Plunging comic sales in Hong Kong force artists to find a new perspective

Hong Kong has a great comics heritage but plunging sales have seen mainstream genres give way to more diverse alternatives

It's a blustery Friday evening as Typhoon Rammasun sweeps past Hong Kong, but the atmosphere inside Comix Home Base in Wan Chai is easy-going as 10 of Hong Kong and Taipei's top comic artists gather for a talk. They are there for "A Parallel Tale", an exhibition that weaves tales of the 1980s and 1990s in Hong Kong with those from across the Taiwan Strait.

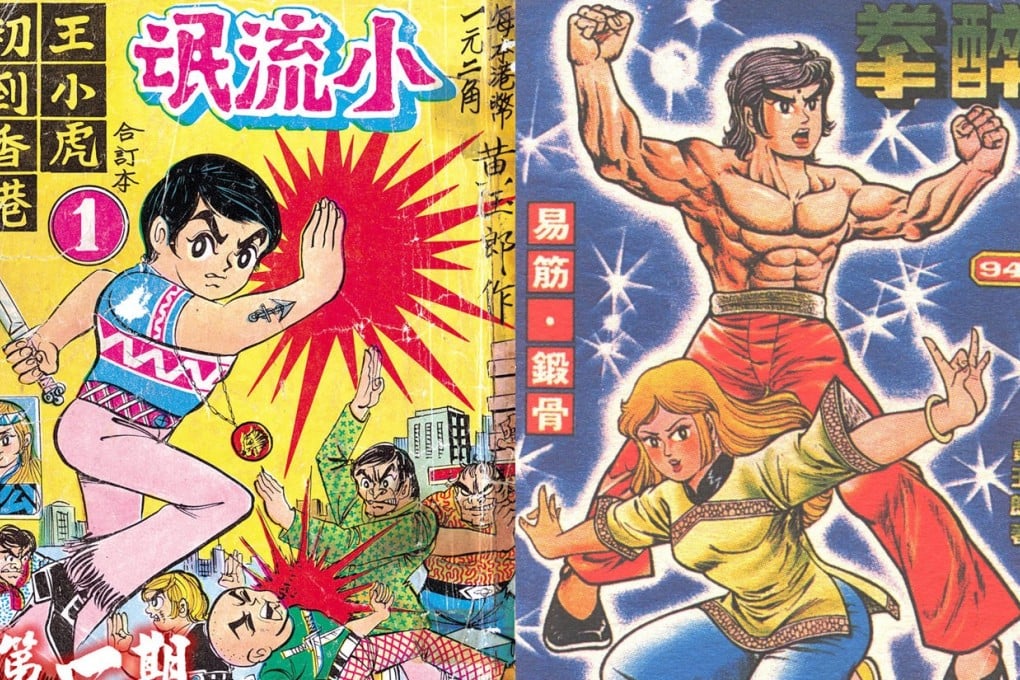

"The 1980s and '90s were interesting times for both cities," says Taiwanese comics publisher Huang Kuan-hua, opening the discussion. At the time, Hong Kong was the cultural capital of Greater China, a position that extended to comics, he says.

When a comic is successful, the opportunities are endless. Although the market is at a low point, comics have a lot of potential to transform into something new

Independent artist Ah Tui agrees: "I always looked forward to getting the Hong Kong comics when they came to Taiwan. "These imported comics were so precious."

In the world of comics, Hong Kong punches well above its weight. It's the third largest comics market in the world, after Japan and the United States, and a glance at the stack of kung fu serials on any newsstand - or the crowds lining up for this year's Ani-Com and Games fair, which runs until Tuesday - will show that it's not only an important source of entertainment, it's part of the city's cultural DNA.

Sadly, in recent years, it's a commodity that has been losing its value. Whereas action comics could once sell up to 300,000 copies, a run of 5,000 is now the norm. "It's cheaper for publishers to translate a Japanese manga than it is to invest in an original work by a Hong Kong artist," says Li Chi-tak, who launched his career in the early 1980s. The decline is not limited to Hong Kong; even Japan has seen a collapse in manga sales over the past two decades.