China’s rust belt starting to shine with new economy firms, but the prosperous south still leads the way

- The provinces of Liaoning, Jilin and Heilongjiang began China’s industrialisation in the 1950s, but they now must modernise to boost the economy

- State-owned enterprises slowing beginning to work with start-ups and research and development institutes to modernise their technology

The northeast rust belt, once the pride and birthplace of China’s industrial development, is in its biggest economic slump as it struggles to shake off a deep-rooted planned economic mindset and dwindling resources, and a brain drain to regain competitiveness. This is the fourth article of a five-part series that looks at whether the new economy can buffer the downturn in traditional rust belt industries.

In the four years since it was established, automated flight control system developer Woozoom has grown into a 150 million yuan (US$22 million) start-up that is not short of suitors seeking to invest.

Based in the Liaoning provincial capital of Shenyang, the company is among a new breed expected to inject new blood into China’s struggling northeast rust belt, which could give ageing industries and state-owned enterprises (SOEs) a jolt, and over time help revive their competitiveness.

While these young firms are a long way from becoming an integral part of the region’s economic mainstream, they are slowly infiltrating a regional economy predominated by the country’s biggest industrial SOEs. But despite this, the development gap with the rest of the country has continued to widen, resulting in steady economic decline for the region.

Compounding the problem are inadequate market-oriented industrial policies and a poor business environment compared with China’s more prosperous southern and eastern regions, said Woozoom’s founder Su Wenbo.

“But the past two years have seen improvement,” Su said. “The [local] science and technology bureau has provided hi-tech firms with supporting policies. And their approach is also more holistic. Previous policies weren’t realistically usable, but these ones are now applicable.”

Reviving the northeast means confronting a myriad of complex issues tied to generations of autocratic planning and political meddling, which analysts and entrepreneurs in the region believe will require a concerted effort over the long term by central and local governments companies and institutions like universities and research and development (R&D) facilities.

China’s northeast rust belt, which is made up of the provinces of Liaoning, Jilin and Heilongjiang, is where the country’s industrialisation began in the 1950s. It was the birthplace of heavy industries like aircraft and military equipment manufacturing and mining, represented by SOE heavyweights including Shenyang Aircraft and Shenyang Machine Tool that guard what Beijing described as the nation’s economic lifeblood and security.

Their approach is also more holistic. Previous policies weren’t realistically usable, but these ones are now applicable

That mindset of top-down control is so deeply rooted that it has stalled the structural reforms needed for the region to evolve into a market economy, and blunted companies’ sensitivity to market trends, including those in less traditional sectors including services and retail.

The three provinces’ combined services industry, valued at 897 billion yuan (US$132 billion) in revenue, is less than a third of the size of southern Guangdong province’s 3 trillion yuan (US$443 billion) service sector. This has left the region struggling to implement Beijing’s push to bolster domestic consumption to buffer the economic slowdown caused by the trade war with the United States.

The economies of Liaoning, Jilin and Heilongjiang, which grew last year between 4.5 to 5.7 per cent, are at the top of the list of Chinese provinces with the slowest growth in 2018, well behind the national rate of 6.6 per cent. The provinces’ SOEs have also chalked up more than 2 trillion yuan in debt, a large portion of their 2.7 trillion yuan in assets.

To their credit, these firms now realise the urgent need to raise their game as rapid technological advancement continues to disrupt traditional industries, sending companies reeling.

Sandy Zhang, founder and executive director of Shenyang-based Miku Entrepreneur Service Centre, a central government-endorsed business incubator, said SOEs were increasingly collaborating with start-ups and R&D institutes to upgrade their operations with modern technologies.

“These old industrial [manufacturing] SOEs are badly lacking in R&D capabilities. They are also structurally backward, which weakens their ability to innovate,” said Zhang, whose platform aims to help existing companies in the northeast innovate and start-ups to expand and grow into viable businesses. It currently serves a network of 4,000 start-ups.

Although Zhang dismissed suggestions that the strength of northeastern start-ups pales in comparison to those in the south, the reality is the region is not the first choice for venture capitalists or investors.

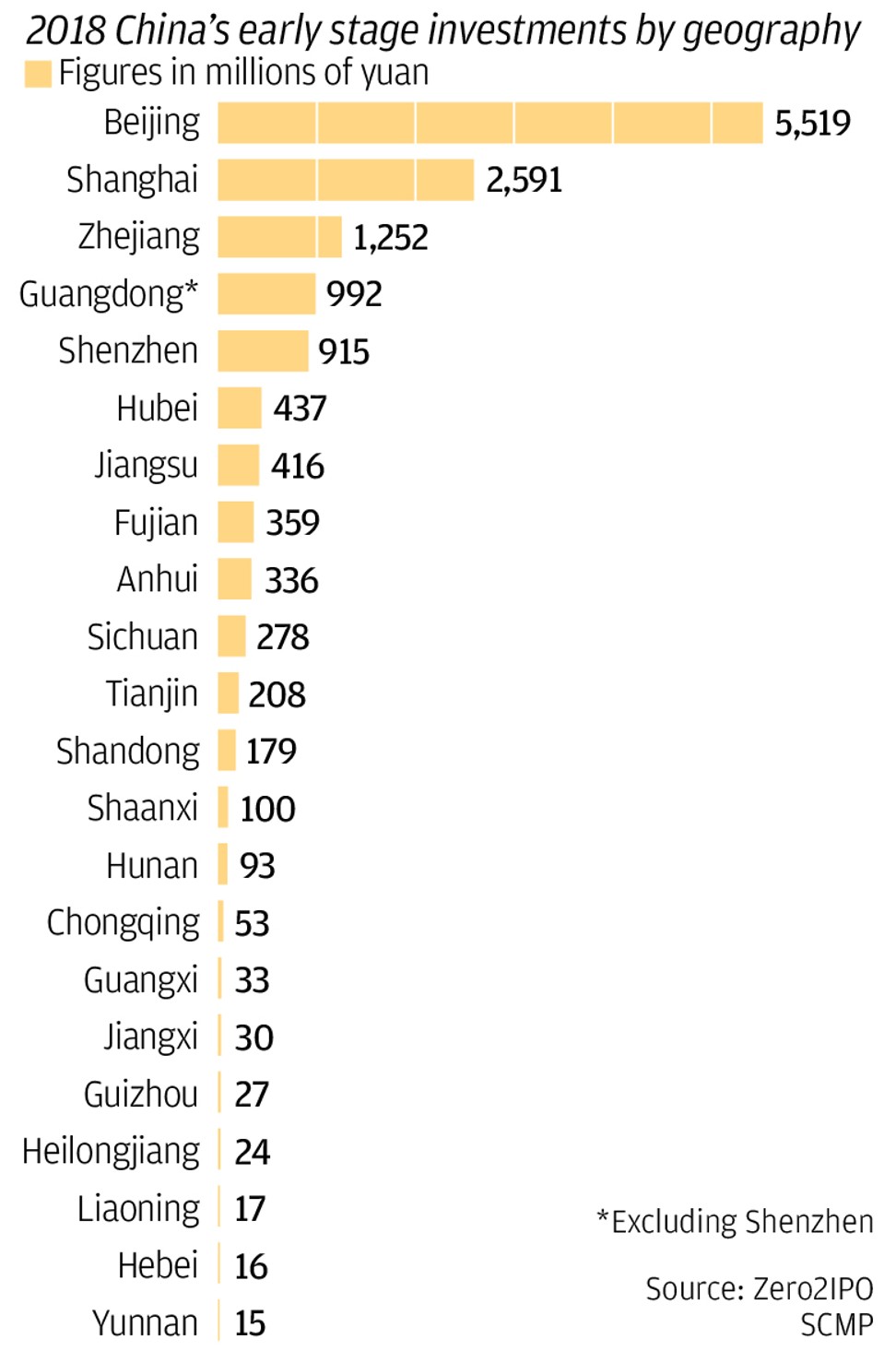

By scale and value, it remains far behind the likes of Beijing, Shanghai and the eastern Zhejiang province, which have the biggest technology start-ups and unicorns, which are firms valued at US$1 billion or more, meaning much-needed capital is not flowing into the northeast where it is most needed.

Nearly 40 per cent, or 5.5 billion yuan (US$811 million), of the country’s 14.2 billion yuan in early stage investment flowed into Beijing’s 650 projects last year. By contrast, a mere 0.1 per cent, or 17 million yuan (US$2.5 million), went into Liaoning for four projects, according to the Chinese consultancy firm Zero2IPO.

Woozoom’s Su said the local Liaoning government has initiated a programme of start-up funding in which it contributes a third to two-thirds of the capital, but more needs to come from private investors, especially for early-stage R&D where uncertainty is most prevalent.

“But private capital transactions are not at all active [in the northeast],” he said.

The weak inflows reflect investor caution towards the region, focused on the overbearing role of the state, coupled with local protectionist policies and inconsistent governance.

Fluctuating foreign direct investment (FDI) into the region is a case in point. FDI into Liaoning – the biggest economy of the three provinces – fell 8.2 per cent last year, bucking the overall strong increase across China.

For private firms and start-ups that are asset light with little or no collateral, the difficulty in raising capital is also crimped by banks’ strong preference to lend to SOEs that have tangible assets and are seen as having implicit government backing.

In its position paper, the European Chamber of Commerce in Shenyang underscored the need for a level playing field for small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) that are the primary drivers of innovation.

“If Shenyang is to increase its capacity for innovation it needs to take measures to create a more SME-friendly environment,” it said.

Private SMEs in the rest of China have powered phenomenal growth over the past four decades, and now account for 60 per cent of the national gross domestic product and 80 per cent of urban jobs. In contrast, only six out of the top 500 private firms in the All-China Federation of Industry and Commerce’s index for 2018 were from Liaoning.

Companies, especially state-owned entities, have been unable to draw on new resources like capital and talent to transform because of their inflexible structures and systems, as well as legacy baggage, said Qu Daokui, president of the Shenyang-based Siasun Robot and Automation, China’s largest robotics manufacturer.

“The development of new resources, a new economy and new technologies are comparatively slower here. The reason for the slower pace is because of a lack in talent, capital and investment,” he said.

Of these, the dearth of talent has become a severe problem with a “bigger impact”, Qu said, as while the region has not only failed to attract new resources, people are also leaving in record numbers amid the economic slump.

That said, local entrepreneurs remain optimistic, with a rebound in growth is in sight. In particular, there has been a shift in local officials’ mindsets towards less interference and more support for reforms to improve the business climate, in line with the national push for promote innovation and entrepreneurship by cutting bureaucratic inefficiency and introducing policies to help companies.

As the region’s economic hub, Shenyang is building a regional technology platform with the 17,000 hectare (42,000 acres) Shenyang Hi-tech District, where Siasun and Miku are both based.

Miku’s Zhang said her platform is focusing on high-end automated manufacturing and the medical sector, leveraging big data and artificial intelligence to build on Liaoning’s traditional manufacturing and medical industry strengths. The incubator has sought out hi-tech domestic and foreign collaborators and projects that will benefit northeastern companies.

“Shenyang companies have also acquired various small firms specialising in different technologies … approaching and starting to make the changes partially and gradually,” she said.

For example, property developer Shenyang Yuanda Enterprise Group has expanded into intelligent construction and agriculture through a foreign joint venture on micro-irrigation technology that would help Chinese farms upgrade and raise efficiency.

To its benefit, the region has some of the country’s top research and teaching universities as well as R&D institutions. In 2004, Shenzhen-listed Siasun was created from the Institute of Automation of the government-backed Chinese Academy of Sciences, which still holds a 25 per cent stake.

Neusoft, China’s largest software outsourcing provider established by former Northeastern University professor Liu Jiren, is another.

“The northeast has no short of science and technology talent,” said Su, who started Woozoom with fellow researchers from the Chinese Academy of Sciences.

As far as start-ups and new economy firms go, Miku’s Zhang does not expect them to be strong enough to be a major growth driver in the short term.

“Traditional manufacturing will continue to be the [economic] mainstay [of the regional economy],” Zhang said.

The incubator is mulling a new capital-raising scheme to address the difficulty faced by start-ups to secure funds. The mechanism will be based on metrics to gauge a firms’ credit worthiness that banks could use in assessing loan applications, she said.

“The new economy sector will grow rapidly in the next three to five years,” she predicted.

In that same period, Woozoom aims to launch 16 new products, including some targeted at the agricultural industry.

“There are more than 800 million farmers,” said Su. “Upgrading agricultural efficiency could result in more people returning to the countryside to help develop the rural areas.”

The final article of this five-part series looks the i mpact of brain drain on the outlook of China’s rust belt.