The Smithsonian is entirely to blame for its Bill Cosby problem

Even before the comedian was charged with sex crimes, the Institute made itself look foolish and conflicted by agreeing to show his art collection

“When we accepted the gift and loan, I was unaware of the allegations about Bill Cosby,” said Smithsonian National Museum of African Art director Johnnetta Cole last August in a statement published on the website The Root. “Had I known, I would not have moved forward with this particular exhibition.”

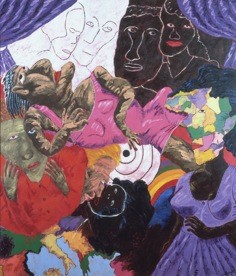

Cole, a close friend of the Cosby family, was discussing the museum’s exhibition “Conversations”, which pairs works from Cosby’s collection with African art from the museum’s holdings. The show opened in November 2014, and will remain open until January 24.

However, a month before the exhibition opened, a stand-up comic called Hannibal Buress revived long-simmering rumours about Cosby’s sexual behaviour in a video that went viral.

In September, after dozens of women had come forward to describe similar encounters with Cosby, Smithsonian secretary David Skorton defended keeping the exhibition open on free-speech grounds: “I believe taking down an exhibition will tarnish our reputation among museum professionals and others,” he said. “Creative activity of any kind can generate controversy. We will from time to time get beat up about some of these things.”

Cosby was arraigned in Philadelphia at the end of December and charged with aggravated indecent assault for an alleged offence from 2004.

Of course, the only serious controversy generated by the exhibition had nothing to do with its message; it was an ethical controversy about the conflict of interest that comes from showing a wealthy man’s art collection in a public museum, especially if the art has not been given or promised to the institution.