Islamist militant prisoners freed in Indonesia turn a new leaf via schemes to change their radical beliefs and return them to society

Non-profit and state groups work to deradicalise jailed Islamists militants and empower them to make an honest living, but critics say such schemes fail to reach hardliners and many who take part had already abandoned radicalism

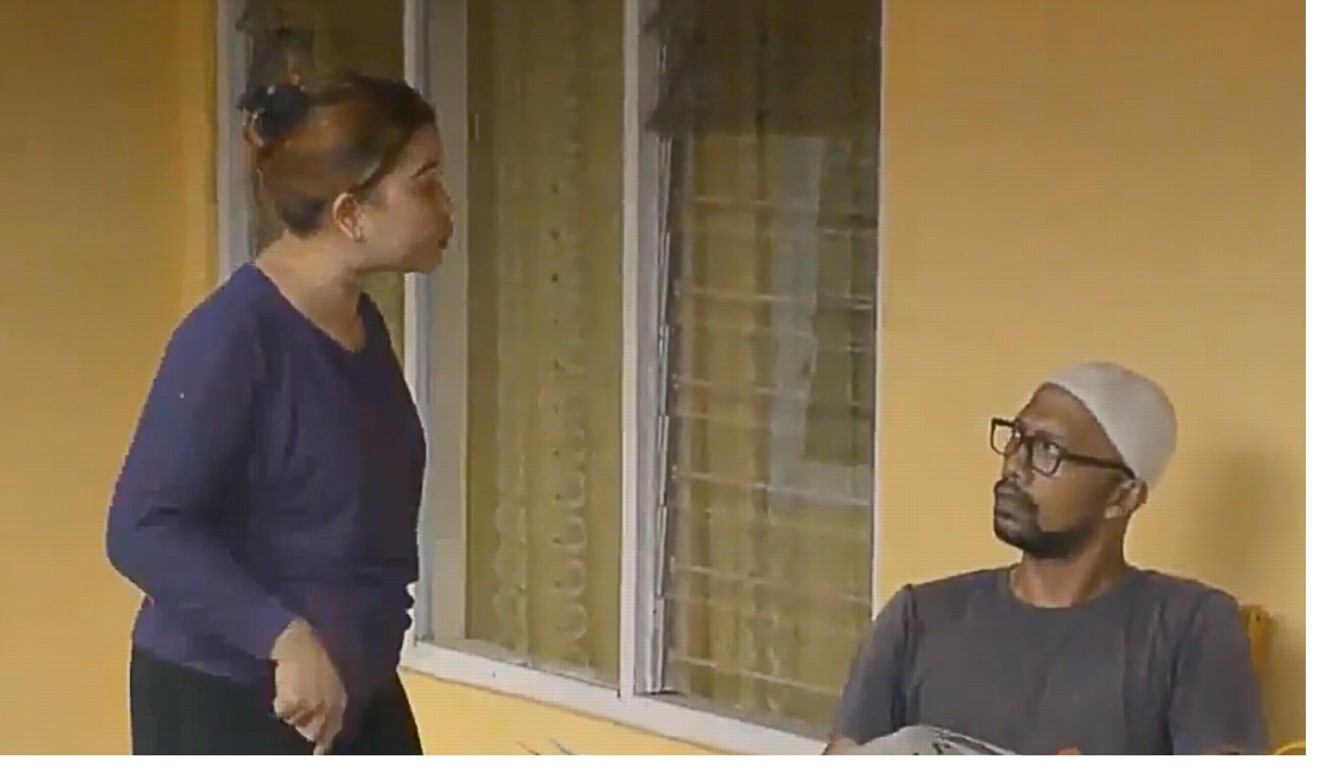

Arifuddin Lako never had formal training in filmmaking, but in February he released a 40-minute film in the Indonesian capital, Jakarta.

Titled Jalan Pulang (The Way Home), it tells the story of an Islamist militant combatant and former prisoner’s attempts to repent for his past mistakes. The story draws on Arifuddin’s personal experiences. Also known as Iin Brur, Arifuddin is a former militant.

Now 40, he grew up in Poso, in Indonesia’s Central Sulawesi province. In 1998, just after he graduated from high school, a violent conflict erupted in Poso between Muslim and Christian communities, resulting in about 1,000 deaths.

Indonesian domestic helpers on sex abuse, slavery-like conditions they endure working overseas

“At that time, there were riots and chaos in Poso,” Arifuddin recalls. “I had to leave the family home. I just wanted revenge.”

In 2000, Arifuddin started attending Koran reading sessions, and joined a group that offered military training in the jungle. Arifuddin believed Poso was at war, so it was justifiable to attack and kill the enemy in self-defence. He didn’t realise at the time he had become a member of JI.

Arifuddin found himself on a police wanted list in 2006, after he and associates executed a prosecutor involved in a trial related to the Poso conflict. As a result, he fled to Palu, the capital of Central Sulawesi. After almost three years in hiding, Arifuddin yearned to see his parents again, and began to regret his actions.

Indonesia slammed over leniency for ‘Bali bombings cleric’

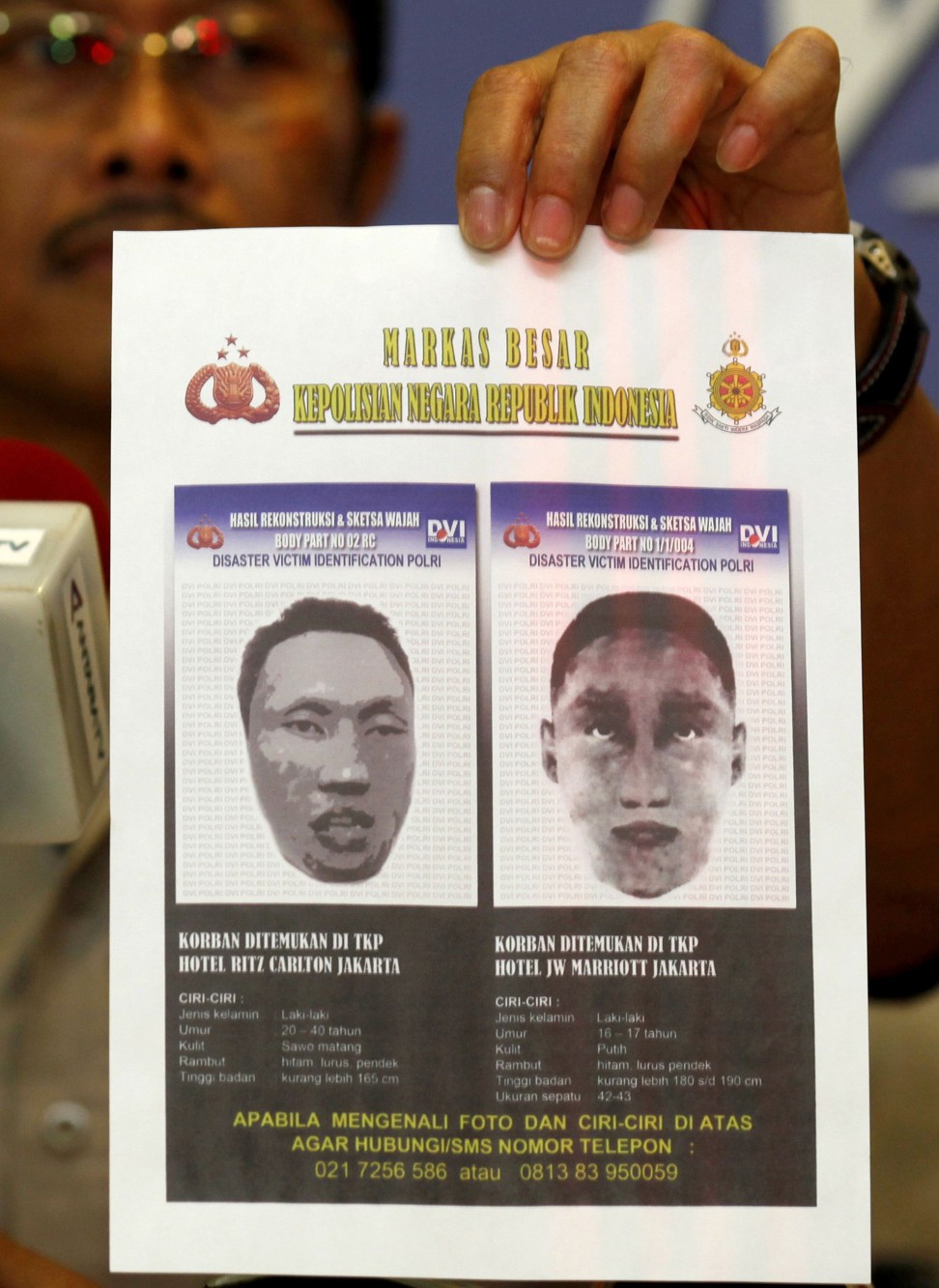

Meanwhile, JI was committing increasingly violent attacks on places frequented by foreigners, and in 2009 the group bombed a five-star hotel in downtown Jakarta. Arifuddin says that repeatedly seeing photos of the hotel bombing in the news scared him into believing he could be arrested at any time.

When he eventually returned to Poso to visit his parents, his mother encouraged him to turn himself in. In November 2009, accompanied by two religious leaders, he presented himself to the police in Palu and confessed. A year later he was sentenced to eight years in prison, but was released early, in 2015, for good behaviour.

Arifuddin has since set up the non-profit group Rumah Katu Community, with the aim of fostering peace and pluralism. He is also involved in a programme to “deradicalise” former Islamist militants released from prison in Poso.

The programme was established in 2012 by the Indonesian National Agency for Combating Terrorism (BNPT). Irfan Idris, who is its director for deradicalisation, says the programme takes a three-pronged approach: coaching, mentoring and empowerment.

“We have various programmes because we target those still in prison and ex-convicts who have been released,” Irfan says.

Being branded a terrorist and stigmatised is difficult – probably even more difficult in society than in prison

He says they first assess how best to approach an individual to change their radical beliefs. It is also important to offer opportunities for economic empowerment, he adds.

“For example, if art can get through to them, we’ll use art. We collaborate with psychologists, customary leaders and artists,” he says.

To date, 325 former militants have taken part in the deradicalisation programme, 128 of whom have joined the agency to join the fight against extremism.

The approach has its critics, though. Sidney Jones, director of the Institute for Policy Analysis of Conflict, says the BNPT’s programme is ineffective because it is not well targeted. According to Jones, many hardcore ideologues refuse to take part in the programme.

Solahudin, a researcher from the Centre for Terrorism and Social Conflict Study at the University of Indonesia, agrees. Solahudin, who goes by one name, says participants are usually those who have already disengaged from hardline groups and have vowed to refrain from violence.

In 2014, Aman founded Jamaah Ansharut Daulah, a militant group that supports IS. Despite being in jail for inciting acts of terrorism, he inspired other radicals to carry out attacks across Indonesia through recorded sermons and writings.

THE INDONESIAN VILLAGERS WHO LIVE WITH THEIR DEAD

Jones says scholars who have interviewed terrorists and ex-combatants find that the most common reasons they give for turning their backs on extremism is a sense of personal awareness, or for family reasons.

One famous case is that of Umar Patek, a JI member who became one of Indonesia’s most wanted men after his involvement in the 2002 Bali bombing and other terrorist activities. He was sentenced to 20 years in prison in 2012.

In a TV interview from prison last month, Umar claimed he had decided to change his radical beliefs because of support from his family and the kindness of prison officials, who treated him like a human being. He apologised to the victims of the Bali bombing and their families.

Jones believes the deradicalisation programme should address whole families, because other members may also have become radicalised.

That seems to have been the case in the most recent attacks, in Surabaya, East Java. The instigators are thought to have been a couple – Dita Supriyanto and Puji Kuswati – who took their four children along with them when they carried out suicide bombings at three churches on May 13. Thirteen people were killed and dozens injured.

Solahudin criticises the BNPT for lacking a clear process to measure the outcome of its programme, however well-intentioned.

“First, the level of radicalisation must be measured,” he says, because the current process does not determine the degree of radicalisation before and after intervention.

Out of hundreds, only three repeated their mistakes. If that’s considered a failure, we accept it.

Doubts aside, it is necessary to find ways to work with convicted militants once they have been released from jail because reintegration into society is a challenge for them, observers say.

“Being branded a terrorist and stigmatised is difficult – probably even more difficult in society than in prison,” Sofyan Tsauri says.

Sofyan is a former member of the Mobile Brigade Corps of Indonesia’s police force, and was dishonourably discharged after being convicted of supplying arms to an al-Qaeda-affiliated extremist group in Aceh province. He says he decided to join because of the injustices he saw being committed against the world’s Muslims, and because he resented US hegemony.

Sofyan was arrested in 2010 and spent five years in jail. He claims it was during his incarceration that he decided to steer away from extremism because he realised many of the acts he had committed were against Islamic teachings. After his release, he worked with the BNPT, and the agency invited him to speak out publicly against terrorism.

Sofyan says he benefited from BNPT’s empowerment programme, which helped him find an income when he couldn’t get a job. However, the government’s deradicalisation programme does have flaws, he says.

He sees infrastructure as one of the biggest problems. The government has to build a better prison system, he says, rather than focusing on incarcerating militants, otherwise prison will simply be a meeting place for radicals.

Sofyan says he’s seen the effect prison can have on inmates who were merely sympathisers of terrorist groups. “They were put in jail and became radical; became worse,” he says.

Top Muslim fashion designer who shot to global fame is jailed for fraud

The deradicalisation programme is only open to those who have already been convicted and jailed. In a period that can last up to eight months after arrest and before trial, there is no official counselling available.

According to Jones, until 2011 suspected militants detained at the Jakarta police headquarters were given counselling by Ali Imran, a reformed militant and one of the masterminds of the Bali bombing – which had caused some concerns.

Suhardi Alius, head of the BNPT, says regulation mandates that the deradicalisation programme is available only for convicted terrorists. “As long as they’re still a suspect, we cannot access them,” Suhardi recently told weekly news and politics magazine Tempo.

Saving Yangon’s colonial buildings is about heritage, but also profit

On May 25, the Indonesian parliament passed new anti-terrorism laws in the wake of recent bombings. These laws, Suhardi says, give the BNPT a wider mandate to conduct the deradicalisation programme.

It is up to society to judge the success of the programme, he says. To date, Suhardi says, only three individuals involved with the programme have been involved in further acts of terrorism. “Let the people evaluate. Out of hundreds, only three repeated their mistakes,” he says. “If that’s considered a failure, we accept it.”