Hong Kong writers have much to say – and not just about democracy and politics

UK magazine Wasafiri dedicates an issue to exploring the city’s literature, and asks whether Hongkongers have a distinctive voice, if a local English writing style exists and if so, whether it has become mainstream

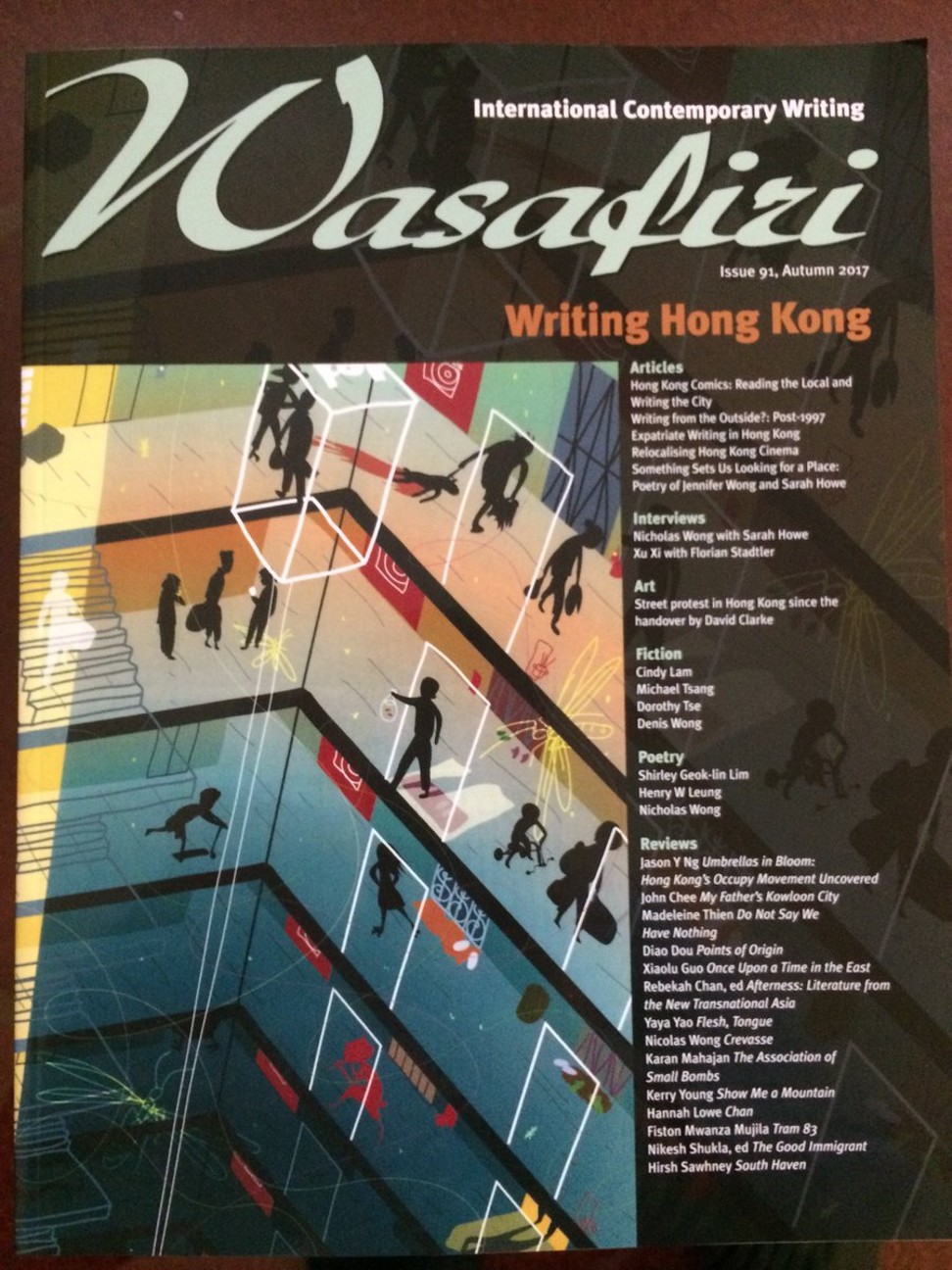

Is there such a thing as “Hong Kong writing” in English – that’s the weighty question British literary journal Wasafiri asks in its latest quarterly edition, devoted entirely to writing from the city.

Launched at the British Council in Hong Kong late last month and entitled “Writing Hong Kong”, the issue contains essays, interviews, reviews, original fiction and poetry. TS Eliot Prize winner Sarah Howe and Commonwealth Poetry Prize and American Book Award winner Shirley Geok-lin Lim are names whose reach clearly transcends the city; others such as Xu Xi, Jennifer Wong and Tammy Ho have established followings in the wider English-speaking world.

It is positioned as rather a serious and weighty undertaking: the essays are academic and intellectual in tone. These, plus the interviews and other non-creative prose outweigh the original poetry and fiction featured.

The Dictionary of the Asian Language reviewed: trivia tome reboots popular Asiaweek column

The journal’s editors, Jeffrey Mather and Florian Stadtler, say its blend of non-fiction articles, short fiction, poetry, and reviews is “the perfect forum through which to consider new critical and creative approaches that directly engage with Hong Kong’s geography, history, politics and poetics”.

One approach to the question Wasafiri poses is to shrug and take the position that Hong Kong writing is relatively easy to recognise – we know it when we see it – and a Hong Kong writer is one who produces Hong Kong writing and, second, has some concrete physical relation to the place.

Tammy Ho, in her essay “Something Sets Us Looking for a Place: Poetry of Jennifer Wong and Sarah Howe”, (gratifyingly) quotes my review of Howe’s debut collection Loop of Jade: “If there is such a thing as Hong Kong literature in English, Loop of Jade comes pretty close to it. And if there isn’t, Hong Kong would do well to claim Sarah Howe for its own regardless of what anyone else thinks.”

Ho then goes on to provide a gloss to this: “The reviewer’s tone here is ironic, although, one might also say, slightly defensive. It is as though he is pre-empting objections to Howe’s status as a Hong Kong poet or concerns that her poetry should not be viewed as Hong Kong literature.”

The editors, however, as well as several of the commentators, evidently feel something more than an ad hoc approach is needed.

Both Ho in her essay, and Grant Hamilton and David Huddart in “Writing from the Outside? Post-1997 Expatriate Writing in Hong Kong”, discuss the question in an academic way. Neither of Ho’s subjects lives in Hong Kong, although both did so once and have family roots in the city, but her conclusion seems to be that we know Hong Kong poetry when we see it.

Jung Chang talks Empress Dowager Cixi, flirting with a military dictator and advice from Imelda Marcos

Given that Hong Kong is the place it is, so-called “expat writing” occupies a great deal of brain space. Hamilton and Huddart use this lens to look at the vexing question of Hong Kong identity. One of their interesting observations is that the question of the expat/local divide is no longer, as it traditionally was, restricted to Caucasians. Singaporean poet Eddie Tay, a long-time resident, and Xu Xi, once a resident and now a peripatetic global citizen, are both discussed.

In places the essay does, however, get into the minutiae of the subject, notably the mention of a months-long spat between expat poet Kate Rogers and her reviewer that played out in the literary journal Cha.

While the question is not uninteresting, one is nevertheless left wondering whether – at a time when the Man Booker Prize has stopped trying to distinguish between American and British writers – it actually makes any difference.

Consistency sometimes being the hobgoblin of little minds, the book review section itself includes books from several writers who have no real connection to Hong Kong: Guo Xiaolu’s memoir Once Upon a Time in the East, Diao Dou’s short story collection Points of Origin, Karan Mahajan’s novel The Association of Small Bombs and a number of others.

Another issue lurking under the surface is whether Hong Kong writing is itself worthy of consumption, let alone study as writing rather than as a sort of political or social artefact. The editors, in their editorial, never actually make this claim nor attempt to demonstrate it; instead they write: “In the mainstream press, Hong Kong is dramatically, even tragically, represented as being embroiled in an epic struggle against an infinitely larger foe in the form of the Chinese Communist Party. Hong Kong is depicted as a castaway, an odd remnant of the British Empire, left to fight for itself.

“To us, this seems a distorted view and only part of the story of Hong Kong. Instead, upon closer reading, there are many other stories, some of which are deeply introspective and sometimes contradictory in terms of locating or understanding ‘Hong Kong identity’. We hope that this issue will open a window into these important debates and concerns.”

Fair enough; perhaps they feel that the quality of Hong Kong writing is self-evident. However, it is still the case that Hong Kong writing per se has not been terribly successful in broaching the literary mainstream.

Those writers and works which have done so are to some extent exceptions that prove the rule: Howe is a literary dual national; Janice Y.K. Lee, one of the most successful Hong Kong novelists (The Piano Teacher and Expatriates), decamped to New York.

Prize-winning Hong Kong-born poet Sarah Howe makes verse of city’s Basic Law

This issue of Wasafiri is perhaps not the place to make the case, but the case is worth making. Hong Kong poetry in particular can be vibrant, immediate and accessible; in an increasingly small and integrated world, Hong Kong writers have much to say – and not just about democracy.