Indonesian TV censorship: cartoons cut, athletes blurred as conservative Islam asserts itself and broadcasters fear sanctions

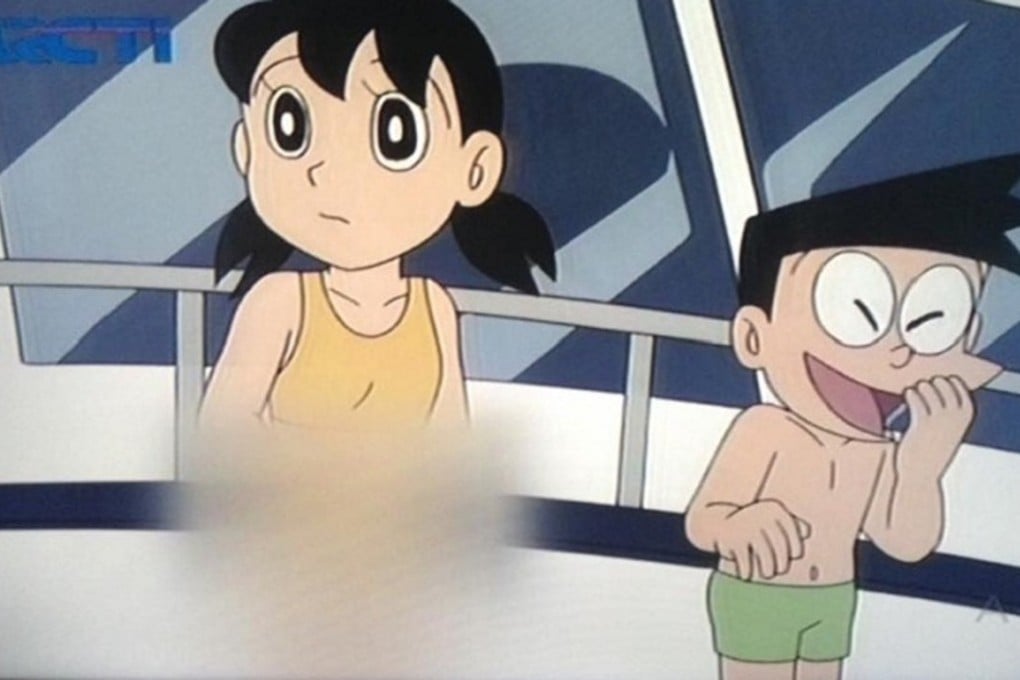

Kissing scenes in Shaun the Sheep, swimsuits in Doraemon, even a female athlete on CNN – Indonesian TV censors are in overdrive, and internet streaming could be next. Some parents, though, welcome the oversight

It may not have been so unusual to hear earlier this year that the Indonesian Broadcasting Commission (KPI) had issued a warning letter to a television station for airing a programme featuring a kissing scene.

It was not, though, part of a sexually charged, passionate embrace. The offending scene appeared in an episode of Shaun the Sheep, the British animated children’s series and spin-off of the popular Wallace and Gromit franchise.

Headbangers in hijabs: inside Indonesia’s heavy metal scene

The watchdog ruled that the programme, which aired in July, violated Article 14 on child protection and Article 16 on the limitation of sexual content in the Broadcasting Code of Conduct and Broadcasting Standards.

KPI spokesman Andi Andrianto told the South China Morning Post that the segment was inappropriate and unacceptable for a television programme aimed at young children. “The scene began with a ring falling between a woman’s breasts, and then the couple stared at each other and kissed,” he explains.

As the country’s supervisory body overseeing television and radio broadcasters, the KPI will file warning letters and demand that broadcasters stop showing content deemed to be in violation of the code of conduct and broadcasting standards. It does not issue fines. Instead, the KPI has the authority to revoke a company’s broadcasting permit after issuing a third warning letter. It is the responsibility of broadcasters to censor the content they air.

However, the situation has led to accusations of overzealous censorship among television stations, of which there have been a number of memorable cases in recent years involving children’s cartoons.