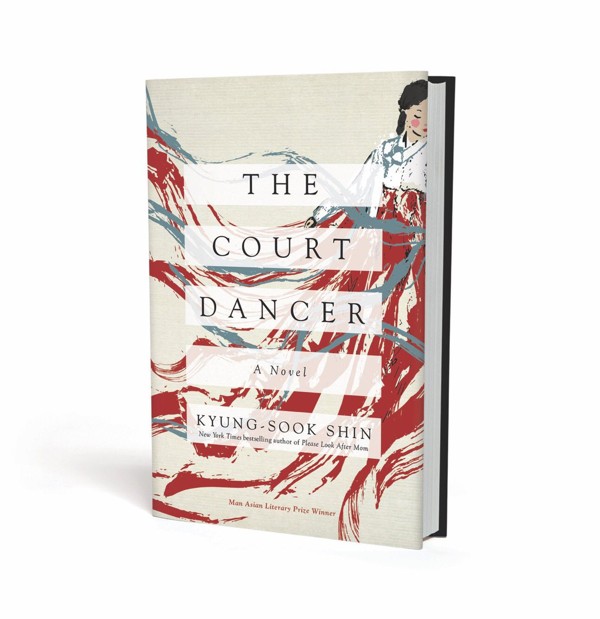

A Korean woman struggles in 19th century France in Man Asian Literary Prize winner’s latest book, The Court Dancer

In Shin Kyung-sook’s latest novel, a French diplomat falls for a Korean court dancer and whisks her off to his native France. She happens to speak French and impresses the literati, but is like a fish out of water and returns to Korea

by Shin Kyung-sook (translated by Anton Hur)

3.5/5 stars

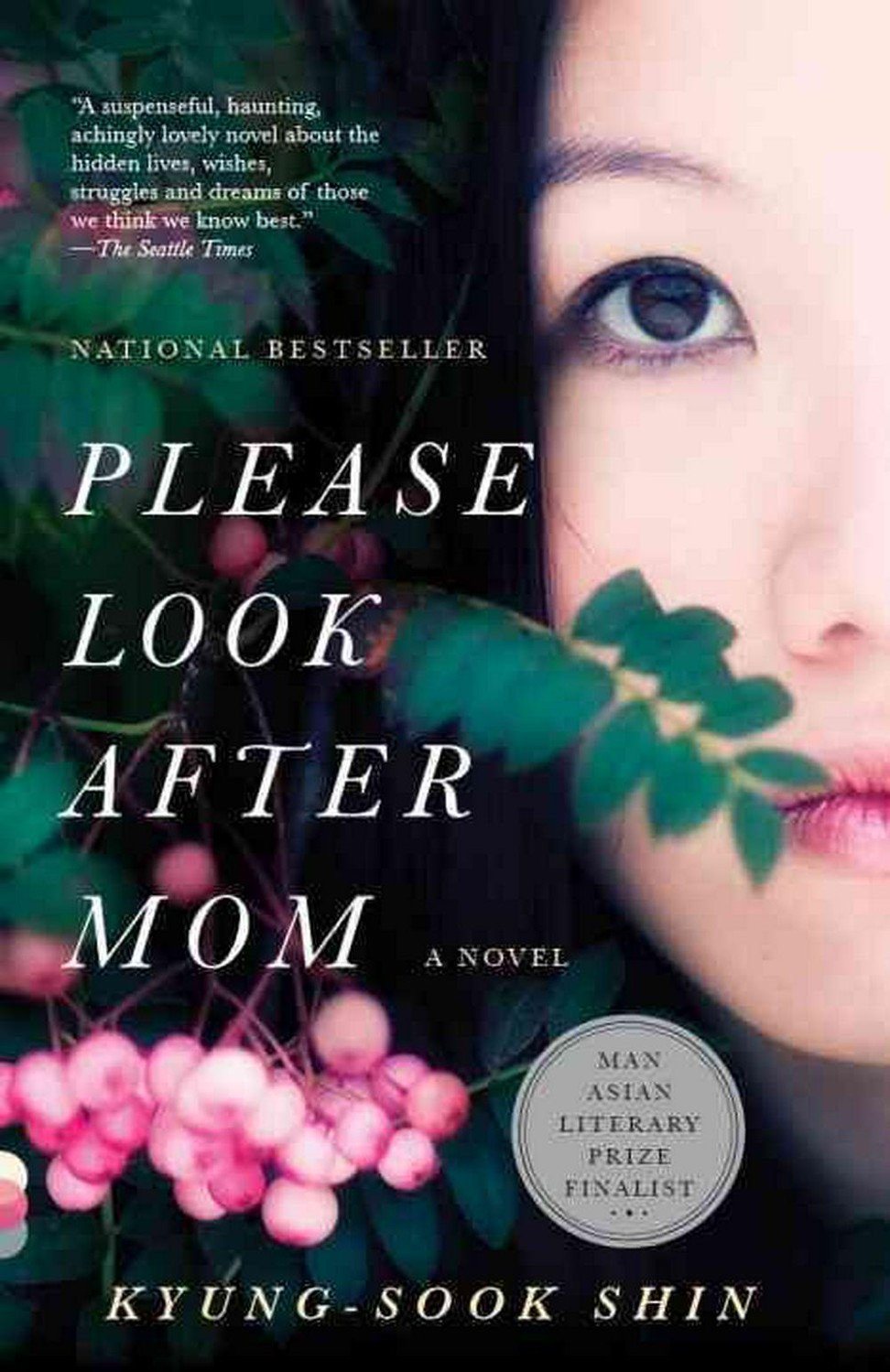

The Court Dancer, the latest novel by Man Asian Literary Prize winner Shin Kyung-sook, is likely to be read in several different ways. The first, and in some ways the most commercial, is as East-West romantic period fiction in the tradition of, say, Alessandro Baricco’s Silk or any number of English-language examples.

In the late 1880s, at a time of growing international threat to the Joseon dynasty, Yi Jin, a court lady, confidante to the queen and accomplished dancer, attracts the eye of the newly arrived French legate Victor Collin de Plancy, just as the queen starts to worry that Jin’s beauty might also catch the eye of the King. Jin has, fortunately or coincidentally, been taught French by a French missionary.

More substantially, Jin finds herself attracted to Victor’s library.

Victor soon asks for her hand – Jin’s own feelings are ambiguous and remain so, but has little choice in the end – and he is permitted to take her back to France. There, her beauty and fluency in French create a sensation; she impresses real-life author Guy de Maupassant when she reads his work at a gathering at the fashionable Le Bon Marché, and helps translate some of the first Korean literature into French. But she’s a fish out of water, and Victor takes her back to Korea, where she finds she no longer fits either.

The Court Dancer is, according to the blurb, based on a “remarkable true story”. Victor Émile Marie Joseph Collin de Plancy was the actual legate to the Korean court. And the story is based on an account co-authored by de Plancy’s successor, Hippolyte Frandin, about a Korean dancer given to a diplomat as a “gift”.

The dancer was named Li-Chin, the young diplomat in question was evidently Collin de Plancy; in En Corée, he takes her to Paris and then to Morocco. This intriguing story, alas, is otherwise unconfirmed. One would have thought that a French diplomat squiring an exotic Korean beauty around Paris would have attracted notice.

The illusion of The Court Dancer being a mainstream English-language novel is partly due to the fluent translation by Anton Hur. (A little too fluent at times, for Hur is taken with using “gift” as a verb which, whatever one may think about this usage, is wrong for the time and tone; nor would French aristocrats carry the title “Lord”.)

Adding in an important role for a benign Catholic missionary and later bishop is the sort of thing a writer might do to add more points of contact for Western readers, but then again, Christianity is important in contemporary Korea.

Of course, The Court Dancer is also distinguished by the Western protagonist being French rather than British or American, which adds certain je ne sais quoi to the narrative. Jin is probably grateful that her introduction to Western cuisine comes via coq au vin and mille-feuilles rather than battered cod and beer.

And Korea and Korean history are considerably less well-known than that of Japan and China, where such novels are more usually set. At some level, it is all familiar – silks, peonies, palanquins, palace intrigue and so on – but Shin includes considerable attention-grabbing detail, including the machinations of the late Qing dynasty. The presentation of China as a robust meddler in the Korean court and overseer of its foreign relations belies the normal narrative of a China succumbing to Western imperialism.

There are places where Shin’s Asian colours show, and not just in the detailed descriptions of Korean court life. On a visit to the Louvre, Jin asks why the Greek statues are in Paris rather than back in the Aegean.

She goes on to note that some important Korean books – seized by a French military expedition – are in French libraries, and questions Victor’s penchant for collecting Korean objects-d’art. These perhaps anachronistic political musings turn personal when she asks whether she might herself be just another piece of porcelain: “People here look at me like they look at the things you’ve collected, Victor.”

None of this quite blossoms into either feminism or true anti-imperialism. In addition to having a soft spot for French literature, culture and personal freedoms, Jin cannot escape her own fidelity to tradition. In finding herself, and finally gaining control over her destiny, she loses everything and anyone. Like a preserved plum, The Court Dancer is bittersweet throughout.