How Chinese gold miners helped build New Zealand and how discrimination drove them away

Late-19th-century Chinese migrants working New Zealand’s gold fields contributed considerably to the development of the island nation, but they earned resentment as well as riches, and little evidence of their presence remains

The peace among the lotus-filled ponds of Zili village is shattered by a cacophony of quacking ducks. The verdant countryside near Kaiping city, in China’s southern Guangdong province, is largely deserted. The younger generation have gone to the burgeoning towns and cities of the Pearl River Delta in search of their fortune. About 150 years ago, the exodus was overseas.

Nine diaolou buildings and six Western-style villas built by those who struck it rich are now protected by their status as Unesco World Heritage Sites. Diaolou are fortress-like towers that incorporated the latest Western-style building techniques at the time with traditional Chinese architectural cues, and stand testament to the enterprise of the adventurers who built them.

A sign in the local museum, which sits amid Zili’s lush rice fields, puts today’s population of Kaiping (Hoiping in Cantonese) at 680,000 inhabitants, although it adds curiously that a further 750,000 live overseas. Of those, 1,710 reside in New Zealand, it states.

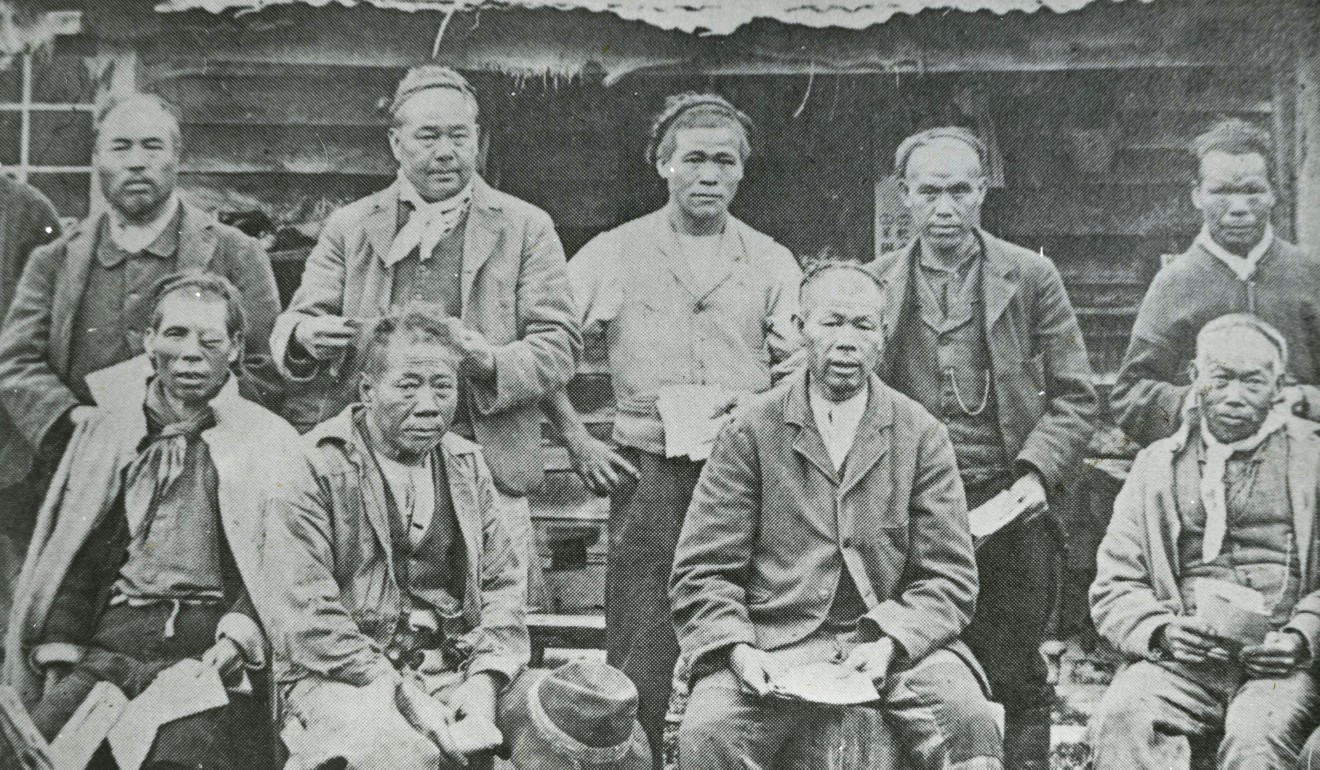

Kaiping’s association with the Land of the Long White Cloud dates back to the second half of the 19th century, when about 8,000 Chinese migrants worked the goldfields of the Otago-Southland and West Coast regions of the South Island. The great majority came from Guangdong province and in particular the area known as Siyi (Sze Yup): the four counties of Kaiping, Xinhui, Taishan and Enping.

Until the 1980s, most of New Zealand’s Chinese population could trace their ancestry back to these migrants, although some of the more successful ones were shopkeepers, or played some other such supporting role.

The economics of migration made sense. In 1871, a savvy Chinese gold miner was making about 77 old New Zealand pounds a year and saving two-thirds of his earnings, whereas a labourer back home made the equivalent of 12 to 14 pounds.

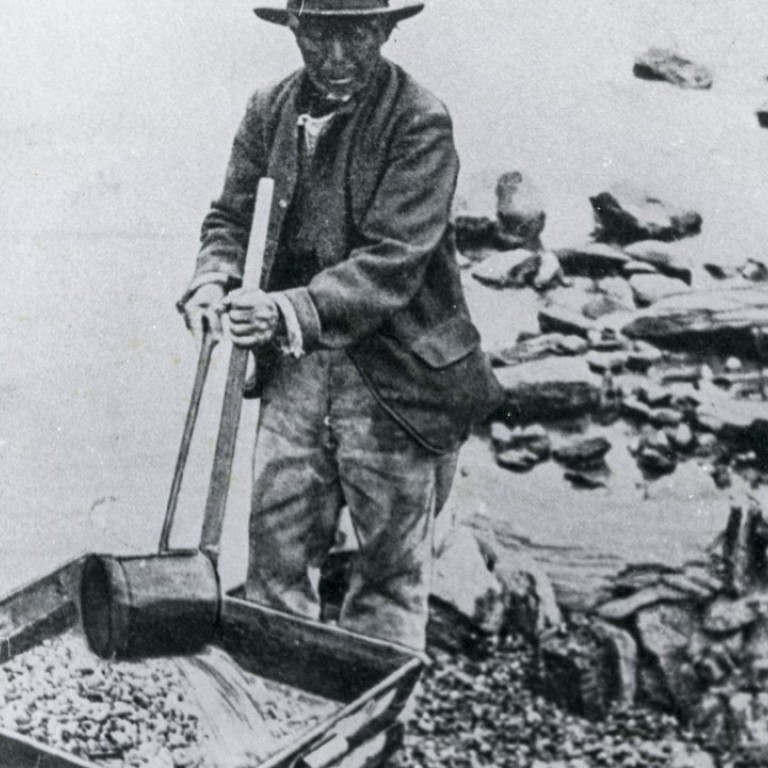

The early immigrants were initially treated with curiosity, but also a measure of respect. “It seems astonishing how these industrious people manage to get gold when everyone else has concluded there is none,” the Queenstown-based Lake Wakatipu Mail reported in 1870.

Julia Bradshaw, curator of human history at Canterbury Museum in Christchurch and author of Golden Prospects: Chinese on the West Coast of New Zealand, makes a similar observation. “They were such efficient miners that they recovered gold from areas that Europeans had given up on,” she says.

By around 1880, Chinese migrants in the Otago-Southland region, broadly covering the lower half of the South Island, made up an estimated 17 per cent of the population. They also accounted for up 40 per cent of all miners and produced 30 per cent of the gold.

How White Russian refugee crisis unfolded in China a century ago

At the same time in the West Coast region, they comprised about 5 per cent of the population. Earlier, in 1865, the first gold rush had almost ended in Otago-Southland and many miners began heading west. Fearing an economic collapse, the local Otago-Southland authorities recruited Chinese miners from Australia and directly from Guangdong.

A great number of them got their ticket to New Zealand via chain migration, with those already in the country helping relatives join them. There was a strong loyalty among those arriving from the same areas of China, and they usually worked in groups from the same clan or village.

Most lived a simple life, with the aim of saving between 100 and 200 New Zealand pounds. This would enable them to return home and buy a small farmstead – or even build a mansion like those in Kaiping. It was possible to achieve this within five years during the early years of the gold rush.

As the number of Chinese miners increased, and despite – or because of – their tenacity in finding gold where others had stopped looking, resentment grew among European settlers.

This soon started to spill into the media. Upholding tradition was an important link to the Chinese community’s roots, and the Lunar New Year was always celebrated with enthusiasm. In 1885, Otago’s Tuapeka Times reported the celebrations caustically: “For the past week Arrowtown has been the centre of attraction for about 200 Chinese who have made the night hideous with their exploding crackers.”

Increasingly discriminatory anti-Chinese legislation followed. It culminated in 1896 with a 100 pounds poll tax levied on new Chinese migrants arriving in New Zealand, which naturally led to a drop in the population.

At its peak in the 1880s, about 1,800 Chinese were reportedly resident in the West Coast region, but by the turn of the century the number had fallen to below 500.

Much of what is known about the Chinese miners was recorded by the Reverend Alexander Don, a Presbyterian missionary and Cantonese speaker from Australia, who for decades visited the miners in remote locations. In 1911, he translated a couplet, probably from the Lunar New Year, that read: “From the south we wish the streams of wealth appear. To our village we return quite certainly this year.”

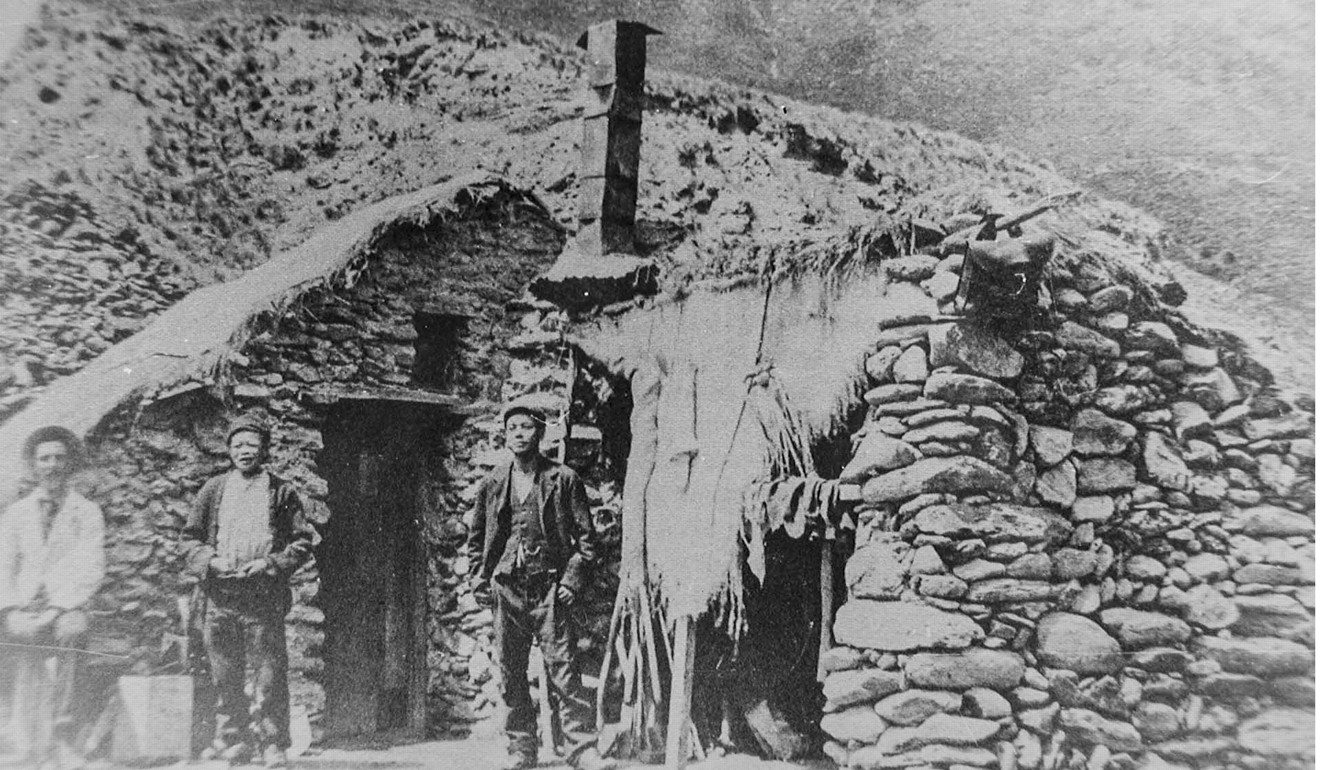

Few remnants of those early Chinese immigrants remain. The best preserved settlement is in Arrowtown, with 20 huts lining Bush Creek. Today, it comprises restored buildings, reconstructed huts and excavated foundations. At its peak, from the late 1860s to the 1880s, the camp had only 16 to 20 permanent residents, but a much larger floating population that fluctuated with the seasons; the frigid Otago winters made mining impossible.

What about the Chinese immigrants caught in Myanmar’s crossfire?

One of the most intact buildings is Ah Lum’s store, a modest structure of stone and wood topped with a corrugated iron roof. Back in the day, stores typically sold a combination of goods from back home along with local and European items. But they usually also played a more significant role. Most store keepers were literate and spoke English, so were able to offer translation and letter writing services in both English and Chinese. Miners, on the other hand, were usually poorly educated.

Ah Lum’s store was also an unofficial bank offering credit, and a meeting place and social centre. The loft above the store offered accommodation for those passing through the settlement.

It closed after the death of Ah Lum (also known as Lau Lei) in 1925, largely killing what little remained of the community. The last resident of the settlement, Ah Gum, died in 1932.

[The Chinese] developed significant market gardening operations … contributed generously to hospitals and spent freely when they were on a good claim, supporting the local economy

Today, Ah Lum’s is the only remaining 19th-century Chinese store from the southern goldfields. Excavations of the settlement in 1983 uncovered many artefacts, such as coins, cooking equipment, opium pipes and pieces from gambling games. These are on display in Arrowtown’s Lakes District Museum.

Over on the West Coast, the Shantytown Heritage Park has recreated the time of the gold rush with a collection of period buildings. Near a waterwheel is a reconstruction of Chinese huts with stories recalling the fate of some early immigrants.

Chinese immigrants have long been a part of Canada’s history

The vast majority of Chinese made enough money to return home. Some, through bad luck, opium addiction, gambling or by simply arriving too late, did not. Almost one in seven died in the goldfields. By the 1920s, most were too old to work. Since New Zealand excluded Chinese from the old age pension scheme, introduced in 1898, they were reliant on charity.

Little Kai’s story is among those at the park. He lived in a hut near where the entrance to Shantytown is situated. Little Kai was one of the unfortunate miners, having lost an eye in an accident.

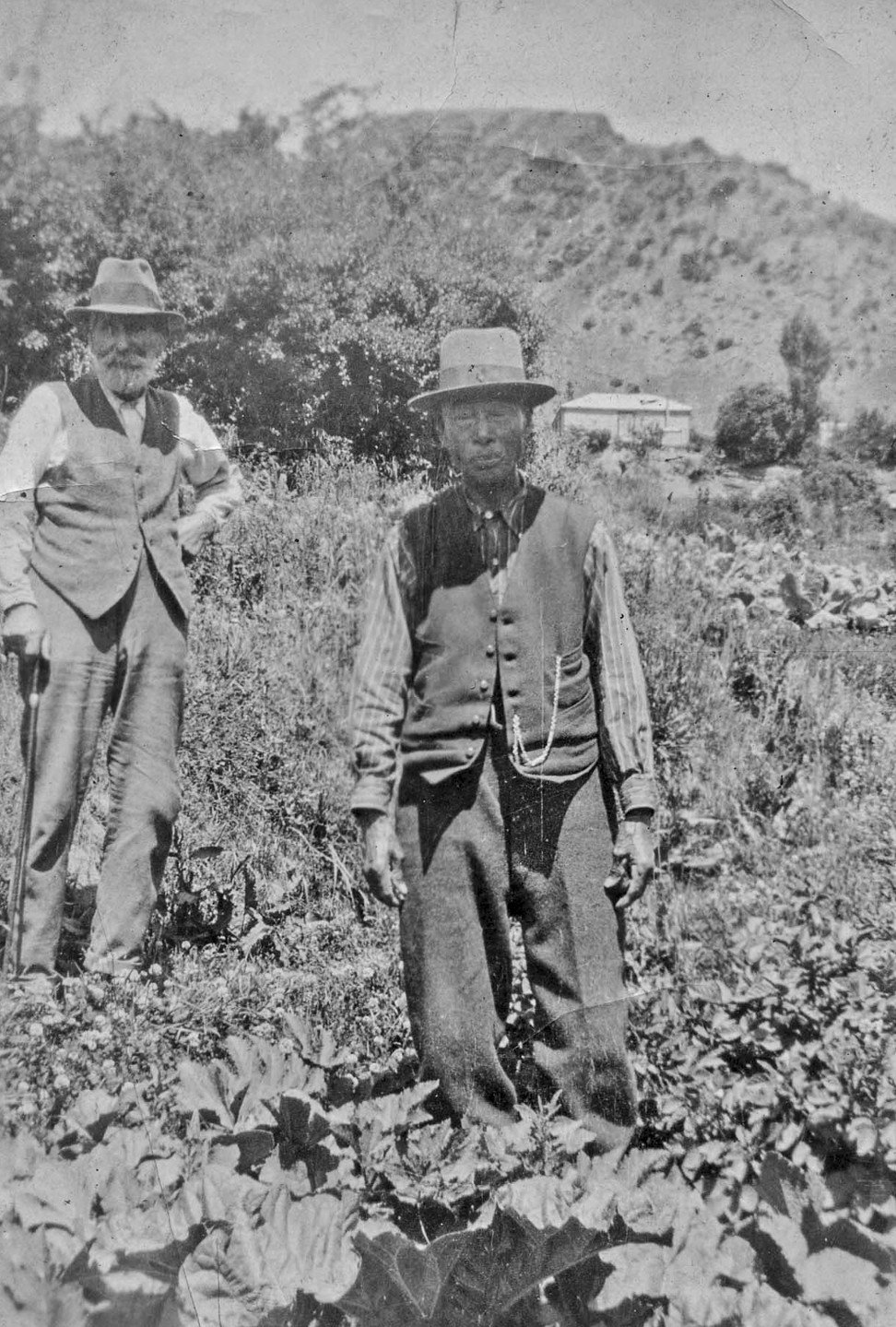

Some of the more successful miners married local women and chose to stay. Very few Chinese women had joined the migration, though successful merchants and shop owners could afford to bring brides over.

Ah Long, a storekeeper in the West Coast town of Ahaura, married Annie Tang when she was 17. In 1932 their son, Harry Long Kin-hong, went to Hong Kong and became engineer superintendent for the Hongkong & Yaumati Ferry Company – a post he held for 35 years.

One Kaiping native, Chew Chong, became one of the most successful Chinese immigrants to New Zealand. He arrived in Otago in 1876 and discovered Jew’s ear fungus (Auricularia cornea) in the bush. He paid others to collect it and exported it to China, where it was a delicacy. He later ventured into the dairy industry, earning a reputation for producing some of the best butter in the then British territory. He married a local woman and was survived by six children.

Although there are few tangible remains from the era of the gold rush, Chinese immigrants undoubtedly contributed considerably to the development of New Zealand. Along with miners from elsewhere, they paid gold duty to the central government, which was spent on public works throughout the country, Canterbury Museum’s Bradshaw says.

“In addition, they developed significant market gardening operations, which helped feed the local population,” Bradshaw adds. “The Chinese contributed generously to hospitals and spent freely when they were on a good claim, supporting the local economy.”

When Hong Kong’s dentists were nearly all Japanese, and why

In 2002, the New Zealand government issued a formal apology for the discrimination against the early Chinese settlers.