Trade war, deglobalisation and technology: can container shipping weather the storm?

- The engine of globalisation has had a ‘torrid decade’, and the sector is facing another period of great volatility

- The US-China trade war is accelerating the regionalisation of supply chains, with the long haul sea freight business a natural casualty

When the first of Mandarin Shipping’s six small, modern container ships rolled into Hong Kong dock three years ago, Tim Huxley, the company’s founder, could not have anticipated the disruption to merchandise trade caused by the US-China trade war.

Mandarin Shipping’s Topaz class feeders, which are capable of carrying 1,700 20-foot equivalent units (TEU), are a drop in the ocean when compared with the world’s biggest container vessel, the MSC Gülsün, the 400 metre (1,312 foot), 224,986.4 tonne, 23,756 TEU goliath that sailed out of Tianjin Port on its maiden voyage last week. But arguably, they are more in tune with the industry’s future.

The company was established to service trade within Asia, a continent with almost 60 per cent of the world’s population and which, according to the Asian Development Bank, will double its share of the global economy to 52 per cent by 2050.

“We saw the demand for a focused, regional, feeder container operator catering to the customers here,” Huxley said. “More manufacturing moving across the Pacific to Mexico will obviously impact the trans-Pacific trade, but I think the movement of manufacturing within Asia is a particularly interesting one, that will be a real boost to intra-Asian trade.”

Hing Chao, executive director of another Hong Kong shipping company, Wah Kwong Maritime Transport Holdings, said that “the shift of manufacturing away from China to cheaper, regional markets in Southeast Asia has arguably led to more intraregional trade, which is backed up by the continued growth of intra-Asian container demand”.

“A few years ago, the major liner companies were predominantly focused on ordering larger and larger container vessels from shipyards, but recently this trend has stopped, and recent activity has been more focused on smaller feeder-container vessels,” he added.

This shift away from globalisation was laid bare by a study of 23 industry value chains across 43 countries released by McKinsey Global Partners in January. It found that in the mid-2000s, globalisation reached a turning point and that between 2007 and 2017, exports declined from 28.1 per cent to 22.5 per cent as a share of global gross domestic product (GDP).

Emerging economies over this time were building stronger domestic supply chains, reducing their reliance on imported goods, while their consumer markets became more important. Over the past decade, emerging markets’ share of global consumption rose by 50 per cent, McKinsey found.

Trade based on labour arbitrage – that is, companies taking advantage of cheap wages in developing countries – became less prevalent, declining to less than 20 per cent over the same period. Leaps in the development of digital platforms, automation, artificial intelligence and the internet of things, meanwhile, meant that the necessity for huge production facilities in low-cost manufacturing hubs has been reduced.

“In some scenarios, these technologies could further dampen goods trade while boosting trade in services over the next decade,” read the McKinsey report.

In industries such as automotive, computing and electronics, supply chains “are becoming more regionally concentrated, especially within Asia and Europe”, with companies increasingly looking to make their products close to market to be better able to cater for changing patterns in consumer demand and to reduce disruption from political risks such as the trade war, which is known as near-shoring.

In some scenarios, these technologies could further dampen goods trade while boosting trade in services over the next decade

And while these trends predate the US-China tariff war, this ever-escalating situation has sped things up. A survey by supply chain consultancy Qima, released last week, found that “near-shoring is becoming increasingly important” for buyers.

“The proportion of businesses that have already begun sourcing from new countries this year, or had plans to do so in the near future, was high on both sides of the Atlantic: 80 per cent for US respondents, and 67 per cent for those based in the [European Union],” the survey read.

None of this is good news for long haul container shipping, the workhorses of the sea. It was the invention of the shipping container by American businessman Malcolm McLean in 1956 that helped propel globalisation. By allowing goods to be packaged simply and uniformly, consumer goods became like any other commodity that could be easily shipped from one end of the world to the other.

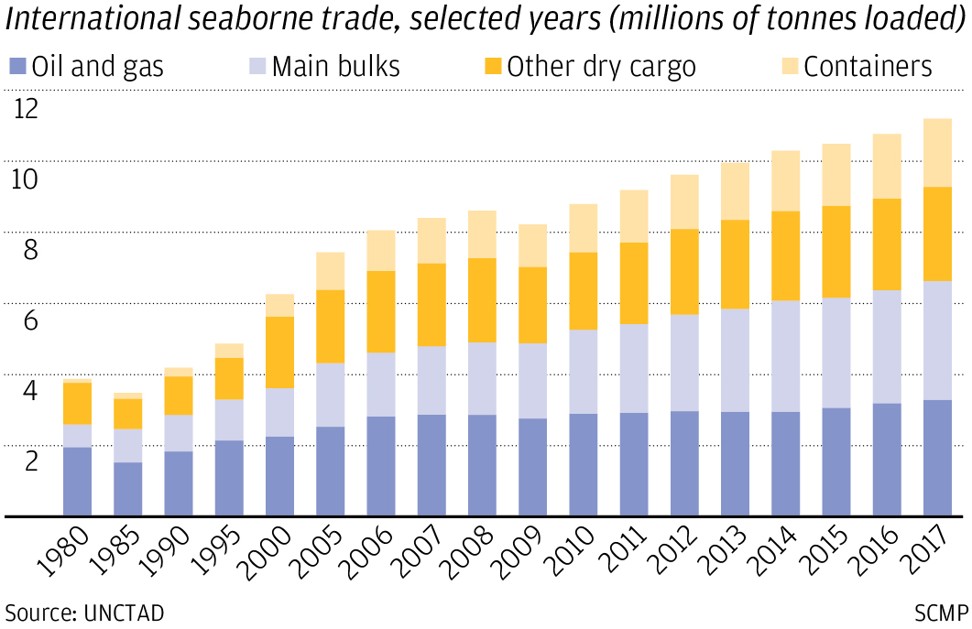

From 1980 to 2017, the volume of goods traded by container ships grew 1,834 per cent, while trade of other dry cargo grew by 125 per cent, according to the United Nations Conference on Trade and Development. However, in recent years, that growth has slowed significantly, while the industry has also been plagued by overcapacity issues.

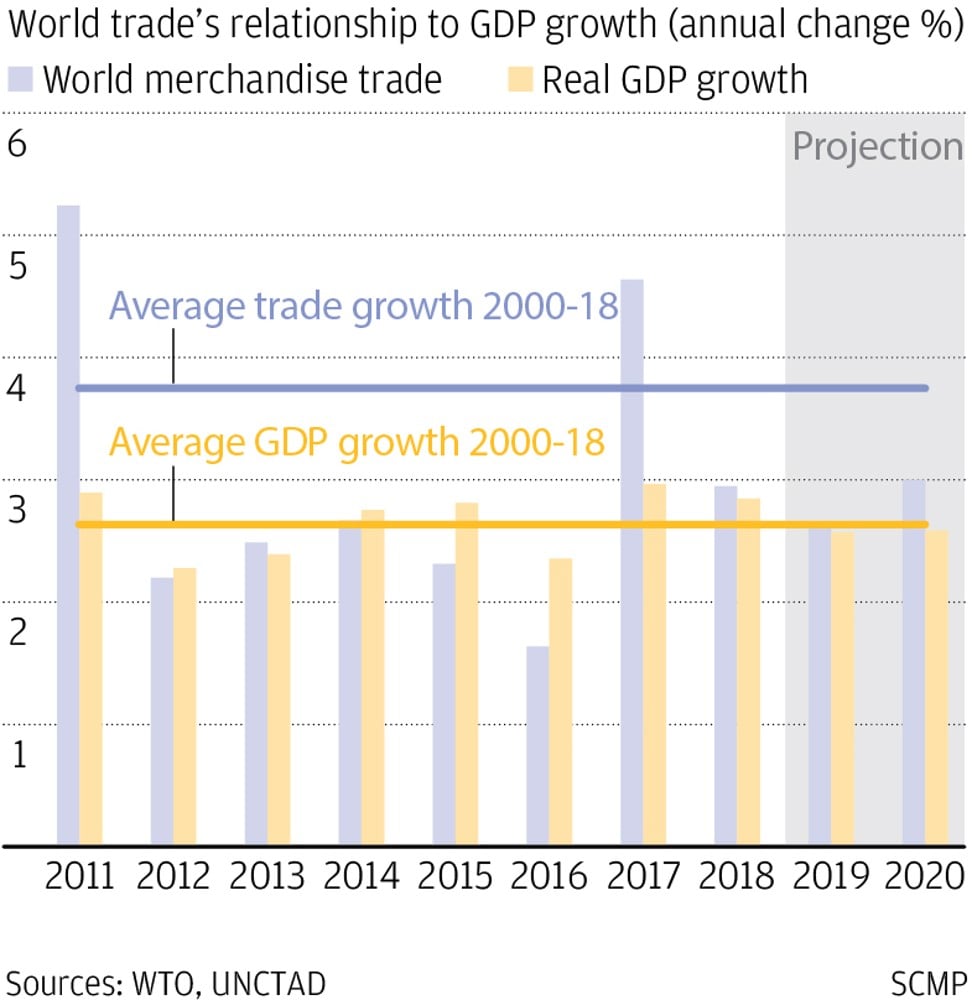

According to combined data from the International Monetary Fund and the World Economic Forum, the growth in global container transport will roughly track that of global economic growth over the coming years. As recently as 2017, it was growing at 6.7 per cent compared to 3.7 per cent for world GDP, and reported 14.2 per cent growth in 2010 as the world economy rebounded from the financial crisis and GDP grew at 5.4 per cent.

“There have been effects already and [regionalisation] will continue to affect container shipping. If you look at the last decade and the decade before that, container shipping trade always grew two to two-and-a-half times relative to GDP. So if you had 2 per cent of GDP growth, you would get 4.0 to 4.5 per cent of container trade growth,” said Martin Dixon, head of research products at shipping consultancy Drewry.

“Of course that drove the container trade, particularly in the last decade where you also saw container shipping trade growing with almost double-digit percentage growth year-on-year. But if you look at the situation now, that multiplier has effectively reduced down to almost one.”

Regionalisation could benefit those shipping firms operating shortened routes, Dixon said, but in some instances the shorter supply chain can be traversed better by land. With companies increasingly developing bespoke supply chains to service near-shore markets, such as China-for-China, India-for-India, Eastern Europe for the European Union, “a lot of these trends would be negative for shipping”.

One of the biggest beneficiaries of the trade war and the wider shift in supply chains is Mexico, with many companies leaving China to set up to supply the US market. This has been particularly pronounced in the automotive sector, with companies like South Korean pair Kia Motors and Hyundai Motor Company investing heavily in Mexican factories.

“We are becoming a more regionalised supply chain, as opposed to the globalisation model that we all embraced 20 years ago. But when it gets to short sea shipping, it is embraced more in Europe and Asia than it is [in the United States],” said Cathy Roberson, the founder of Atlanta-based market research firm Logistics Trends and Insights.

We are becoming a more regionalised supply chain, as opposed to the globalisation model that we all embraced 20 years ago

Roberson said that while certain routes, such as from the Mexican port city of Veracruz to Tampa on Florida’s Gulf coast, can be serviced by short-sea, most new Mexican exports to the United States will come by trucks and trains.

“There is talk here of utilising the Mississippi River more, because that was always the main transportation route when it came to short-sea shipping. But there are problems with that, with so much building along the river, issues with flooding and there's issues of the river drying out. We have a problem here of not investing in our infrastructure, we're missing out, I think, on a beautiful opportunity,” she said.

The Mississippi River begins in northern Minnesota and it flows generally south for 2,320 miles (3,730km) to the Mississippi River Delta in the Gulf of Mexico.

By no means will these supply chain shifts spell the end of the container shipping, however, it could mean a painful realignment.

“The great things about ships, the great advantage they have over a railway line, say, is that they can be moved,” said Guy Platten, secretary general at the International Chamber of Shipping. “Ships are adaptable. They can move where the markets are.”

Whereas many of the consumer goods used are transported via fixed route and scheduled sailings, other ships operate on a looser model known as “tramp trading”, “where they go from cargo, to cargo, to cargo, intimately adaptable and valued”, Platten said.

Furthermore, while container shipping has grown exponentially, it still accounted for only around 17 per cent of seaborne cargo volumes in 2017, with energy and raw materials making up most the goods shipped at sea.

“In the dry bulk and crude oil tanker markets, which are the sectors in which Wah Kwong operate, there has not been a noticeable shift towards shorter supply chains and, if anything, trade flows have shifted for various reasons – including politics – with the result that trade routes have got longer,” said Chao, referring to issues such as the Iranian-US stand-off which has forced oil tankers to steer clear of the Strait of Hormuz.

Drewry’s Dixon said container shipping has had a “torrid decade”, resulting in a spate of consolidation, as the industry tried to remove some capacity from the seas.

The continued escalation of the trade war will further fragment the global supply chain, meaning more volatility ahead for container shipping companies, and it remains to be seen how many of them can weather the storm this time around.