The Velvets vs The Beatles: 50 years on from the release of two landmark albums and their battle for the soul of rock ’n’ roll

In 1967 it was Sgt Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band, the Fab Four’s slick studio album, that was hyped as groundbreaking, but The Velvet Underground’s raw debut record was to prove far more influential

What a difference a half-century can make, especially when considering the impact of two landmark albums released only a few months apart 50 years ago. That they are even being considered in the same sentence today would’ve seemed preposterous in 1967. And the same is true now, except the albums have traded positions.

In the months leading up to the release of Sgt Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band, The Beatles knew that every word and sound they were recording would be scrutinised and likely celebrated, and they set their sights on the centre of a youth culture that hung not just on their every song, but the way they dressed and styled their hair, what they said and how they said it.

The mainstream media would be primed as well – established publications such as Time and The New York Times praised the grown-up sophistication of Sgt Pepper when it was released on June 1, 1967. It was hailed as a “decisive moment in western civilisation” and its artistic reach was compared to that of George Gershwin and T.S. Eliot. Years later, critic Langdon Winner amplified the hype in The Rolling Stone Illustrated History of Rock’n’Roll: “The closest western civilisation has come to unity since the Congress of Vienna in 1815 was the week the Sgt Pepper album was released.”

The Velvet Underground, on the other hand, clearly knew that with its debut, The Velvet Underground and Nico, released on March 12, 1967, they were making an album that failed almost every test of pop culture currency. Band members were seen as vile pornographers by those who superficially scanned and demeaned their risqué subject matter: drugs, decadence, deviant sex.

Their record was banned from some stores, ignored by radio programmers and shunned by some publications, which refused to run ads announcing its arrival. The record sank off the charts the same week as Sgt Pepper was ushering in the “Summer of Love”. Years later, the Velvets’ John Cale shrugged when asked if the band was disappointed by the response. “There was a theory of stubbornness at work within the band. We didn’t care what anyone thought.”

Now the “Summer of Love” feels like an artefact, and the Velvets’ vision of a landscape in which primitive rock’n’roll merged with literary and avant-garde aesthetics feels fresher than ever. Sgt Pepper was clearly a product of its era, a work that followed up superior Beatles albums such as Rubber Soul and, especially, Revolver.

The studio experimentation that so dazzled contemporaries in 1967 was already in full bloom a year earlier on Revolver, thanks to such visionary songs as Tomorrow Never Knows. And the songwriting on Revolver was extraordinary – the melancholy beauty of Here There and Everywhere, the violent cool of Taxman, the jangling pop perfection of And Your Bird Can Sing – a standard that its more celebrated follow-up could not match.

Sgt Pepper offered the groundbreaking A Day in the Life and the psychedelic visions of Lucy in the Sky with Diamonds, but much of the rest comes off as slight and overly clever and self-conscious. Songs such as the dance hall homage When I’m 64 or the mash note to a meter maid, Lovely Rita, sound of a piece with the bubblegum of British contemporaries such as Herman’s Hermits or Gerry and the Pacemakers rather than of the group that released the double-sided single Strawberry Fields/Penny Lane only months earlier.

Expectations were ridiculously inflated for Sgt Pepper. The album was crafted over 700 hours in the studio – a huge extravagance by the era’s standards (the Beatles spent less than 10 hours making their debut album four years earlier). And it arrived after the Beatles had proclaimed they would no longer tour to focus on recording.

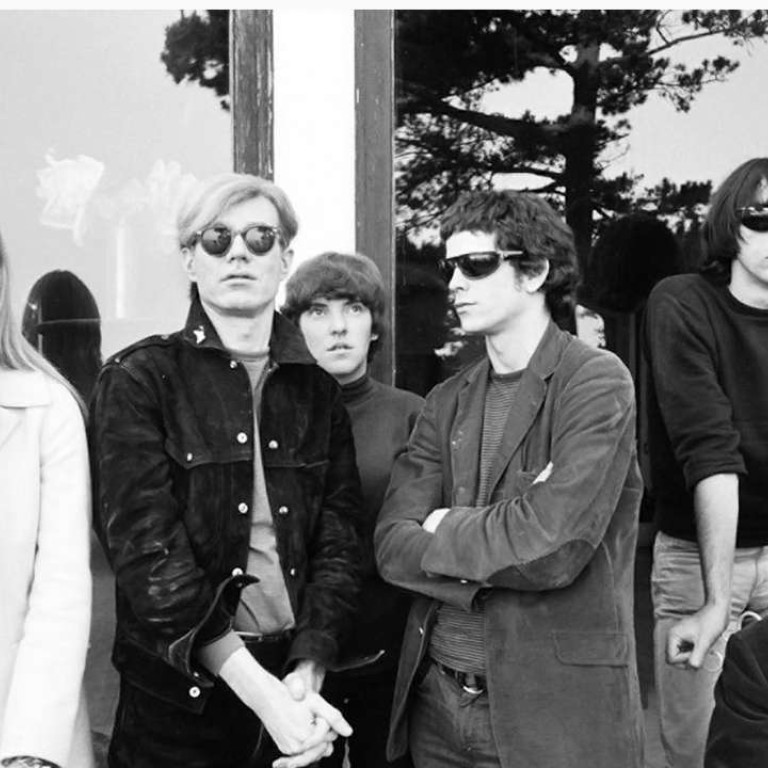

In contrast, The Velvet Underground & Nico was initially viewed as the work of a dicey-looking cult band cooked up by pop-art icon Andy Warhol, ostensibly the album’s “producer”. Warhol’s role in the band was minimal. He helped foster some of the theatrical elements in the quartet’s “Exploding Plastic Inevitable” shows, designed the famed banana album art and brought in model-turned-vocalist Nico.

Primarily, he provided a kind of insulation from corporate record-label interference. He enabled Lou Reed, John Cale, Sterling Morrison and Maureen Tucker to chase their singular vision, a true melding of high-art ambition and raw rock ‘n’ roll, flavoured with avant garde, classical and world music elements – only without the recording budget of the Beatles.

The Velvets’ songs provoked outrage. Heroin chronicled a junkie’s habit in novelistic detail with an ebb-and-flow arrangement built on Tucker’s tribal drumming, Cale’s scraping viola and Reed’s deadpan vocal. It offered no judgments or pronouncements, only a point of a view from a voice not often heard in popular music. Venus in Furs took a mystical, droning plunge into the world of sadomasochism as depicted in the work of Austrian novelist Leopold von Sacher-Masoch.

These were not particularly comforting songs, nor were they intended to be. The Velvets saw the ’60s as a grand marketing scam, and they were an opposition party of four, wary of youth culture movements and “flower power” sloganeering. Over time, their music – abrasive yet beautiful, poetic yet punishing – felt strangely accessible to kids picking up their guitars around the world. It would resonate later in the music of everyone from the Sex Pistols and the Talking Heads to R.E.M. and the Strokes.

Yet the Velvets’ mission was a solitary one in 1967, a time when almost every other band aspiring to break into the pop charts wanted to be The Beatles. The Velvets believed in rock’n’roll, yet wanted to push it forwards on their own uncompromising and widely derided terms. Reed saw it as music that could be as sustaining and artistically ambitious as a great novel or movie.

The Velvet Underground and Nico saw the world with a ruthless clarity that went beyond mere teen-dream escapism. Next to it, Sgt Pepper – despite its kaleidoscopic sound and studio achievements – sounds almost quaint.