Modern Western art curator Paul Moorhouse tells how he was won over by contemporary Chinese works

Western art expert Paul Moorhouse has been won over by contemporary Chinese works, writesFionnuala McHugh

Paul Moorhouse is a curator at London's National Portrait Gallery (NPG). As you'd expect, images of various individuals hang on his office walls. At the moment, these include black-and-white photos by Geoffrey Malins of soldiers in the first world war who are featured in the NPG's current exhibition "The Great War in Portraits" (which continues until June 15), curated by Moorhouse. You could say they're his professional face, the most obvious aspect of a recent career which has included organising an exhibition of the Queen's portraits.

Other photos in the room, however - of Bridget Riley, Anthony Caro, Bert Irvin - have more personal relevance. Moorhouse has had a long association with, and intellectual passion for, modern Western artists.

Art is a language. It has to convey significance otherwise it's just furniture or decoration

"I was at the Tate for 19 years," he says. When he left, in 2005, he was its acting head of contemporary art. International 20th-century art, particularly abstraction, is his speciality ("my other life"), and it is in that role that he has found himself unexpectedly feeling his way into a third arena - modern Chinese art.

The tale of how he got there shows how abstract notions can end up becoming concrete reality in the fevered art world of the 21st-century. "I was sitting in my office one day in 2010," he says, "when I had a phone call from Philip Dodd." Dodd is a former director of London's Institute of Contemporary Arts and a director of the China Art Foundation. He told Moorhouse that the Hong Kong gallery owner Pearl Lam wanted to get in touch with him "as part of her mission to have a dialogue between East and West".

His ignorance of China combined with the depth of his Western knowledge was the point. Lam already had Chinese experts; what she needed was a fresh eye with Western credentials.

Lam was organising an exhibition of seven Chinese contemporary abstract artists, which was to be called "Mindmap". However, it was Moorhouse who needed to find his way round an unknown landscape.

"I felt the ground was opening up beneath me, it was all a shock," he says, of his arrival in Beijing.

"I had lots of moments when I didn't know if a Western mind could penetrate it. There was no induction, no orientation and it started immediately - I got off the plane and went to see [the artist] Zhang Jianjun. Then, in a peculiar way, I was back in my comfort zone. The one thing I've been doing for 30 years is talking to artists."

He had an interpreter, of course, something he was accustomed to from working with the German artist Gerhard Richter. He asked everyone a lot of questions.

As any journalist can testify, however, artists, whatever their nationality, usually hate being asked what their work means. "Art is a language," states Moorhouse, whose first degree was in English and philosophy. "It has to convey significance otherwise it's just furniture or decoration. Richter is philosophical, Riley is philosophical. There are the technical aspects but that comes later."

His worry was that he was going to be confronted with "a watered-down version of Western modernism". Was he also concerned he might be used simply to provide an imprimatur for a commercial gallery?

"I was aware of that," he replies. "If I hadn't felt confident, I'd have pushed back and walked away. At the end of the initial process, I felt that the work was not only impressive, but it was giving something I couldn't find in the West. The two artists I've worked with since - Zhu Jinshi and Su Xiaobai - I respect enormously."

Last year, Moorhouse curated the work of Zhu for another Lam exhibition, "The Reality of Paint"; and this week Su has a solo show at Lam's gallery curated by Moorhouse, which will open - no great coincidence - in time for Art Basel Hong Kong.

"This is an insistently abstract artist," he says of Zhu. "There's an imperative, an exclusive forcefulness, to work in a non-figurative way with extreme emphasis on the fabric alone. For some Western artists, the abstraction is quieter but with him, it's the force of a brick wall. We think Frank Auerbach and [Leon] Kossoff use thick paint, but Zhu Jinshi makes that look like watercolour."

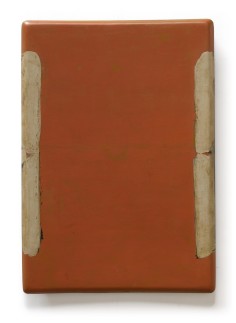

In Su's studio in Shanghai, Moorhouse viewed the pure, lacquer paintings in small chambers: "My method is to get onto an artist's wavelength. I monitor what's happening to me, and I literally see the world in a different way. When I'm with Bridget [Riley], I'm suddenly very aware of the horizon. With Anthony Caro, I'm aware of the way the world fits together. With John Gibbons, it's about rooms and niches.

"I talked to Su Xiaobai for a long time, and I said that I had a strong sense his work is connected to presence, that it's about the essence of being." He asked his interpreter to define one word Su constantly used to describe his work. "She said, 'It simply means that which exists'."

Zhu and Su both lived in Germany for many years from the mid-1980s; Su was actually taught by Richter. They've tasted far more of Europe than their curator knows of China. Yet in a few years the experience has obviously affected Moorhouse. One gets the impression, in his London office, that he's delighted to talk about this other life with a Hong Kong visitor.

"It's changed me completely!" he cries. His academic side makes him pause for a second ("I must not distort history") before continuing, "But I'd been increasingly immersed in philosophy. I'd been reading about Buddhism and Zen, and I'd reached the point of stepping outside Western tradition. And then Pearl arrived and I accepted that as a pure Zen proposition."

How has it been, returning to his Western abstract artists? "I don't think my involvement in Chinese art has changed the way I see, say, Bridget Riley's work. It's enriched it. The range has expanded."

And has the curator purchased Chinese work for his own private collection? "I'd love to. But their prices are beyond me." Su Xiaobai: Painting and Being