Indonesian archaeologist recalls Flores ‘hobbit’ fossil find 15 years on, and what it meant for him and Indonesian archaeology

It was a discovery that amazed scientists – a fossilised relative of humans just 106cm tall. Emanuel Saptomo recalls what happened next: a chase around town buying nail polish remover to use as adhesive, and a decision to forgo air travel for a ferry and bus ride, with an extra ticket for ‘Flo’

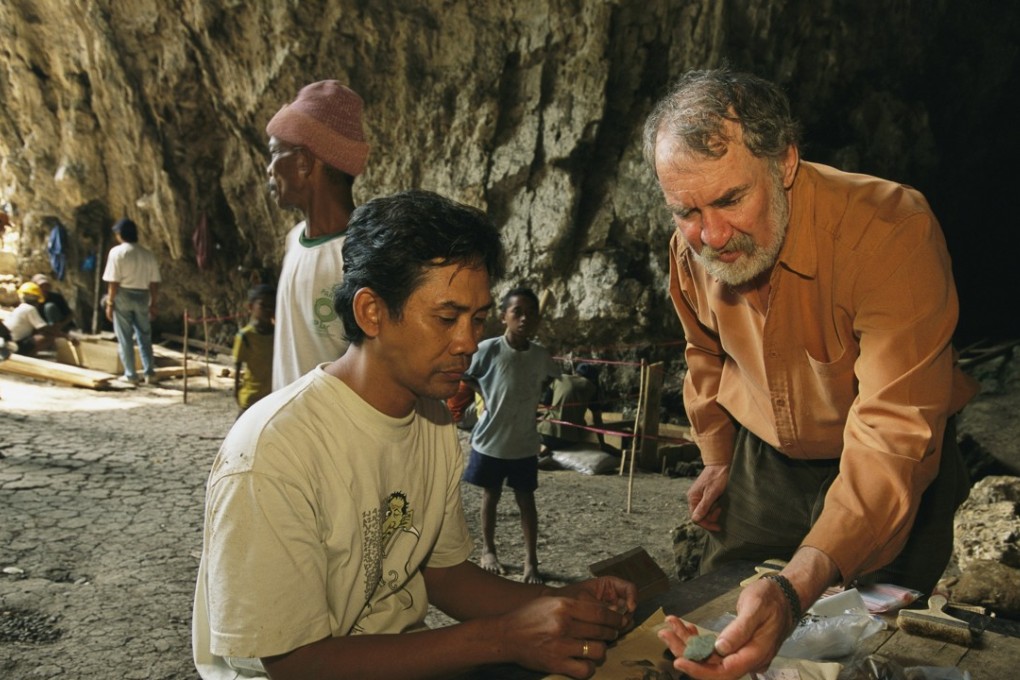

Indonesian archaeologist Emanuel “Wahyu” Saptomo’s eyes dance as he recalls the discovery of fossil “Flo the hobbit” 15 years ago. It was the evening of September 6, 2003, during a dig in the cathedral-like limestone cave of Liang Bua, on the sparsely populated island of Flores.

A team from the Indonesian National Research Centre for Archaeology (Arkenas) was looking for evidence of Homo sapiens migration from Asia to Australia when they uncovered the remains of a small hominid, whose origins continue to mystify scientists to this day.

It was Wahyu’s first professional dig. More than a decade later he was one of four Indonesians featured on “The World’s Most Scientific Minds 2014” list based on research citation analysis compiled by Thomson Reuters. He was credited alongside colleagues and fellow archaeologists Thomas Sutikna and Jatmiko, and late palaeontologist Rokus Awe Due.

Indonesia’s ‘hobbits’ disappeared about same time modern humans arrived in Southeast Asia: report

As members of Arkenas prepared to return to Flores to continue fieldwork at the site this month, Wahyu recalled how, on that eventful Saturday evening, assistant archaeologist Benjamin Tarus was excavating the ground with a trowel 10.7 metres (35 feet) below the cave floor. As night fell, Tarus’ trowel uncovered an object that on further exploration was revealed to be a fossilised, human-like skull.

Returning at dawn the next day, the archaeologists carefully continued their excavation, eventually unearthing an almost intact hominid fossil only 106cm (3 feet 6 inches) in height. It’s brain, it was later determined, would have been the size of a grapefruit.

Wahyu says his heart was racing at the unprecedented discovery. The remains were later classified as Homo floresiensis and were found to be about 68,000 years old.