Review | A lot of sex and Sanskrit: former monk’s record of his mission to democratise sexual love in Tibet shines in new translation

Gendun Chopel gave up his monastic vows and travelled to India in 1934 to ‘eliminate misconceptions about the passion of desire’; he writes of women’s equal role in the joys of sex – a break with traditional thinking at that time

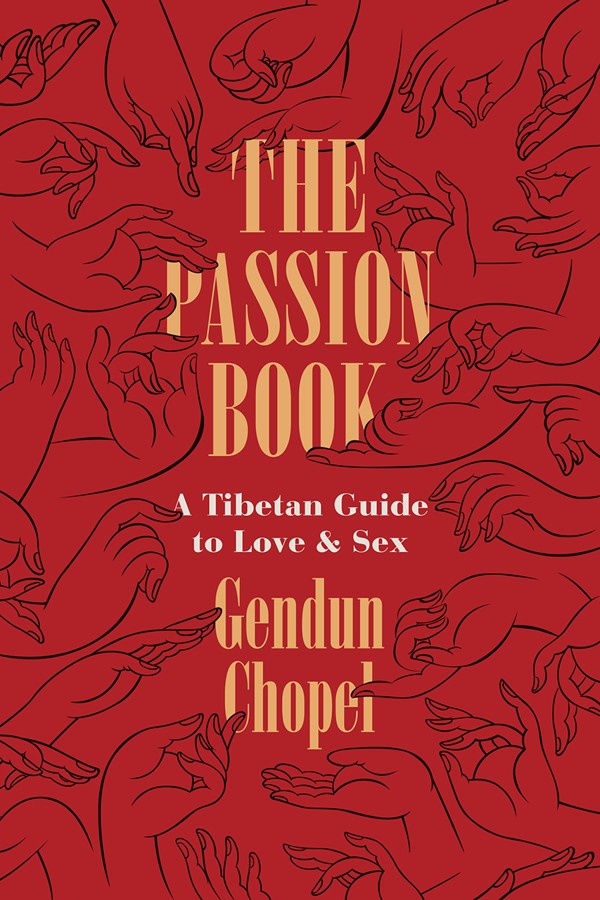

The Passion Book: A Tibetan Guide to Love and Sex

by Gendun Chopel (translated by Donald S. Lopez Jnr and Thupten Jinpa)

University of Chicago Press

4 stars

In 1934, Gendun Chopel, a former Tibetan monk, arrived in India in the company of an Indian scholar, Rahul Sankrityayan, just after giving up his monastic vows. He would remain there for some time before returning home in 1945, where he was arrested on a (probably) trumped-up charge of forging banknotes.

While in India, he lived in poverty as he wandered from place to place, gathering material for what would eventually become The Passion Book, a work completed in 1939 which started circulating in manuscript form and was eventually published in 1967, 16 years after its author’s death.

A new version, translated and with an afterword by Donald Lopez and Thupten Jinpa, has recently been published by the University of Chicago Press.

Indian erotic fiction, and openness towards sex, boosted by digital tech and stories where the underdog takes control

During his time in India, Gendun Chopel did two things: he had a lot of sex and he read a great number of classical Sanskrit texts, including, of course, the famous Kama Sutra. He even translated some of these texts into Tibetan.

In writing the poetry and prose in The Passion Book, Gendun Chopel had a serious purpose: he wanted to make sexual love in Tibet more democratic. He writes of “eliminating misconceptions about the passion of desire through hearing, thinking and experience”, which essentially describes what he was doing during his Indian sojourn.

Gendun Chopel believed that celibacy did not serve any purpose, and that it certainly did not enhance spirituality. For Buddhists, as the lengthy but essential afterword explains, sex was originally a product of something negative, namely human craving, brought on by curiosity and greed or desire.

The moral problem is that sexual pleasure is not bad, but sexual desire is. In the end, it was found that you can’t prevent sex, but you can regulate it, which is what happened.

Gendun Chopel sees this as hypocrisy: sexual pleasure, he writes, is really a force of nature and something which people of all classes and stations should be celebrating.

Religion teaches that sexual activity must take place at certain times, in certain places, with certain people and using certain orifices; Gendun Chopel sees this as condemning by day what the religious do at night. And in any case, if there were no sex, where would monks come from?

He celebrates the joys of sexual union as an equal action between men and women; “Let her do what she wishes,” he tells men, “to complete her pleasure.” Contrary to traditional practice, then, women are partners, not simply vessels for male pleasure or instruments of procreation.

“Swooning in the sleep of ineffable bliss,” he writes of a woman in ecstasy, “She dreams of the heavens making love to the earth.”

He opens his book with a section on “The Sexual Practices of Women of Various Lands”, showing how they have an equal (or sometimes) stronger sexuality than men, after which he moves to the techniques of lovemaking, at which point his book shows the obvious influence of the Kama Sutra.

The poetry often reads like a voyage of discovery; Gendun Chopel, after all, was in his early 30s before he had sex, and it’s this sense of wonderment which makes the book more entertaining and, indeed, more profound.

This excellent new translation admirably conveys the joy and beauty of the poetry as well as the underlying seriousness of Gendun Chopel’s work.

Asian Review of Books