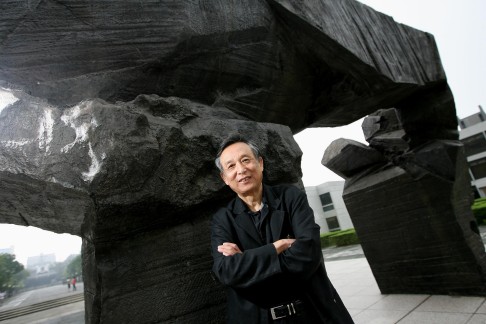

Meet Göran Malmqvist, Nobel Prize member and champion of Chinese literature

Göran Malmqvist is a member of one of the most influential literary bodies in the world, and a champion of Chinese literature, writes Janice Leung

When Gao Xingjian won the Nobel Prize for literature in 2000, Göran Malmqvist came under fire for not recusing himself in the awards process. Critics accused Malmqvist, a senior member of the selection panel, of a conflict of interest because he was a friend of the dissident Chinese writer and had translated many of his works.

A similar controversy emerged 12 years later when Mo Yan became the second Chinese author to win the prize.

Questions about his role in the choice of Gao and Mo for the Nobel Prize are perhaps inevitable. Malmqvist is the only sinologist among the 18 members of the Swedish Academy who decide on the award, and is widely assumed to be the driving force in their selection. Many believe his influence is all the greater since he translated their works for the academy to review.

At the same time, the authority of the Swedish Academy as an adjudicator of world literature is sometimes called into question.

The academy comprises mainly writers - novelists, poets, playwrights and screenwriters - along with some historians, scholars, literary critics and translators. All are Swedes and their primary role is to maintain the vigour of the Swedish language. Members meet weekly to select recipients for dozens of literary awards; the Nobel Prize for literature is just one of many that the panel bestows.

The prize was first issued in 1901 along with the four other awards (chemistry, physics, medicine and peace) established under the will of industrialist Alfred Nobel. Monetary reward aside, the prize undoubtedly confers considerable prestige in the world of letters - and with it a fair share of controversy.

All the same, Malmqvist says we shouldn't make too much of the award.

"It's a prize awarded by 18 people living in the very periphery of Europe, in a small country. And it's given to someone whom the majority of these 18 people agree is a very good writer," he says.

"It's not a world championship. It couldn't be."

Over the next few weeks, members of the academy whittle down a preliminary list of 20 Nobel candidates to just five. That means making a lot of tough choices to come up with the shortlist next month, before announcing the winner in October.

Bumping clenched fists against each other to illustrate the head butting that sometimes goes on behind the scenes, Malmqvist says, "the discussions can be very heated".

But he adds, "Once we have decided, we go and have a very good meal. And then we are good friends again."

Malmqvist grins. A tall man with a hearty laugh, he is remarkably fit for his age - the Swede turns 90 in June - and generally maintains a composed view of the Nobel hoopla. After 29 years on the literary panel (he was inducted into the Swedish Academy in 1985), he knows how dramas can be played out.

"Membership is for life. So you can't leave the academy," he says with a shrug.

His lifelong love of Chinese culture began in 1946 while he was studying Greek and Latin at Uppsala University in Sweden. He stumbled across , a book written in English by the Chinese linguist Lin Yutang, and was immediately piqued by the Taoist philosophy it described.

The young Malmqvist went on to read , a seminal work believed to have been written in the 6th century BC.

He found himself lost in its various translations in English, French and German, and decided he had to learn Chinese to properly understand the text. He moved to Stockholm to study Chinese language and literature under renowned sinologist Bernhard Karlgren.

In 1948, he made his first trip to China, thanks to a Rockefeller fellowship to study dialects in Sichuan; travelling by ferry and plane, the journey from Gothenburg took two whole months.

This first visit proved life-changing. He met his first wife Chen Ningtsu in Chengdu, and they spent half a century living and studying together before she died in the 1990s.

A sojourn on Mount Emei during this period also made a profound impression. Today, he still relishes the seven months he spent at a Buddhist monastery, learning classical Chinese literature from an educated monk, surrounded by a serene landscape.

"There were no tourists. It was really quiet," he says slowly, as if reciting a poem. "The only noise was the crickets and the birds singing."

Is his affection for this rural experience reflected in his taste in literature? "Yes," he admits, "the countryside and the unsophisticated Chinese people, whom I met in those villages. It's simple life that I really enjoy."

Even all those decades ago Hong Kong was far too busy for Malmqvist.

"There were too many people and it was too noisy," he says of his brief stop in Hong Kong in 1950. Returning to Sweden after his marriage, he and his new wife had to make a stop in the city en route and spent a honeymoon of sorts on Lantau.

"I rented a stone hut on the peak of Lantau island, and stayed there for several months."

In the following decades, except for a two-year stint in the late 1950s as Sweden's cultural attaché in Peking (he still likes to refer to the capital by its old name), Malmqvist has established himself as a sinologist and taught Chinese literature and linguistics at the University of London, Australian National University in Canberra, and Stockholm University.

He "dabbled" in translation, too. Malmqvist has published more than 50 Swedish translations of Chinese literary works, including collections of poetry from the Han, Tang and Song periods, Taoist classic and two of China's four great classical novels - and .

Translation plays a critical role in promoting world literature, Malmqvist says, especially in bringing a writer's work to a readership beyond his or her home country. "A former secretary of the Swedish Academy once said: 'World literature is translation.' I think this is a very important statement."

That's why he believes sinologists should not only engage in academic research but also in translation; and for himself: "It's to allow people from my country to appreciate the Chinese literature I like."

Unfortunately, he says, there are as many poor translators as there are good writers in China.

"What makes me angry, really angry," he cries, eyes blazing, "is when an excellent piece of Chinese literature is badly translated. It's better not to translate it than have it badly translated. That is an unforgivable offence to any author. It should be stopped.

"Often translations are done by incompetent translators who happen to know English, or German, or French. But a lot of them have no interest and no competence in literature. That is a great pity."

There are notable exceptions such as the late British sinologist David Hawkes' rendition of Cao Xueqin's epic novel , which he regards as a rare gem of translated Chinese literature.

Malmqvist also translated works by modern Chinese writers such as Ai Qing, Lu Xun, Wen Yiduo and Shen Congwen. Of Shen, he says: "If he hadn't passed away, he would have got the Nobel Prize in 1988."

In the 1980s, he began to translate contemporary works by Bei Dao and Gu Cheng, Taiwanese poetry, and works by Gao Xingjian and Mo Yan.

It's natural to think that Gao and Mo beat other prominent Chinese authors because they happen to be the sinologist's favourites.

But even though he concedes that the Swedish Academy's choice of the literary prize-winner is largely subjective, Malmqvist insists that the literary value of a writer's oeuvre is the sole criterion for awarding the Nobel Prize, and geopolitics is never a consideration.

"The prize is given to a writer, not to a country. Before Gao received the prize, a journalist from Peking asked me: 'How is it that China, with its 5,000 years of glorious history, never got the prize, but poor little Iceland has?' I said: 'Iceland hasn't got the prize, but an Icelandic writer has got the prize.'"