Shenzhen village plays host to Hakka descendants – including Jamaican/African Americans

After years of wondering about their roots, visitors from around the world descend on a Shenzhen village to celebrate the 200th anniversary of their ancestral home – and meet relatives for the first time

Firecrackers start the festivities to mark the 200th anniversary of the completion of Luo Shui He, a walled village in Shenzhen’s Longgang district, in southern China.

A lion dance then welcomes visitors from the United States, Canada, Britain, Malaysia, Singapore and other parts of China, all of whom can trace their bloodline to Luo Ruifeng, who lived 2,000 years ago.

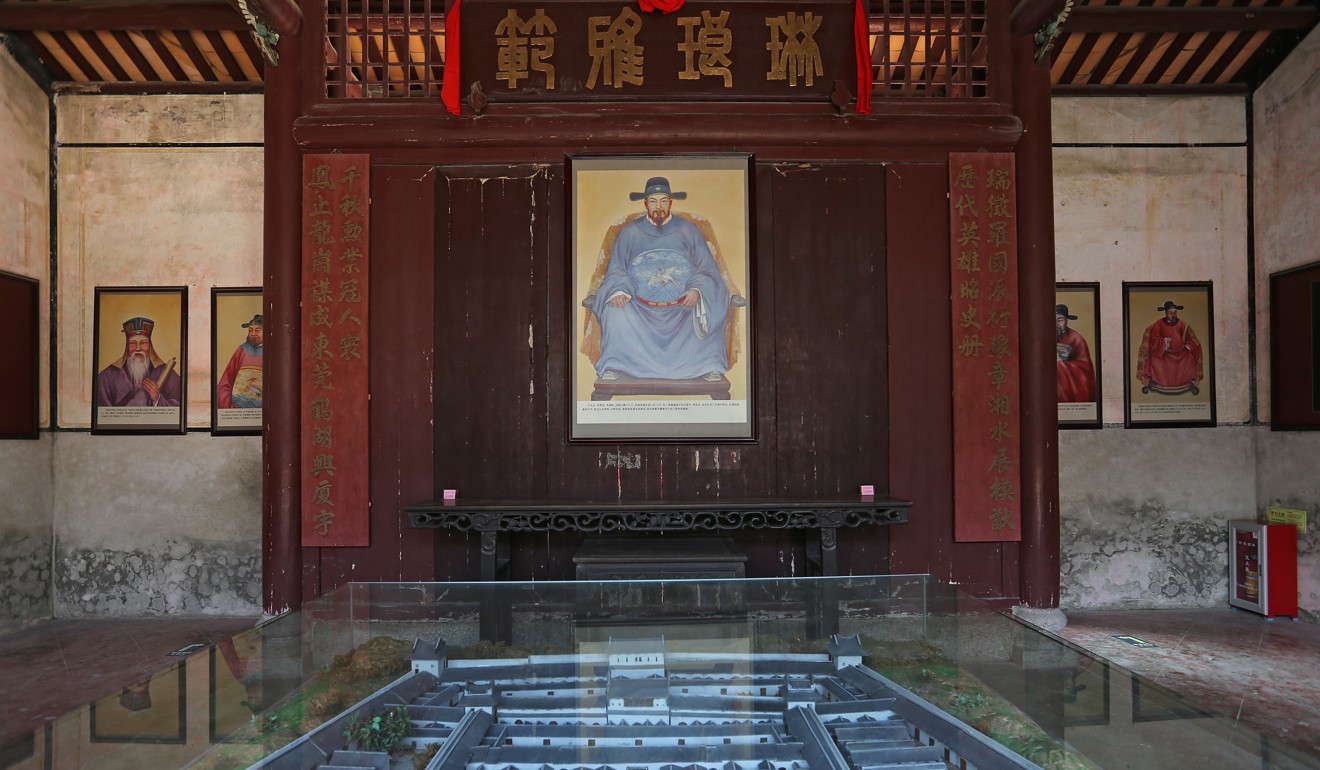

The celebrations, at what is today China’s largest Hakka museum, also called Crane Lake Hakka Village, were initiated by a woman who doesn’t even look Chinese.

“My mother looked Chinese and I looked black,” says Paula Williams Madison, who was raised in New York’s Harlem district. “My father was African-Jamaican, and so my mother was very out of place in our neighbourhood.”

From Harlem to China: how an African-American tracked down her Chinese grandfather

Madison’s grandfather, Samuel Lowe (or Luo Dingchao), was from Luo Shui He and left China to work in Jamaica from 1905 to 1933. There, he had three children with two local women.

Madison visits Luo Shui He regularly to connect with the grandfather she never knew, and to keep up with what’s happening in the village.

This time she was thrilled to see photos of herself and her brother Elrick Jnr on a wall along with their Chinese names and short biographies. Next to them is a picture of Luo Qifang, or Arthur George Lowe, who was an architect in Jamaica, and who died last year in the US. Daughter Liana Lowe proudly posed next to the photo for some smartphone snaps.

Chinese teenager reunited with family 16 years after being snatched from his home

The 24-year-old, Miami-based graduate in hospital administration says she was overwhelmed to be at Luo Shui He – her first time in China – and to learn more about her father’s Chinese roots.

“My dad asked me to go to China with him when I was about 12 years old, but I didn’t … I had pre-teen angst,” she says, with some regret. “I wish it had happened a long time ago, but I will keep coming.”

She found out about Madison and her documentary through a cousin who had seen it. Madison encouraged her to join the trip.

Lowe’s three older siblings had visited China with their father but didn’t join her this time, and she now wants to learn more about her Chinese heritage.

Patrick Lowe, 52, says his father was born in Jamaica but spent his early years in China before going back in his late teens or early 20s. He had always felt China was his real home. “Samuel Lowe, Paula’s grandfather, accompanied my father and my uncle Winston back to China when he was really young and needed an adult to accompany him,” he says.

Chinese girls return to orphanage 14 years after adoption by US families to highlight plight of ‘left-behinds’

Patrick Lowe contacted Madison about four years ago, after reading her book. “When I read the book, it was about more than the village. Paula talks about growing up, and in a strange way I could relate to that,” he says.

“I was an outsider too, growing up in Jamaica, where in my class 90 or 95 per cent of the kids were black. The only other non-black was my cousin. We just grew up in that environment because that’s all we knew.”

Patrick Lowe first visited Luo Shui He in 1992, and this is his son’s second trip to the ancestral village, which he hopes has sparked some interest. “He’s been taking pictures and seems proud that his ancestors can be traced back to 1006BC. It is something to be proud of,” he says.

The 23-year-old is proud of her identity. “I knew I was Chinese, but I didn’t necessarily know what it meant to be Chinese until I actually came here. Previously, I grew up in the US thinking of myself as a black woman, and now, learning more about myself as a part Chinese woman has helped me gain insight into what it’s like to be part of two worlds,” she says.

Jones is motivated to learn more Chinese – Cantonese and Mandarin – beyond the few words she has picked up to deepen her understanding. As the oldest of her generation, Jones is also keen to maintain the links between East and West.

Humanity’s strange new cousin is shockingly young – and shaking up our family tree

Watching people in the crowd meeting new relatives for the first time or catching up with others, Madison is pleased, but also feels an obligation.

“Because I’ve shot this documentary and written this book, almost all of them [relatives] know who I am, even if I don’t necessarily know who they are. I feel almost embarrassed because that’s not the personality that I have. But I have to have this personality because it’s important to me, not that it’s a Luo family gathering, but … that Hakka people continue what our ancestors started, which is families migrating, travelling the world and always coming back together.”

“What my mother experienced was, if you get too far away, you don’t know how to get back. My mother didn’t grow up as part of the Lowe family; my grandfather looked for her for the entire 15 years he was in Jamaica until he returned to China, but he couldn’t find her. I think it’s important that all our family members have the opportunity to come back every once in a while. Come back and know that you’re connected, you’re grounded, you’re not floating alone in the world. You’re not lost.”

She says China cannot ignore this growing multi-ethnic diaspora, which challenges the definition of being Chinese. “You cannot tell me that I am not Chinese and you cannot tell me that I’m not Hakka, because I am,” she says.

“So what do you do, China?” she asks. “You need to welcome us. Welcome us as we come home because we are also products of Chinese culture, civilisation, principles, and we have an allegiance to our Chinese ancestry, our heritage. That’s why I want people to come here, to Luo Shui He.”

‘Do you know this man?’ – tracking a father with old black and white photos

British-born Chinese Isabel Lo came to Shenzhen with an iPad of scanned black-and-white photos from her father’s albums. Before he died, four years ago, her father had hoped Lo, 41, would visit his ancestral village, Luo Shui He.

He didn’t give her much information on its whereabouts, however. In his limited English, he explained that it was a “castle” – possibly a reference to it being a walled village.

With her husband and two boys in tow, she was in Luo Shui He meeting people and showing them her pictures to see if they recognised anyone.

Lai Chi Wo Village - abandoned dwellings in a 400-year-old walled Hakka village in Hong Kong

“When my dad passed away, I didn’t know who to contact [because he was an only child],” Lo says. “I only recalled meeting Lo family members on two occasions, and one of them was in 2007, when my dad’s cousin Lo Ki-shing invited us to his daughter Sabina’s wedding in London. I only knew the bride’s name and managed to find her on social media. Since then she has been tagging me with anything to do with Chinese culture she thinks will interest me, and she tagged me on the Finding Samuel Lowe: from Harlem to China documentary.

“When I saw it I was really excited and I commented I would really love to visit there. I’ve always wanted to go there. It was my dad’s dying wish for me to go there. And then Paula [Madison] said, ‘you must be my cousin’.”

“It’s very exciting to find out the people in these pictures are my grandparents. Before, I had no idea what they looked like. When I was young, I heard rumours that my grandmother was blind, and now I’ve got confirmation, and that she might have gone blind after giving birth to my dad. I also got to see where my dad was probably born and grew up until he was 23,” says Lo, from Northampton, in the English Midlands.

At the anniversary festivities, Lo reunited with Lo Ki-shing, her father’s cousin, who had some distressing news.

“It’s also been upsetting for me because he told me my grandfather was a heavy drinker and smoker,” says. “There was so much sadness in him [my paternal grandfather].”

The place that Lo was shown had been destroyed by fire as the result of a Japanese attack, and subsequently rebuilt.

In an email, Lo wrote that she intends to keep in touch with the Lo/Luo/Lowe family members, and document as much as she knows for the next generation. “In particular, I would like my children to grow up being proud and knowledgeable of their Chinese heritage.”