Live-action Ghost in the Shell remake feels like a blast from recent past

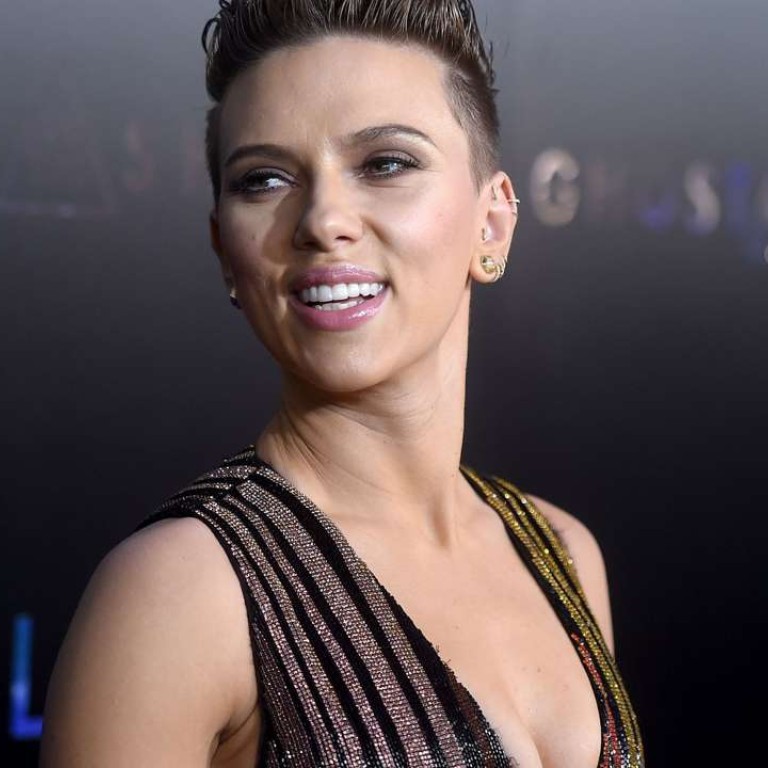

The casting of Scarlett Johansson in lead role as The Major has been derided, but this Hollywood version of Mamoru Oshii’s classic 1995 anime film also looks dated after a long lag in production

In movies, as in life, timing isn’t everything. It’s the only thing.

Consider the strange fate of Ghost in the Shell, the long-awaited live-action adaptation of the 1995 anime film by Mamoru Oshii. When Steven Spielberg announced in 2008 that DreamWorks had acquired the property, it looked like a stroke of genius: Ghost in the Shell had attained near-legendary status in the decade after its release, worshipped by fans for its artistry, its ineffable blend of fantasy and realism, and its noirish undertones of tech-savvy paranoia.

But the film took longer than expected to be developed and produced and what once looked prescient and even revolutionary feels as if it’s been dramatically outpaced both by movies and off-screen life.

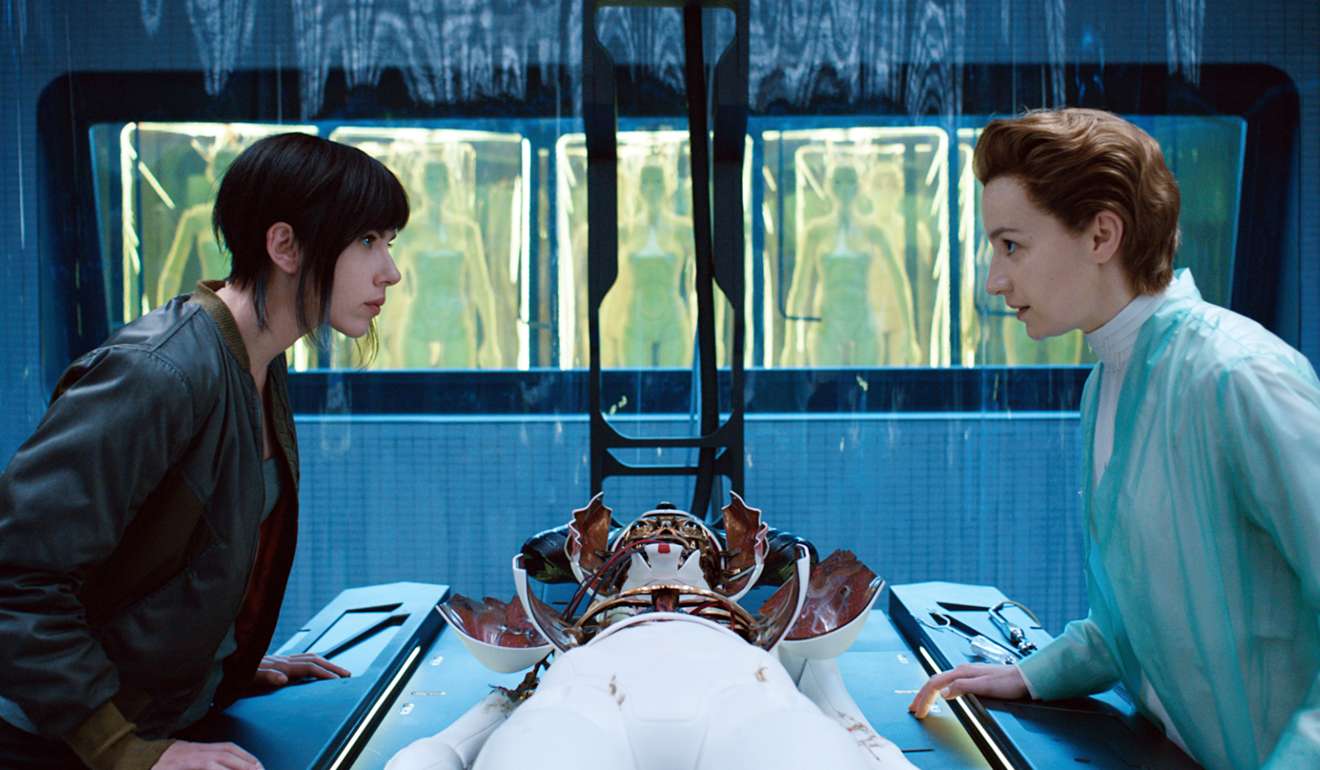

In a way, the 2017 version of Ghost in the Shell, which has been directed with respect and lavish visual style by Rupert Sanders, is the victim of its antecedent’s success.

Among the most ardent admirers of Oshii’s visionary movie – about a female robot with a human soul who fights cyberterrorism in a 21st-century city resembling Hong Kong – were the Wachowski siblings, who artfully borrowed and sometimes outright stole elements of Ghost in the Shell for their own revolutionary sci-fi thriller, The Matrix. Viewers can see similar influences in everything from Steven Spielberg’s A.I. and Minority Report to Christopher Nolan’s Inception and the 2014 fem-bot drama Ex Machina.

The original Ghost in the Shell’s cool factor – its noirish urban atmosphere, the visual slippage between the human form and technology, the beautiful, often startling depictions of physical transformation – has now been appropriated so often that it can’t help but feel derivative when Sanders does it, even though he’s arguably going back to the source for his inspiration.

From the Wachowskis’ anime-inspired (and arguably pretty dreadful) Speed Racer, the art form has progressed all the way to The Curious Case of Benjamin Button and last year’s fabulous part-live action, part-computerised reimagining of The Jungle Book.

When it was released in 1995, Ghost in the Shell was far from the first movie to explore themes of technological anxiety and existential dread; both Blade Runner and RoboCop, two groundbreaking sci-fi movies in their own right, had come out years earlier.

Still, a self-possessed, physically brave female crime fighter battling an unknown avatar of cyberterrorism feels eerily predictive at a time when anonymous hackers have played havoc with everything from nuclear reactors and financial systems to presidential elections. What once carried the shock of the dimly possible can’t hope to match the shock of what’s probable on any given day’s front page.

Interestingly, Oshii himself has blessed the casting of Johansson, noting that the “shell” into which her character’s brain is placed needn’t match her internal “ghost”. (“The Major is a cyborg and her physical form is an entirely assumed one,” he wrote in an email to the gaming website IGN.) Reportedly, Japanese fans of the first film are similarly unfazed, having expected all along for the Hollywood adaptation to feature a big star.

The bitter truth, of course, is that – so far, at least – no actress of Asian descent qualifies as a “big star”, at least in financiers’ opinions. As Rebecca Sun recently reflected in the Hollywood Reporter, after noting how Johansson grew into a name actress through progressively larger roles, “How does an Asian actor become famous enough to play an Asian character?”

That question will only take on more urgency as movie markets expand around the globe and audience expectations change in the US. Recent data shows that although the majority of moviegoers are Caucasian, they accounted for fewer ticket sales last year; the most significant increase in moviegoing occurred among those defined as “Asian/Other,” who purchased 14 per cent of the year’s movie tickets, even though they only represent 8 per cent of the population.

Admittedly, Johansson’s ethnically non-specific depiction of The Major in Ghost in the Shell isn’t nearly as distracting as, say, the offensive choice to cast Emma Stone as a part-Asian character in Aloha. Still, Ghost’s reliance on an increasingly unreliable casting model feels hopelessly at odds with a movie venerated for its forward-leaning themes and aesthetic.

With the star system itself looking more and more rickety, and streaming and virtual reality making revolutionary inroads into the ways we see and experience cinema, the 21st-century Ghost in the Shell is a good, often visually arresting, movie. But that might be its biggest problem. It’s missed its chance, not merely to re-enact the innovations of its predecessor, but also to redefine them for a new generation.

Instead of feeling like it’s been beamed from a distant future, it plays like an artefact of a rapidly receding past.