One of Indonesia’s most successful living artists on the burly black characters that made him a star

- I Nyoman Masriadi’s fascination with comic books, superheroes and their exaggerated physiques turned into a signature style popular with collectors

- The Bali-born artist’s paintings touch on ideas including identity, technology and materialism and mix them with sarcasm and tongue-in-cheek humour

One of the secrets to Indonesia painter I Nyoman Masriadi’s phenomenal success is being a night owl.

The Bali-born artist, whose latest artwork is currently on show at Art Basel Hong Kong (ending today), likes to paint his huge bold canvases – often featuring black, impossibly muscled figures that have become his signature – in the still of night, while everyone else is asleep.

“It’s nice and cool and there is total silence: no distractions,” he says with a smile, looking slightly embarrassed to be talking about himself. “That’s the time when I feel I work best. I don’t have to go anywhere, either. I work in the bedroom – the painting’s right next to my bed.”

The artist, 45, saw one of his paintings sell at auction for HK$7.82 million in 2008 – hitting the magic US$1 million mark – which at the time was the highest price paid for an artwork by a living Southeast Asian artist.

Masriadi, whose father earned a living as a wood carver, has continued his childhood fascination with comic books, superheroes and their powerful, exaggerated physiques – which sparked his fertile imagination and helped inspire his works’ distinctive characters – into adulthood. So, too, has he maintained a devotion to video games.

“After school I’d often go to the local shop and buy a comic … only one at a time. Now my passion is playing computer games. So, when I wake up at night the first thing I do is play on my computer. After that, I’ll start to paint.” This near-obsession for video games inspired the self-portrait, No More Game, of the weary artist, head back, slumped in a chair in his study.

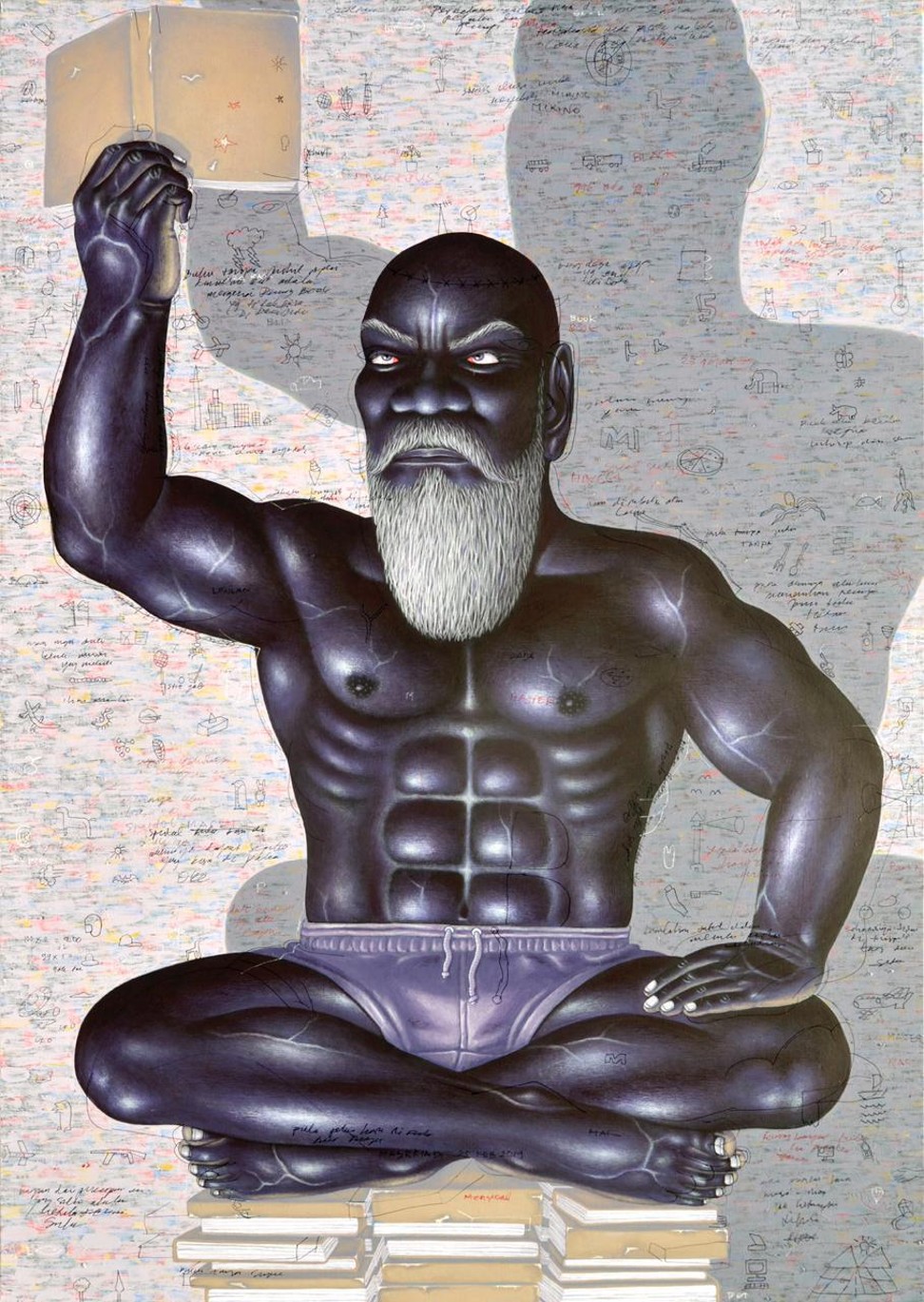

We are chatting beside the swimming pool in the garden of his spacious home in a leafy suburb of Yogyakarta, a city known for its strong art and craft heritage on Indonesia’s Java Island. A huge wooden crate, containing his new painting Untitled Book, stands in the hall, just outside his bedroom door. It is waiting to be shipped to Hong Kong for display at the five-day Art Basel fair, in the booth of art gallery Sullivan+Strumpf.

The painting had been bought by a collector on the basis of a photograph even before it left his home. It is one of about six Masriadi produces each year and took roughly a month and a half to complete.

“It takes time for all the ideas to come together – sometimes [because] I’m doing something else, such as playing the computer.”

The bold painting, measuring nearly two metres high, shows a bald, black-skinned “old master” with a white beard, dressed only in a small pair of shorts. Caught in a powerful spotlight, his vein-bulging physique shines like a sculpture and casts a shadow on the graffiti-scrawled wall behind him as he sits crossed-legged on a pile of books, holding aloft the untitled book of the painting’s name.

The shape and features of his face and ears – but not the physique – resemble those of the slightly built Masriadi, but “No”, he says with a smile, “it’s not me.”

The artist normally sleeps during the day, from 9am – after his four-year-old daughter, C Matahari, has left home for preschool – until 3pm.

“She’s the only one [in the family] interested in art and painting,” he says, and now he’s beaming. “But she doesn’t like to show me what she’s done.”

C Matahari is featured in one of his most personal artworks, titled Do Do Do – from the lyrics of her favourite children’s song, Baby Shark. With dark-tanned features, eyes hidden behind sunglasses, she is depicted holding on to a round, shark-shaped balloon.

Masriadi’s bold, figurative paintings touch on a variety of ideas – whatever comes to his mind at the time – including behaviour, identity, power dynamics, technology, materialism and masculinity. These universal themes are always accessible, combined with touches of Masriadi’s sarcasm and tongue-in-cheek humour – elements that have helped him to make his name and set his work apart from his many imitators.

One simple, witty and eye-catching piece, Juling (“Cross-eye”), sold by Sotheby’s Hong Kong in April 2011 for HK$3.8 million (US$485,000), features a familiar scene. It focuses on the faces of a crowd of mobile-phone-obsessed men and women, all of whom are staring intently at their screens – and are cross-eyed.

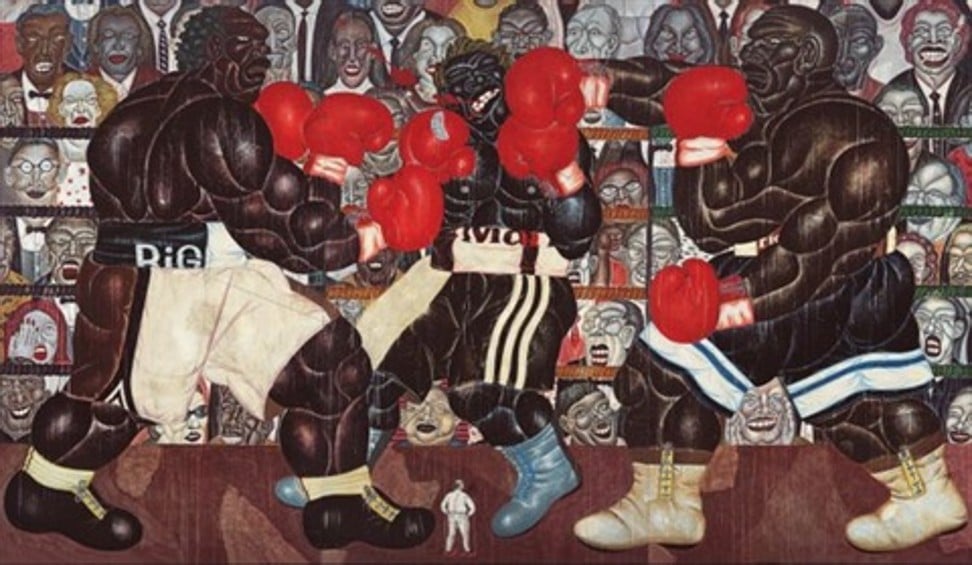

Masriadi’s works also make regular reference to his beloved comic book characters and video games, as well as boxing – he was an avowed fan of the young, “unstoppable” Mike Tyson – and stories from Balinese mythology. But he says he prefers to keep an open mind and take inspiration from what he sees going on around him.

Masriadi left the resort island of Bali to study at the highly regarded Indonesian Institute of the Arts, Yogyakarta, where most of his work involved completing course assignments. But he was keen to experiment with various styles and ways of painting the human form, including a period in the 1990s when, inspired by Pablo Picasso’s work, he tried his hand at neo-cubism.

While he was a student he sold his art works to tourists in Bali and Yogyakarta – sometimes for little more than US$10.

The fall of the dictator General Suharto in 1998 led to a shift within Indonesia’s art community away from traditional, conservative expressionist paintings. Masriadi began to focus more on figures – often with exaggerated physiques.

He began to sell his work regularly to local galleries and prominent collectors, and some of his work featured at auctions in Hong Kong.

Art Basel Hong Kong: female artists take back power

It was at Christie’s Hong Kong auction in May 2007 that people started to take particular notice of his work. An experimental 1998 neo-cubist painting, Angels, sold for HK$240,000 – more than seven times the top estimate of HK$32,000. But it was another work, Dance, portraying three black-skinned figures dancing in unison with their arms linked, from 1999 – the year he felt he had developed his own distinctive style – that really resonated with art collectors. It sold for HK$540,000 – more than 10 times the highest estimated value of HK$50,000.

Interest in Masriadi’s work reached fever pitch by May 24 the following year. That was when Christie’s sold another painting, the tongue-in-cheek Used to Being Stripped – of a powerfully built black man in handcuffs with a pair of pink women’s panties around his ankles – for HK$4.2 million, more than 10 times its highest estimated value of HK$380,000.

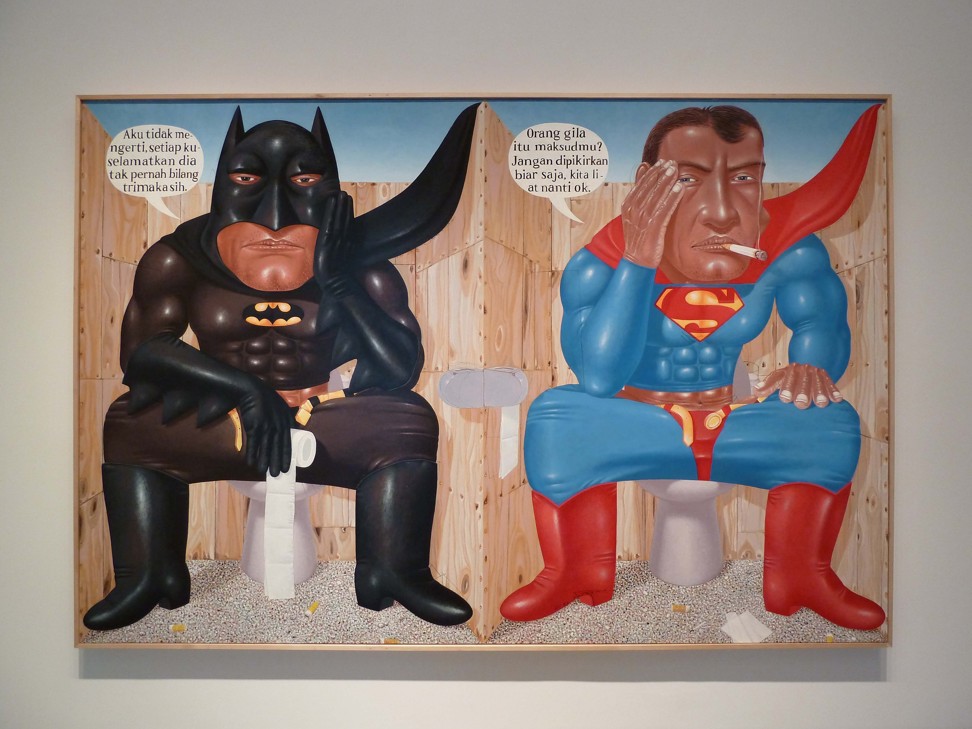

The Sotheby’s Hong Kong auction of October 4, 2008, saw Sorry Hero, I Forgot – showing Batman and Superman sitting in two adjoining toilet cubicles discussing frustrations about being superheroes – sold for HK$4.82 million.

Two days later, Masriadi’s The Man From Bantul (The Final Round) from 2000 achieved his record-breaking sale of HK$7.82 million. A powerful allegory of Indonesian politics, the painting shows three huge, impossibly muscled black boxers in a ring, two of whom have three arms and are teaming up on the other fighter, who is spitting blood after being pommelled in the head.

Yet the artist received nothing from that sale – having sold the painting to a collector years earlier for about US$250.

Continued strong interest in his work, which led to exhibitions in Singapore and the United States, saw Dance back at a Christie’s auction in May 2013 – selling this time for HK$3.27 million, six times what it achieved in 2007.

Why China’s art collectors aren’t spending like they used to

Tragedy, from 2010, was inspired by another of Masriadi’s favourite activities – smoking – and his attempts to quit the habit dating from his student days. The painting, sold after being exhibited in New York, features a wide-eyed, bare-chested black man puffing on five lit cigarettes at once as he stands over a huge pile of discarded cigarette butts, while flames escape from his outstretched fingers.

Masriadi’s efforts to quit have clearly been unsuccessful as he stubs out the last of two cigarettes in an ashtray and stands up. It’s 4.30pm on a Sunday and his usual pattern has changed.

“I’m sorry, but I need to get some sleep now,” he says, smiling as he shakes hands, then wanders off past the crate and shuts the bedroom door behind him.

‘Untitled Book’ by I Nyoman Masriadi will be on display at Sullivan+Strumpf, Art Basel Hong Kong 2019, Booth 3C23, Galleries Section, Hong Kong Convention and Exhibition Centre, Wan Chai, until Sunday March 29.