Lyricist James Wong's legacy goes digital with the launch of website

Ten years after the death of Canto-pop lyricist and man of letters James Wong Jim, a website has been launched tracing his legacy in the golden years of Hong Kong's popular culture, writes Elaine Yau

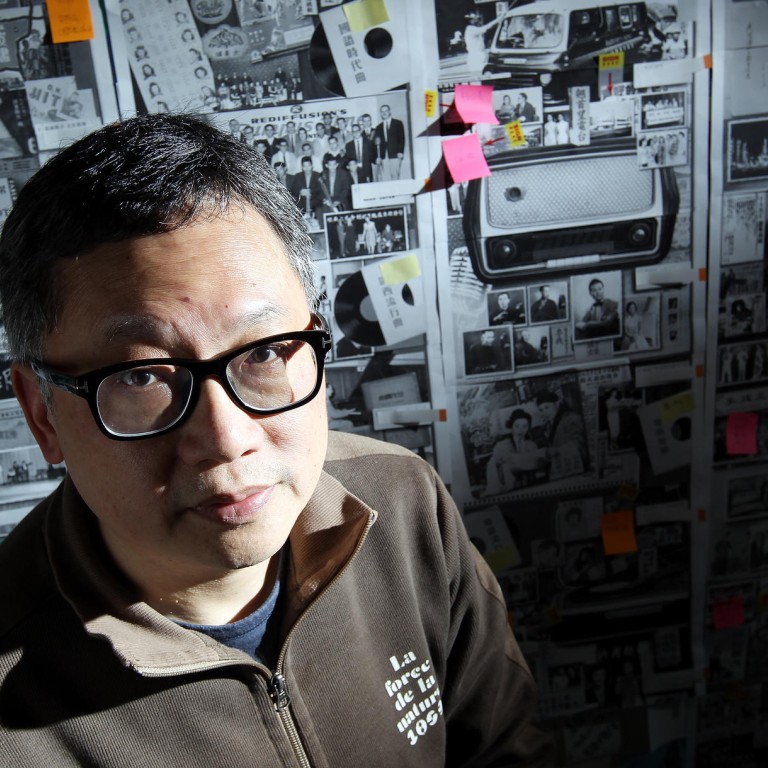

There is no doubt quite a few pop fans envy Ng Chun-hung's job. As a sociologist studying popular culture in Hong Kong, Ng's research often puts him up close and personal with Canto-pop luminaries such as Sam Hui Koon-kit, a pioneering singer-songwriter who became the subject of a book by Ng.

Ng's latest project is on the legacy of the late lyricist James Wong Jim and traces the development of local identity and culture. The culmination of eight years' work is presented on James Wong Stories, a website that Ng launched last week.

Despite being derided for its crass commercialism and lack of depth, pop culture offers a good way to tap into the zeitgeist, Ng says.

"It captures the unvarnished feelings and thoughts of the masses in a particular age. If you want to know what people in the '50s were like, instead of asking history experts, you should find out what songs were the most popular then," he says.

Most of all, he was an enormously prolific lyricist and collaborated with composer Joseph Koo Ka-fai to produce a slew of movie and television theme songs that became hits across Southeast Asia during the '70s and '80s. His extensive experience in the entertainment business also provided rich material for his thesis on the rise and fall of Canto-pop when he pursued a PhD at Chinese University in the late '90s.

Wong attended some of Ng's classes out of interest, and the pair got to know each other well.

After Wong died of lung cancer in 2004, his family asked Ng to help organise the body of work and personal effects that he left behind. The following year Ng pulled together material from Wong's school days for a memorial exhibition at the University of Hong Kong.

It was only later that the serious stock-taking began.

"Wong was a man of letters, writing lyrics, detective fiction and newspaper columns, advertising slogans and books. So most of the records are text based. His 1,000 sq ft home was filled with thousands of books," Ng says. "The book collection was encyclopedic. It covered philosophy, cultural studies, Chinese literature, music theory, drama writing and, of course, pornography."

Wong also had the most complete collection of the writings of Bertrand Russell that Ng had encountered outside of libraries.

"Although he worked in entertainment, he was a scholar and thorough researcher. The notes he wrote on books sometimes ran as long as the actual text," Ng says.

"As a researcher, that gives me a vast repository to fall back on in discovering who James Wong really is," Ng says. "I feel like his notes, which come up to several million words, are like oral records left by people for posterity. He writes about the inspiration for his work, how he feels when creating advertising slogans, and kept copies of all his newspaper columns."

Wong was eight when his family fled to Hong Kong in 1949 as the communists seized power on the mainland. They settled in Sham Shui Po, and he grew up in a world with few boundaries. There weren't as many exams at school and little pressure to join in extracurricular activities. All the same, he was a lively child and picked up different skills, such as swimming, acting and singing, for fun.

He learned the harmonica from a teacher who was also a renowned musician, and began recording music in a studio at the age of 13. That brought him into contact with all the big stars of the time, like Cantonese opera doyenne Hung Sin-nui, Ng says. "Showbiz glamour had been part of his life since his teens. By the time he went into advertising in his early 20s, he had 10 years of experience in the pop music business."

Wong also loved to read and was like "a sponge absorbing all those gems of Chinese literature. When he turned to writing lyrics later in life, all he had to do was tap into his vast fount of knowledge. Creative sparks flashed as he took pen to paper," Ng says.

The researcher was particularly struck by Wong's ability to transcend a spectrum of interests. "From Chinese literature, music and sports to pornographic books, he dabbled in everything. He often spewed foul language, yet was able to write the most elegant prose in classical Chinese."

He famously took 25 minutes to come up with lyrics for the theme song for the eponymous 1980 television series, which became an enormous hit in the region.

"Joseph Koo finished penning the melody at about 1am and called Wong, humming the melody to him over the phone; Wong finished the lyrics that night in time for singer Frances Yip Lai-yee to record it in the studio the next morning. This was how the pop industry worked. It all came together at the last minute," Ng says.

The garrulous Wong would enter into debates with readers of his newspaper columns, sometimes over arcane details about the use of classical Chinese. Driven by a deep sense of curiosity, he often went to great trouble to find answers to even the tiniest questions.

Ng attributes the more flexible education system of the past with nurturing talents like Wong and Hui.

"Wong studied at La Salle College. It was an elite school, but students enjoyed a lot of freedom and were not compelled to join many extracurricular activities like today, and teachers did not simply do things by the book. If Wong was born today, he would have been very unhappy."

Many Hongkongers feel nostalgic about the past glory of Hong Kong pop and mourn the loss of stars such as Anita Mui Yim-fong and Leslie Cheung Kwok-wing, but Ng argues the decline of the local music industry simply reflected the market.

"Before 1993, the local music industry was on a roll. Concerts were packed and album sales kept going up. Music companies had plenty of resources and could afford to be bold and try out different styles and singers. But after the market began to shrink, companies turned conservative and stuck to formulaic material that was more likely to yield profits. That's why the pop scene has stagnated and keeps churning out generic pop stars. Theirs are packaged performances with none of the unique style of the Canto-pop stars of the past."

However, the emergence of idiosyncratic talents such as Eason Chan Yik-shun encourages Ng to believe there's hope yet.

"In his PhD thesis, Wong wrote that it is not fair to assume that the music of the past is better - each generation has its own voice. Hip hop strikes a chord with young people nowadays, but you can't say it lacks style or musical merit."

Ng takes an even more positive view of Hong Kong cinema.

"Film production has shrunk from 270 movies a year in 1993 to about 50 currently. But the quality and techniques have improved a lot. In the '80s and '90s, there were many more theatre chains which had screens to fill. Many movies shown then were just rubbish. In today's market, only better quality projects can secure enough resources to get made, so the audience gets to enjoy better movies than before."