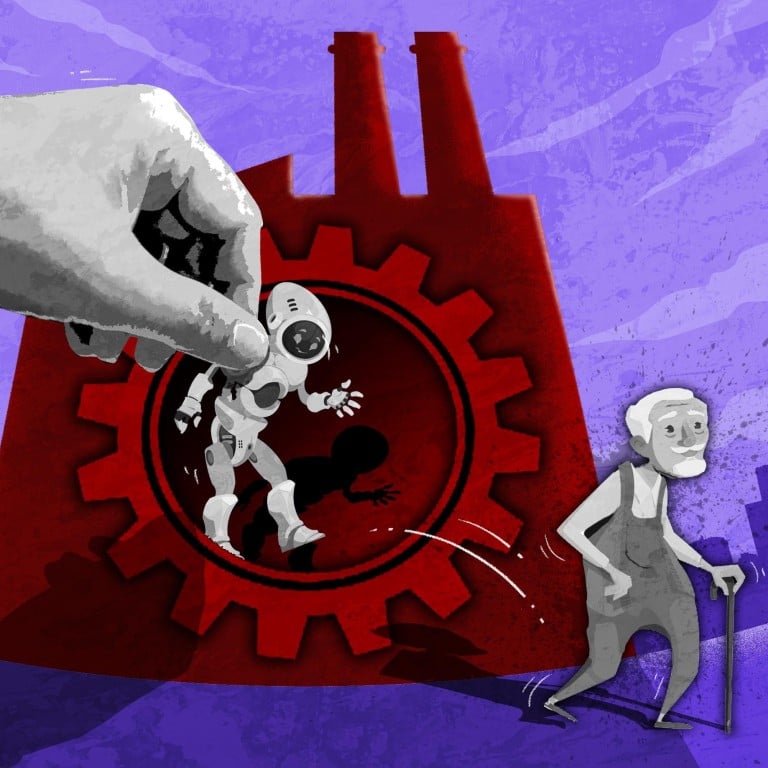

China steels itself for labour shortfalls, demographic decline with industrial robots

- As China looks for ways to cope with its shrinking labour force and ageing population, robotic manufacturing looms large as potential answer to both problems

- Gains in labour productivity and efficiency could create a ‘robot dividend’ that fills gaps created by a smaller working-age population

In textile factories across eastern China’s Yangtze River Delta, a remarkable change has taken place.

To the casual listener, shop floors once crowded with workers have become wholly alien environments. The formerly syncopated rhythms of human activity are now rigid, precise, almost machine-like – because that’s exactly what they are.

This traditionally labour-intensive sector has joined several others in making the transition to robotic production, replacing employees with highly specialised and automated equipment. Companies are doing so to keep labour costs steady and prepare for the inevitable contraction of the workforce as a proportion of the total population.

Plants with a yearly output of 300 million yuan (US$41 million) previously needed about 100 workers to maintain. Now most are largely unstaffed, requiring only four or five workers to keep up production.

Productivity gains have created huge scale and cost advantages

Robotic production is one way to consolidate the region’s industrial chains and protect against relocations to places with lower labour costs like Southeast Asia or parts of China that are further inland.

Textile factories in the delta, which includes Shanghai and the provinces of Jiangsu and Zhejiang, are some of the hardest hit by China’s recent population shifts.

“Automation of production lines has actually helped retain factories and complete industrial chains,” said Xue Ping, a textile furniture manufacturer and exporter in Zhejiang.

“Such factories will not move to Southeast Asia, because productivity gains have created huge scale and cost advantages currently unmatched by any other country.”

China has expanded its use of industrial robots as it aims to climb the industrial chain. Advanced technology and smart manufacturing, industry insiders and manufacturers said, is key to sidestepping geopolitical complications and coping with the demographic changes that are all but inevitable.

According to the country’s Ministry of Industry and Information Technology, China produced 281,515 units of industrial robots in the first eight months of 2023, up 2.3 per cent year on year, and had established nearly 8,000 digital factories and smart manufacturing plants by July.

The timing is fortuitous. China’s working-age population – those between 16 and 59 – fell to 875.6 million in 2022 from 896.4 million in 2019, while its population above 65 rose to 209.78 million last year from 176 million in 2019.

Total operational stock in China passed the 1.5 million-unit mark in 2022, with 290,000 units installed last year according to the International Federation of Robotics (IFR). This was more than half of industrial robots installed last year worldwide.

China is the only country to pass the 1.5-million-unit milestone, with 728,391 units operating in all of Europe and 452,217 in North America, IFR said. Adoption is being driven mainly by its automotive, machinery and electronics industries.

The country aims to double its 2020 robot density in the manufacturing sector by 2025 and deploy over 100 applications and solutions for the technology.

“Ageing is just one of the factors,” said Luo Jun, secretary general of the Asian Manufacturing Forum, a government think tank which advises authorities on smart manufacturing. “More importantly, it is the ever-expanding need for industrial transformation and upgrading which will lead to the growth rate of China’s industrial robots being first in the world and remaining so.”

Luo said putting robots in a leading role will allow China to maintain its robust industrial system as it competes with emerging markets seeking to challenge China’s status as the world’s factory.

“At the same time, we are seeing a number of emerging industries rising rapidly in China, such as new energy vehicles, lithium batteries and photovoltaics,” he said.

This advancement is increasing China’s place in the global manufacturing discourse, Luo added, which will promote the country’s new round of industrial upgrading.

China should not only consolidate its status as the world’s factory, but aim to become as advanced a manufacturing power as Germany and Japan, he said.

“At this stage, China’s manufacturing industry is still in the mid-range,” Luo said. “But in the future, China will enter late or post-industrialisation, and then will have more direct competition with Europe and the United States.”

The ‘robot dividend’ would make up more than half of the future labour shortage

It could also create additional jobs via boosting productivity and real income and spending levels, creating an additional 90 million jobs by 2037, the report estimated.

Dongguan has implemented 4,653 “machine-for-human” projects since September 2014 – mainly via large local enterprises – involving investment of more than 60 billion yuan (US$8.2 billion).

Upon completion of the projects, production line workers have been reduced by about 340,000, but the average yield rate of the involved enterprises has risen from 88.3 to 92.5 per cent.

The average yield on an investment is the sum of all interest, dividends or other income that the investment generates, divided by the age of the investment or the length of time the investor has held it.

Rise of the machines: China’s struggling industries embrace automation

Unit product costs also dropped by an average of 9.3 per cent, and labour productivity increased by an average of 3.7 times, according to official data.

“Even if China’s working-age population declines significantly,” Luo said, “it will still be enough to support the goal of becoming a manufacturing power.”

Some demographers, however, have cast doubt on the effects of automation to counter the ageing population.

“Automation helps upgrade manufacturing and the supply chain, but it does little to help domestic consumption and the ageing problem,” said independent demographer Huang Wenzheng.

In the long run, a shrinking population is more likely to lead to a relative decline in gross domestic product per capita and extraordinary talent, he added.

Perhaps predictably, manufacturers are more optimistic. As founder of Dongguan-based East Group, a leading integration solutions supplier in China for photovoltaic products, He Simo said automation and intelligence processes are an important part of the group’s annual research and development (R&D) budget.

The enterprise had installed nearly 100 sets of equipment for automation in the past two years, He said, improving production efficiency and adding over 10 million yuan (US$1.36 million) a year in economic benefits. East Group plans to invest a large amount of its profits, equal to annual net profit, for more R&D.

“The group is leading over 600 suppliers in upstream and downstream industrial chains across the country to automate production and commercialise advanced products such as sodium-ion batteries and new energy storage systems,” He said.

According to a 2023 iResearch report, China’s robotics cover 65 industry categories and 206 subcategories. Automotive, electronics and semiconductors were still the mainstay industries for the technology’s application, with lithium batteries and photovoltaics emerging as stand-outs along with aerospace and home appliances.

Within the lithium and photovoltaic sectors, Soochow Securities said in June that annual replacement demand will rise from 150,000 units in 2023 to 250,000 in 2025 when accounting for the rapid pace of technology iteration.

The report predicted the density of robots in China’s manufacturing industries will also rise from 403 to 496 robots per 10,000 workers by 2025, corresponding to a yearly operational stock of 1.52 million, 1.69 million and 1.85 million.

China wants to double factory robot density by 2025

With a dwindling workforce, China urgently needs to improve total factor productivity and labour productivity, the Journal of the China University of Labour Relations wrote in 2021.

Separate from any other factors, the ageing population will lower China’s economic growth rate by an annual average of 1.07 percentage points from 2020 to 2025, the journal said.

Another article released by Finance and Trade Economics predicted that the operational stock of industrial robots in China will be around 2.98 million by 2050, around the same time China’s working-age population is expected to fall to 810 million.

It’s actually helpful and benefits Chinese workers in the long run

“The ‘robot dividend’ would make up more than half of the future labour shortage, without taking into account the efficiency gains of the robots themselves,” the article said.

In addition, automation can help China maintain its competitive advantage externally – and often requires the hiring of additional staff to keep operations running smoothly.

“It’s actually helpful and benefits Chinese workers in the long run,” said Hu Haifeng, a senior automation engineer in Shenzhen. “Each industrial chain is quite long and a large part of it actually requires hiring a large number of workers.”

“If productivity does not improve, labour-intensive factories would have to move to other countries with cheaper labour costs anyway,” said Xue, the textile exporter in Zhejiang. “Only increasing unit productivity can keep supply chains …[and] give Chinese exporting manufacturers more time to solve the problem of shifting supply chains caused by geopolitics.”

“In the next 20 years, I think the impact of ageing on manufacturing is actually not that big,” said Jiao Yang, who works in the financing department of a Shenzhen-based robotics company. “Today’s middle-aged Chinese people are still willing to work until they are in their 60s or 70s.

“The real impact these next few years is lack of demand. That is, demand for Chinese factories to produce, not that the Chinese do not have enough labour to build.”