakistan military); and hair-raising forays into the fringes of Taliban territory.

But where another book-writing journalist might have recounted all this in the mode of portentous reportage, Wilkinson consistently – and endearingly – deploys the time-honoured travel writer’s self-deprecation, even in extremis, much like Eric Newby.

Nonetheless, the book closes in a sombre mood. It describes the wheels apparently beginning to come off what Wilkinson calls the “Heath Robinson contraption” of the Pakistani state, with Islamist violence on the rise and a more general religious conservatism apparently pushing tolerant traditions towards extinction. The dark mood is exacerbated by the fact that the author’s stint in Pakistan was brought to a premature close by his own failing health (though he has since fully recovered and returned to reporting duties – in Hong Kong).

In the years since Wilkinson left Pakistan, the country has lumbered along. Violence and political crises have continued, but there have been positive turns here and there. The Taliban takeover of Swat valley – described towards the end of the book – is ancient history now; the nascent “China-Pakistan Economic Corridor” offers some prospect of future prosperity; and embattled secular society still endures.

Book review: The Golden Legend – beauty and pain in Pakistan

For many outsiders, however, Pakistan remains little more than an amorphous entity in negative news reports. Travels in a Dervish Cloak does an excellent job of redressing the balance by revealing the complex patchwork of the real country, home to diverse multitudes. In this it shows the great value of travel writing itself, when skilfully practised by such a humane, humorous and enthusiastic author.

Asian Review of Books