Sydney’s last stand: the residents holding out against gentrification

As private developers wait to pounce on expensive land occupied by public housing, the fate of an iconic building in inner Sydney has fuelled debate over the welfare of the city’s poor

It is one of the last few weeks in the slow emptying of Sydney’s Sirius building , and Myra Demetriou is keen to talk about spoons. Sitting in her waterfront apartment, the 90-year-old former church deaconess has relocation on her mind, and in a cabinet above her sofa, enamelled souvenir spoons keep track of every city she’s ever visited.

Demetriou lives alone by the harbour in the suburb of Millers Point. Her building, an architecturally adored icon of Sydney public housing, has found itself on land too valuable for its own good. In 2014, the New South Wales government told its 400 residents their government housing would be sold to private developers.

“Someone told me that in other states, in social housing, once you’re over 65 they can’t move you out,” she says. “Not here.”

In the nearby suburbs of Waterloo and Redfern, 4,000 social housing residents are facing a similar prospect. The Central to Eveleigh project is a A$550 million (HK$3.26 billion) revitalisation plan to turn rail yards into high-rises and public housing into part-private development. Its centrepiece is a new train station on land where the Waterloo estate now stands.

The median house price in Sydney has doubled since 2009, from A$550,000 to A$1.1 million. A report in January ranked the city the second least affordable housing market in the world – after Hong Kong.

This has sparked a government strategy affecting Millers Point and Waterloo: trade valuable inner-city social housing – never quite as dense as it could be, occasionally in disrepair – for newer, cheaper, more numerous housing elsewhere, easing the state’s 60,000 person-strong waiting list.

According to the state government, the sale of Millers Point alone will raise A$500 million and fund 1,500 new social housing dwellings in the city’s outer western suburbs. But to many, surging rents and the public eradication of the city’s few high-profile housing estates give the impression that inner Sydney is no longer a place where poorer people can live.

Philip Thalis, a city councillor and former public architect says there is a big stock of social housing in the city, but it’s declining. “The city of Sydney has a target of 7.5 per cent affordable housing, and that target is currently being exceeded. But as there is intense redevelopment with virtually no new public housing being built, that percentage is dropping just through the arithmetics of it,” he says.

In government parlance, “social housing” is an umbrella term that covers both public housing (fully government-owned) and “affordable” or community housing, run by third-party NGOs, charities or corporations, sometimes with government subsidies.

“In England it’s quite common to have an affordable housing target of 30 per cent, but here at the new Green Square development it’s only 3 per cent, which is a tragically low figure,” says Thalis.

Central to Eveleigh features only 88 affordable dwellings, built by a community housing provider in 2015. There are no plans for any more.

New South Wales has the largest social housing system in Australia, with 150,000 dwellings and 290,000 individuals. One in three tenants are children or young adults, and the state’s indigenous population is notably over-represented.

For Shaun Carter, critically feted Sirius is the blueprint for how to mix public and private housing in the inner city. “Sirius does all the urban design things right. It’s purpose-built housing for people that need housing. It puts people from the community back into the community.”

It’s a kind of modular living, reminiscent of Japanese capsules or stacked concrete boxes. Natural light, large windows and sea reflection give off a sort of aquarium feel, as if fishbowls were made pleasant for humans.

Demetriou has lived in Millers Point since 1972, and in the Sirius building since 2008. “At the time [in the 1970s], this was working wharves,” she says. “It’s always been a very close community. I immediately became friends with my neighbours, and you were never short of someone to talk to or ring up.

“But now, because so many people have moved away, they’re frightened they’re going to close the school down. There’s hardly any kids in the area. It’s very sad.”

The Waterloo estate, meanwhile, is home to 4,000 residents and six spindly towers. Unlike Millers Point and its genteel social mix, Waterloo has a rougher reputation; residents are open about past issues with drugs and crime. From mid-2018, Waterloo estate will be replaced by a new development: three times as dense and 70 per cent privately owned. The low-income housing that remains will be further sliced into public housing and non-government affordable housing.

If they dilute poverty it doesn’t make it go away, it just hides it

Sydney-wide, the median rent for a three-bedroom dwelling is currently A$1,000 a week, up from A$780 in 2010, while exit rates from social housing dropped from 8.8 per cent to 6.9 per cent between 2007 and 2013.

Aelwyn Richards, 64, has lived on the Waterloo estate for 25 years. “With gentrification, it’s usually an almost natural process. But what they want to do here is almost instantly move all these richer people in and reduce the number of povvos [poor people],” she says.

The government is adamant the increased density of this new development will allow the estate’s residents to return once work is complete. “There will be no loss of social housing, including in the Central to Eveleigh corridor,” a spokesperson says.

But residents fear a change in the community. Karen Brown, 54, worked as a cleaner for 15 years and has lived on the Waterloo estate since 1991. “Right now there are services being provided to lower socioeconomic groups,” she says. “If all these people move in here, it’ll change the whole socioeconomic mix and the average income, so then, do

those services go because we no longer qualify?

“Do they no longer want a drug counselling service running out of your courthouse? Or do you want a gym in there? If they dilute poverty it doesn’t make it go away, it just hides it.”

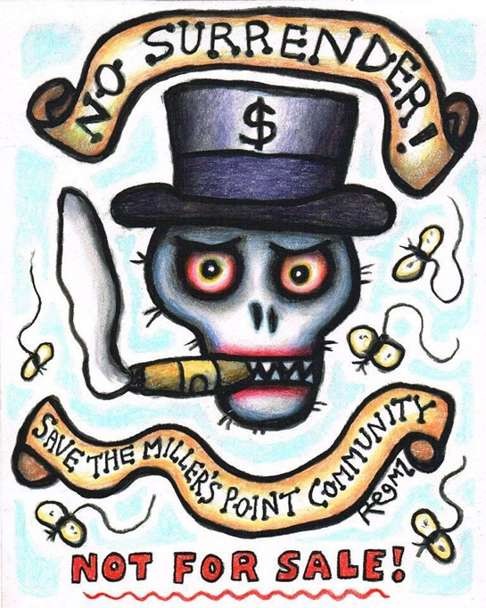

Jenny Munro has lived in Redfern since 1972 and her daughter lives on the Waterloo estate. She has fought gentrification in the area with a grim, physical determination – in 2014, she and other indigenous protesters formed a tent embassy on land slated for redevelopment, demanding a guarantee of low-income housing.

“Redfern was always a beacon for a lot of our people,” she says. “In the ’70s this was recognised Australia-wide as the heartbeat of the black political movement. This was a vibrant community, with in excess of 40,000 Aboriginal people living here.”

A 2011 census put the indigenous inhabitants at only 300 – in the very suburb where the first Aboriginal legal service and Aboriginal medical service were founded.

By the government’s own admission, Sydney’s social housing system is failing. A 2014 report described is as “ neither sustainable nor fair ”. The NSW government’s solution is a plan known as Future Directions. Over the next 10 years, it intends to hand over a third of public housing to independent community housing providers like those planned for Waterloo.

Janelle Goulding of City West Housing backs the plan, though residents fear it is a slow kind of privatisation. “This government has made it very clear they do not want to be involved in housing. Something drastic needs to happen,” she says. “Community housing has been around for 30 years, and if that’s what privatisation is, then that’s fine.”

But tenants like Paul want to live in publicly owned housing: “This is not just for us, this is for the next three or four generations. It’s a safety net for anybody who could need public housing in the future.

“But we have to be a little bit careful,” he adds, “because if we come across as arrogant or not grateful, it’s like what Dickens said: we’ve not only got to be poor, we’ve got to appear and be deserving.”