China’s ‘involuted’ new-energy industry is awash with overcapacity that could stall new economic driver

- Domestic demand is far from able to absorb all of the new EV batteries and solar panels, so Chinese manufacturers have little choice but to sell overseas – if they can

- China’s top leaders acknowledged this week that ‘overcapacity in some industries’ is among the major economic challenges to tackle in 2024

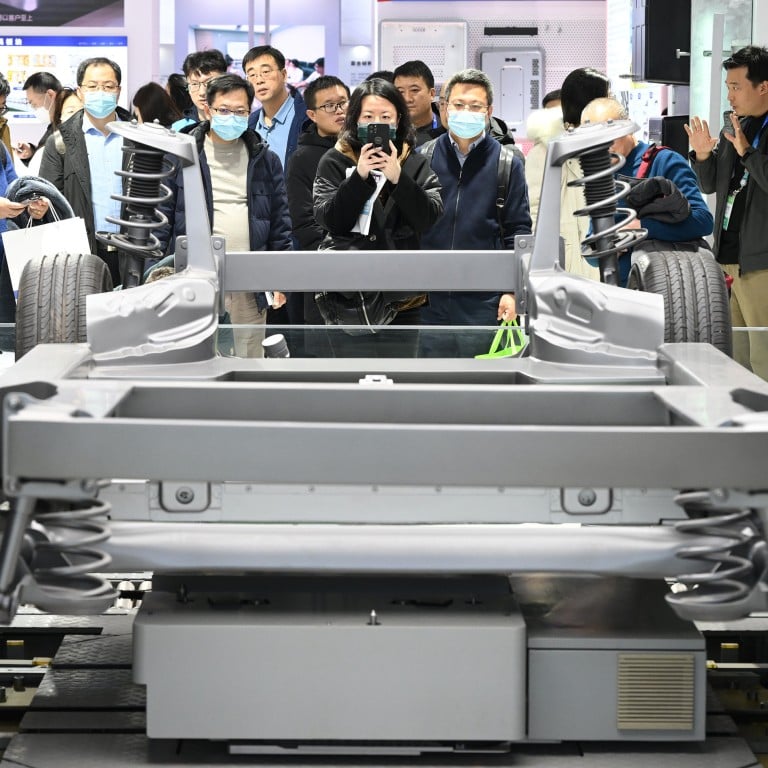

In the year since in-person trade fairs and expos resumed in China following its lifting of pandemic restrictions, exhibition halls across the country have been packed full of chatty sales managers from the new-energy supply chain.

From electric car batteries to solar panels, they peddle their wares to foreign businessmen and bigger industrial peers, handing out business cards and rattling off sales pitches.

In recent years, the term has become synonymous in China with being locked in an endless cycle of self-defeating competition. And perhaps nowhere is that better embodied than new energy.

From carbon cuts to common prosperity, China’s Politburo course corrects policy

And it is not just industry players who are affected. China’s overcapacity problem in the new-energy realm has far-reaching implications for the world’s second-largest economy. With traditional growth engines losing steam, the country is betting big on new energy.

Analysts say the best solution will be to export more new-energy goods, but they note that this would have to happen against the backdrop of rising trade barriers and some backlash in the West against low-priced Chinese products. Meanwhile, expanding new-energy infrastructure is also needed to boost domestic demand.

The [new-energy] sector has absorbed trillions of yuan worth of investment and employs millions of people

In the past decade, China has grown into the biggest player in the global new-energy industrial chain thanks to policy support, heavy government subsidies, and the world’s most complete manufacturing infrastructure network.

But in some provinces and cities where the industrial chain for electric vehicles has become a major economic engine in recent years, authorities have become increasingly worried about overcapacity, the industry insiders say.

“The [new-energy] sector has absorbed trillions of yuan worth of investment and employs millions of people, and it also plays an important supporting role in the national economy,” said Zou Ji, CEO and president of Energy Foundation China, a grantmaking group dedicated to China’s sustainable energy development.

But now, “there is insufficient downstream demand”, Zou said at an annual conference hosted by financial magazine Caijing last month.

China currently dominates 80 per cent of the global supply chains of photovoltaic products and automotive batteries, while more than 60 per cent of electric cars running around the world were made in China. As a result, there has been some backlash against China’s perceived monopoly in the sector.

China’s supercharged new-energy sector is propping up exports, but will it last?

The European Union has announced a subsidy investigation in China’s electric vehicle sector. It has also put forward the Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism, aiming to prevent “carbon leakage”, where carbon-intensive imports from countries with less-stringent climate policies outcompete domestic production.

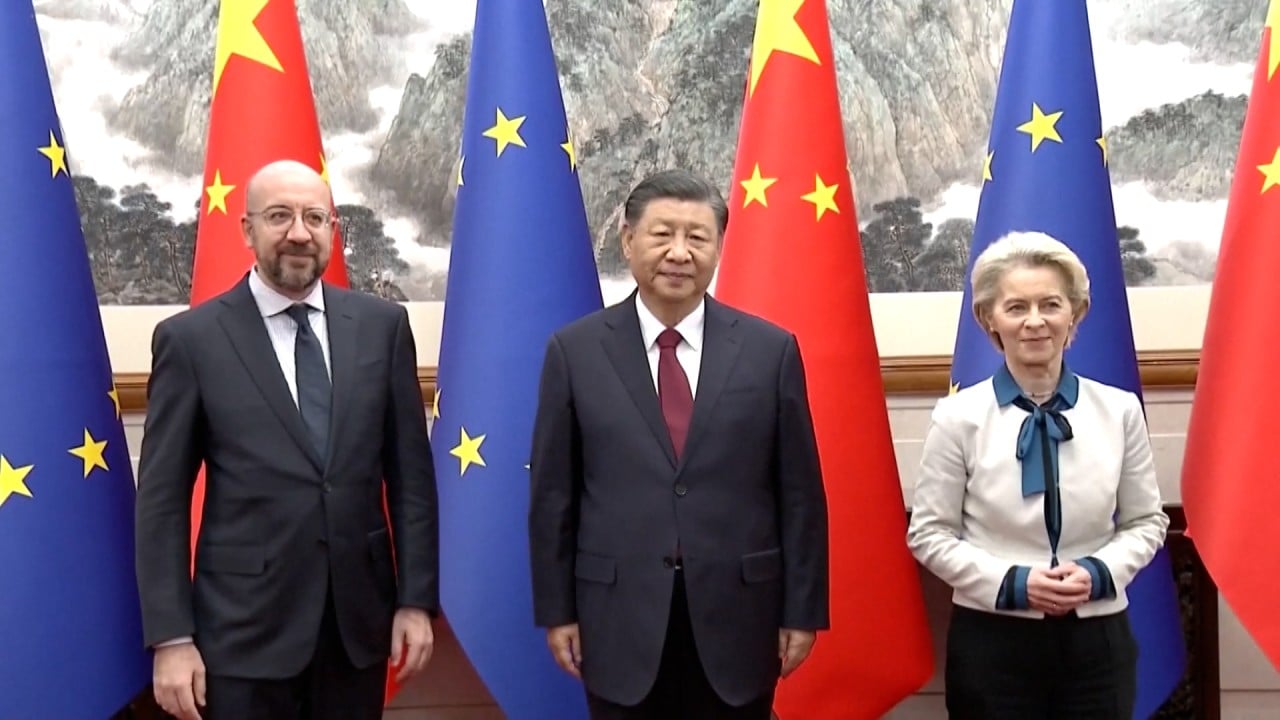

And when Chinese and EU leaders met during a summit in Beijing in early December, China’s overcapacity in the green sector was among the bloc’s major concerns.

India has imposed a series of tariffs on Chinese photovoltaic products, while Turkey has imposed a 40 per cent additional tariff on imports of vehicles with only electric motors from China.

“China has a big market, so production capacity can rise very quickly. But the bad thing is everyone can be jumping into the same pool at the same time and get ‘involuted’ quickly,” said Zhou Yuan, a managing director and senior partner of Boston Consulting Group.

Despite trade barriers, going overseas is still the best choice for the Chinese new energy sector, given the huge production capacity that the domestic market can never digest, she said during the same Caijing forum.

“Chinese enterprises must unswervingly go global, including to the Middle East and Europe, where there are still great opportunities. Of course, among so many countries, we must choose some markets with payment capabilities,” she said.

‘Phenomenal demand’ awaits Chinese firms in Saudi Arabia: investment minister

The Chinese government and enterprises should also strive for a bigger say in the formulation of international standards in the sector, she said.

In July, Cheng Yuan, a sales manager at a Tianjin-based lithium-ion battery manufacturer, went to Lanzhou, Gansu province, in a bid to find business opportunities in the Middle East.

At the Saudi Arabia counter of the Lanzhou Investment & Trade Fair, Cheng tried to learn from the exhibitors – from consulting firms to government officials of the country – about its capacity and demand for energy storage.

“We had overseas business in the United States, Europe and Japan, and we hope to expand the export market to Saudi Arabia,” Cheng said.

Zou of Energy Foundation China, meanwhile, reflected on how overcapacity stems from insufficient domestic demand and infrastructure.

For example, a large portion of the power generated by solar panels scattered across residents’ rooftops currently cannot be transmitted to a power grid, Zou added.

In the first three quarters of 2023, China’s newly added distributed photovoltaic capacity – such as from rooftop installations of solar panels – for the first time exceeded that of the centralised power-generation format where power is produced in a large plant, according to figures from the National Energy Administration.

In the long term, China should ramp up relevant infrastructure constructions to clear such hurdles, he said.

“Now the goal of the country has become to open up new markets for the industry and create new investment expectations,” Zou said.