Indonesian films often show ethnic Chinese in a bad light – but filmmakers are turning their backs on old stereotypes

Chinese characters in Indonesian cinema either had exaggerated accents, or were corrupt businessmen exploiting workers in a whirl of lion dances and firecrackers. Film directors like Sidi Saleh now want to give a true portrayal

Indonesian film director and cinematographer Sidi Saleh is no stranger to Glodok, the Jakarta neighbourhood colloquially known as Chinatown. When he was younger, he would spend weekends with relatives who lived in the adjacent Jembatan Lima district.

Although Saleh, 38, is not of Chinese descent, the filmmaker became familiar with the everyday lives of Chinatown residents on his strolls through the area.

Film review: Beyond Skyline – alien invasion sequel, featuring monster fights and an Indonesian action star, is ridiculous but fun

He may have been drawing on those experiences as he wrote and directed his first full-length feature film, Pai Kau. Its box office release, on February 8, was eight days before the Lunar New Year festival.

Inspired by the works of Hong Kong director Johnnie To Kei-fung and mainland Chinese auteur Jia Zhangke, Pai Kau – a reference to the Chinese domino gambling game pai gow – has all the makings of a typical action flick. “It’s just like one of those Hong Kong movies,” Saleh says, referring to its gangsters, love triangle and lots of violence.

The film also features a cast that “is comprised almost 100 per cent of Chinese-Indonesian actors”, Saleh says. However, there are none of the usual stereotypes used in depictions of ethnic Chinese communities in Indonesian cinema – no lion dances, firecrackers or exaggerated accents – and the wedding scene involves a Catholic ceremony, not Buddhist.

Pai Kau is a rare break from the usual representation of ethnic Chinese citizens in Indonesian cinema. Representation of the ethnic Chinese minority has more often than not been tied to identity politics. That is according to Charlotte Setijadi, author of the upcoming book Memories of Unbelonging: Collective Trauma and Chinese Identity Politics in Indonesia, and Krishna Sen, a consultant for a number of international human rights agencies in Indonesia and a professor at University of Western Australia’s School of Social Sciences. Sen penned the 1994 book Indonesian Cinema: Framing the New Order.

During former president Suharto’s repressive New Order regime (1967-98), for example, Setijadi has written, “Chinese-Indonesian actors were mostly stuck playing comical Chinese characters with heavily accented Indonesian, or corrupt businessmen who exploited the pribumi workers”.

Pribumi was a word coined during the Dutch colonial era (1800-1949) to describe the indigenous population and is rarely used today because it provokes anger and division along racial lines.

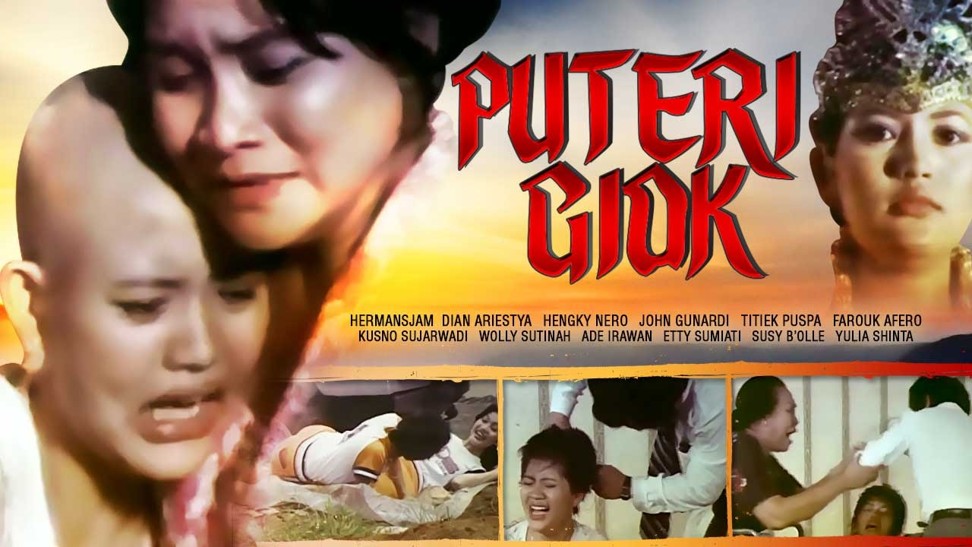

The 1980 release Putri Giok (Beautiful Giok), a love story between an indigenous and a Chinese Indonesian, is one example of a film that, according to Sen, “projected the official New Order version of both the ‘Chinese problem’ and its solution through a very particular kind of ‘assimilation’”. Erasing Chinese identity was key to the struggle for national belonging under Suharto. Chinese Indonesians were expected to mask their cultural and ideological differences, and doing so was regarded as a virtue.

It had not always been this way. The first domestically made films were produced in the 1920s under Dutch colonial rule, when a generation of ethnic Chinese found themselves employed in the local film industry. Among them were Joshua, Othniel and Nelson Wong, otherwise known as the Wong Brothers, who founded the production company Halimoen Film.

Nelson directed the prominent 1928 film Lily van Java (Lily of Java), about a young woman in love who is forced by her father to marry another man. In 1937, Othniel and Joshua were the cinematographers for Terang Boelan (Full Moon), on a similar theme: two lovers elope after the woman is forced to marry an opium dealer.

The Chinese remained big film industry players throughout the 1930s in what was then called the Dutch East Indies, not just as directors, but also financial backers.

Prominent among them was the prolific The Teng Chun, who produced and directed 11 of the 13 films made on Java island from 1933 to 1937. These included the popular Boenga Roos dari Tjikembang (Rose from Cikembang, 1931) and Gadis Jang Terdjoeal (Jang Terkjoeal Girl, 1937). After the Japanese invaded the country in 1942, however, his studio was closed down by the occupying forces, and Chinese presence was virtually erased from the industry.

China’s golden-age of science fiction pushes new boundaries at Hong Kong conference

According to David Hanan, who wrote the 2017 book Cultural Specificity in Indonesian Film, the Japanese shut down all but one film studio, and “a small number of Indonesian directors – those regarded by the Japanese as connected with the independence movement – were invited to direct propaganda films”.

It was only after Indonesia declared independence in 1945 – four years before the decree was recognised by the United Nations – that a concept of national cinema slowly, but bravely, emerged. Indigenous directors including D. Djajakusuma and Usmar Ismail began making films depicting the aftermath of the second world war and efforts to rebuild the country.

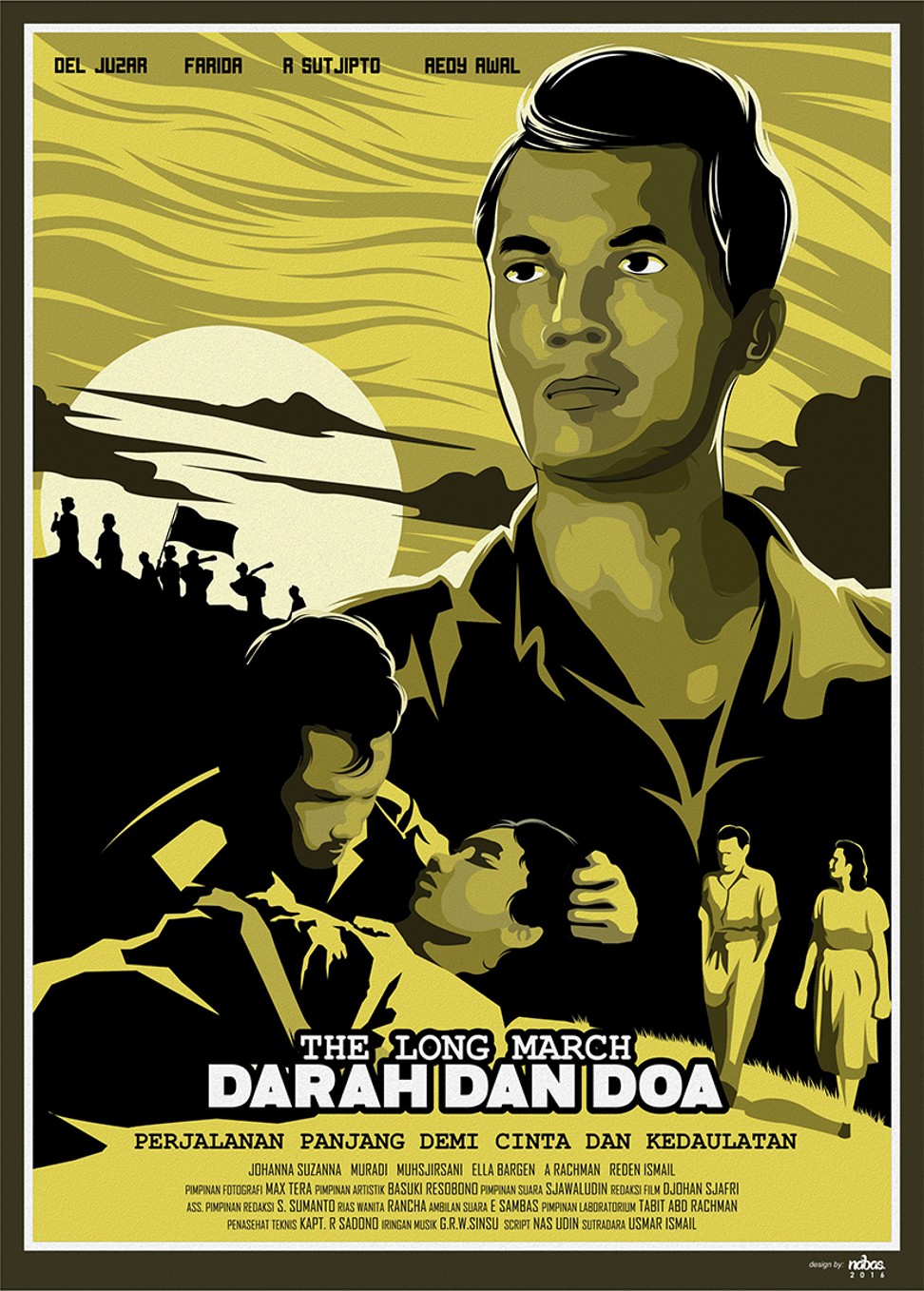

Usmar’s 1950 film Darah dan Doa (The Long March) is widely regarded as the first truly “Indonesian” film. The date shooting began, March 30, was officially declared National Film Day by former president B.J. Habibie, who became the country’s third president in 1998 after the fall of Suharto.

“Our cinema has a strong bias towards the national struggle for freedom,” says Adrian Jonathan Pasaribu, co-founder and editor of the Indonesia-based film studies and criticism website Cinema Poetica. “Starting from 1945, there were marked lines between [people] who are from here and [those] who aren’t,” he says.

This cultural bias is one of the reasons Pasaribu gives for the fact that Chinese names have been forgotten in the history of Indonesian cinema. The other is poor archiving that has led to the loss of many early films.

Starting from 1945, there were marked lines between [people] who are from here and [those] who aren’t

Hanan echoes this notion. “In fact, of the 114 or so films known to have been made in the pre-1950 period, less than a dozen are known to survive,” he writes.

As part of Suharto’s assimilation credo, the 1961 policy that forced Chinese nationals to replace their names with Indonesian-sounding ones also played a role in this act of national amnesia.

Sen notes that Chinese-Indonesian filmmakers were still involved in the industry in the 1950s, but argues that “Chinese-Indonesian writers, directors and technicians had become a small minority by the 1960s, and even that relatively small presence was hidden under adopted names and identities”.

Examples are Teguh Karya (Steve Liem Tjoan Hok), Wim Umboh (Liem Yan Yung) and Tandu Honggonegoro (Tan Sing Hwat).

A search for identity still looms large in the work of Chinese-Indonesian filmmakers today, in a country that has more often than not regarded them as “others”. The independently produced 2008 film Babi Buta yang Ingin Terbang (The Blind Pig Who Wants to Fly) is remarkable for depicting the lonesome subjectiveness of Chinese Indonesians without resorting to exoticising the characters.

Even today, the idea of a film that features a nearly 100 per cent Chinese Indonesian cast verges on radical.

“I was walking around in the Glodok area and I just approached an old women whom I thought would be great in the movie. Some of them were frightened – they took five steps back. But I’m on Wikipedia, so I explained to them that I’m a film director,” Saleh says.

Saleh’s casting process wasn’t the only taxing aspect. Together with producers Tekun Ji, Dennis Sutanto and Irina Chiu (all ethnic Chinese), the team debated the importance of the wedding scene, which was ultimately filmed in a Catholic church.

The lives of the Chinese Indonesians in Jakarta today, Saleh says, aren’t always defined by traditional chinoiserie. “Not everything about the Chinese is red, has to feature a lion dance, red lanterns, or whatever,” he says.

Saleh and Sutanto agree that identity politics are not the point of Pai Kau, but they went to great lengths to ensure the film’s authenticity, even hiring a wedding consultant who usually handles Chinese-Indonesian weddings.

The director admits that he spent no time in Glodok during the outbreak of violence and riots targeting Chinese-Indonesian in 1998. As a non-Chinese, he contends that invoking Chinese-Indonesian identity might still seem sensitive.

Crazy Rich Asians trailer hits screens – and it’s glorious

But Pai Kau holds a deeper meaning for the country’s diverse cinema. Saleh realises this, even if it wasn’t his intention. “Seeing a film where most of the Chinese people speak Indonesian, it goes to show that they’re just a part of us … as they’ve always been,” he says.