Review | How bohemian muso Nile Rodgers continues to inspire younger musicians

The uber producer and mentor to bands of various genres is living proof that disco is anything but dead

As the co-founder of the band Chic and a writer-producer for Diana Ross, Sister Sledge and Debbie Harry, Nile Rodgers created some of the finest recordings of the disco era. And he bristles at suggestions that the genre provided simple-minded music for narcissistic listeners and left no legacy after its 1975-80 dominance on the Billboard charts.

“It sounds simple,” Rodgers, 63, says, “until you try to play it. Let those rock guys try to play our records. They don’t even know those chords. They know A and E, but they don’t know the B-flat-13. The guys who played on those disco records were mostly jazz musicians who knew sophisticated harmonies. There was a lot going on around the dance beat on those records, and that’s why it has had such a lasting impact.”

Disco’s influence on Western pop music has been profound if seldom acknowledged. You can clearly hear the echoes of the late-’70s genre in three of today’s best-selling genres: dance-pop, EDM (electronic dance music) and hip hop. In each case, the chain of transmission went through Rodgers personally, so he is eager to set the record straight.

In 1979, for example, Chic enjoyed the summer’s biggest single with Good Times, an infectious disco anthem. By that fall, a single appeared that featured some young New Jersey vocalists, called the Sugarhill Gang, delivering rhyming verse in sing-song voices over instrumental sections lifted from Good Times. A DJ told Rodgers that it was something new – “rap music”.

The single, Rapper’s Delight, broke into the pop top 40, and hip hop emerged from the underground. Rodgers and his Chic co-founder, Bernard Edwards, were angry at first, but once they won a legal battle for a songwriting credit and the money started pouring in, they felt differently.

“We didn’t realise it was the start of a whole new cut-and-paste art form,” says Rodgers, who has bought the latest incarnation of Chic to Hong Kong twice in recent years to perform at Clockenflap.

“We soon realised that hip-hop was a lot like disco – an underground music that suddenly became viable in the marketplace and then a phenomenon that changed the world. But it all happened at the time of the ‘disco sucks’ movement, and the rappers soon learned that they shouldn’t say they liked disco. Instead they talked about James Brown and Miles Davis.

“But our records were perfect for hip hop. We would establish a groove with strings, keys, horns and the rhythm section; then we’d break it down. Listen to a record like Le Freak. On the chorus, when the singers say ‘freak out’, it’s just guitar and drums, which opens up the song. By reducing the density of sound, you create an opening, a bed for an MC to rap over, because there is more room for his words.”

Chic were sampled so often by rappers that Rodgers says the reports on his publishing royalties “resemble War and Peace, because they go on for hundreds of pages”. But even as Chic’s records were being sampled on the burgeoning hip hop scene, the backlash against disco turned Good Times into a last hurrah for the group. After that chart-topper, Chic never had a Top 40 pop single again.

The disco backlash reached its peak on July 12, 1979, when thousands of disco records were destroyed at Chicago’s Comiskey Park in the middle of a doubleheader between the White Sox and the Detroit Tigers. Rodgers says he and Edwards knew they were in trouble when they saw the hatred in the eyes of the fans storming the field. Nevertheless, three years later, David Bowie came calling, hiring Rodgers as a producer.

“We were surprised to learn that all these British rock guys loved Chic,” he recalls. “It turned out that the ‘disco sucks’ campaign was merely an American phenomenon. Duran Duran wanted to be Chic the same way we wanted to be Duke Ellington. Bowie and I both loved jazz. Everybody he mentioned, I knew, and everybody I mentioned, he knew. So I knew I could put the jazzy side of Chic on his music. The day I changed his song Let’s Dance to a jazzier vibe I said, ‘David, have I made this record too funky?’ ‘Nile, darling,’ he said, ‘is there such a thing as too funky?’”

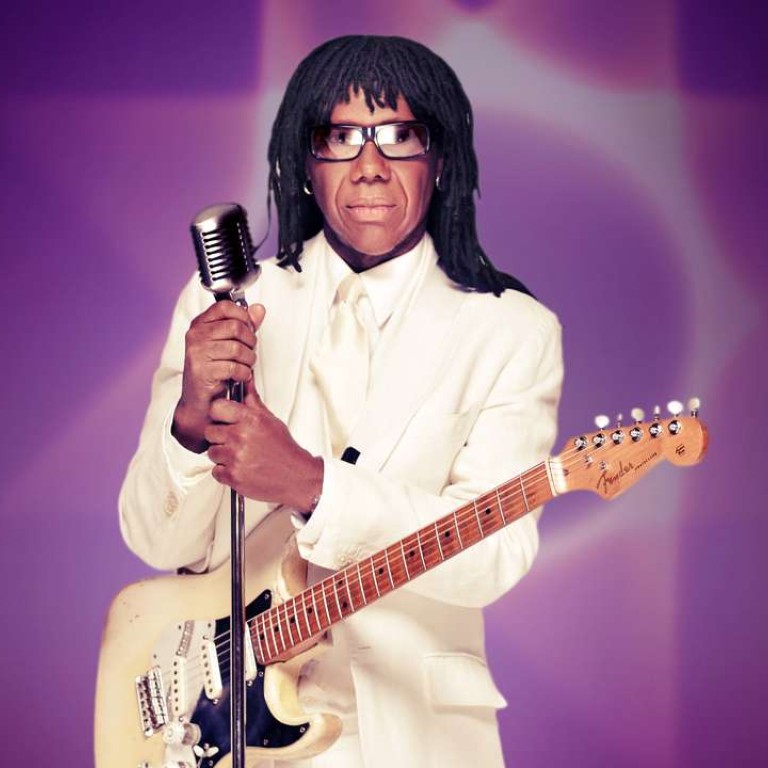

So it made sense that Lady Gaga hired Rodgers as the music director for her tribute to Bowie at the Grammy Awards in February. “LG”, as Rodgers calls her, sang snippets of eight Bowie songs in six minutes, and the connecting thread was Rodgers’s signature guitar fills, as rhythmically tight and as harmonically inventive as ever. During Let’s Dance, Gaga sidled up to Rodgers in his puffy white cap, grey suit and waist-length braids to put him in the spotlight.

Two years earlier at the Grammys, Rodgers played guitar as Daft Punk performed Get Lucky with Pharrell Williams and Stevie Wonder. Rodgers and Williams had written the international hit single with the French duo, who always appear in public wearing black space helmets, but Rodgers’ association with Daft Punk and the EDM movement went back much earlier than that. Daft Punk’s hit single Around the World, off their 1997 debut album, Homework, was built atop yet another sample from Chic’s Good Times.

In addition to writing, producing and arranging tracks for Duran Duran, Daft Punk and Sam Smith, Rodgers is working on a new Chic album. The first single, I’ll Be There, was released last year and topped the Billboard dance charts. The full-length album, Rodgers promises, will include such guests as Miguel, Janelle Monae and Lady Gaga. But it will also include repurposed tracks featuring Edwards, who died in 1996.

The irony is that Rodgers and Edwards didn’t start out to become a disco band. They tried for years to get a record deal as a jazz-fusion band and then as a rock band. It was only when they formed Chic, where the entire band dressed like models and played irresistible dance music, that they clicked. It was 1977, during the oil-embargo-fuelled recession, and Rodgers and Edwards consciously imitated the Roaring Twenties, when the party kept going even as the economy was falling apart.

Rodgers is no longer poor, but he’s still bohemian, ready to work with any young band trying to escape a bleak economy by creating an alternate reality of all-night partying. Even if those musicians never take their space helmets off.

The Washington Post