Qing dynasty scientific instruments on show in Hong Kong

Western inventions in fields such as astronomy, mathematics and medicine, loaned by Beijing's Palace Museum, among those on display in interactive Science Museum exhibition

At first glance, the painting bathed in soft golden light hanging in the centre of the gallery at the Hong Kong Science Museum appears to be just another depiction of the Forbidden City. But closer examination reveals its true importance, making it an integral piece of the museum's new exhibition, "Western Scientific Instruments in the Qing Court".

Commissioned by Emperor Qianlong (1735-1796), the painting illustrates foreign envoys bringing tributes to the Qing court. Distinctly different from the Chinese men detailed in the painting, the foreigners, hailing from places such as Europe and Japan, are identified by their dress and by banners declaring where they come from. This image represents the exhibit's raison d'être: to tell the story of the bond between East and West, fostered by a mutual interest in scientific advancement and strengthened by a merging of cultures.

As early as the Marco Polo era (13th-14th century), foreign missionaries flocked to China to spread Western beliefs and ideals, which included thoughts about science and medicine. They brought with them samples of European technology, some of which are displayed in this exhibition and span a variety of categories such as astronomy, mathematics, medicine, weaponry and horology.

Emperor Kangxi (1662-1722) encouraged and fostered the exchange of ideas between China and Europe as he took a personal interest in the instruments that were presented to the Qing court, says the exhibit's curator, Paulina Chan Shuk-man.

"In the past, China was very conservative," she says. "Europeans brought innovative ideas and more liberal thinking into the country."

The exhibition boasts more than 120 artefacts on loan from the Palace Museum that were collected or made by the Qing court during this period of exchange. Most of the items were assembled during the decades of Emperor Kangxi's reign, says Hong Kong Science Museum director Karen Sit Man.

"It shows how important science is to the development of society, and how the personal interest of an emperor really influenced the development of science in the Qing period," says Sit.

Many of the artefacts enhanced China's knowledge of the natural world and influenced daily life, says Chan. The items on show were selected based on how well they represent the message of the exhibition and their scientific value, says Sit.

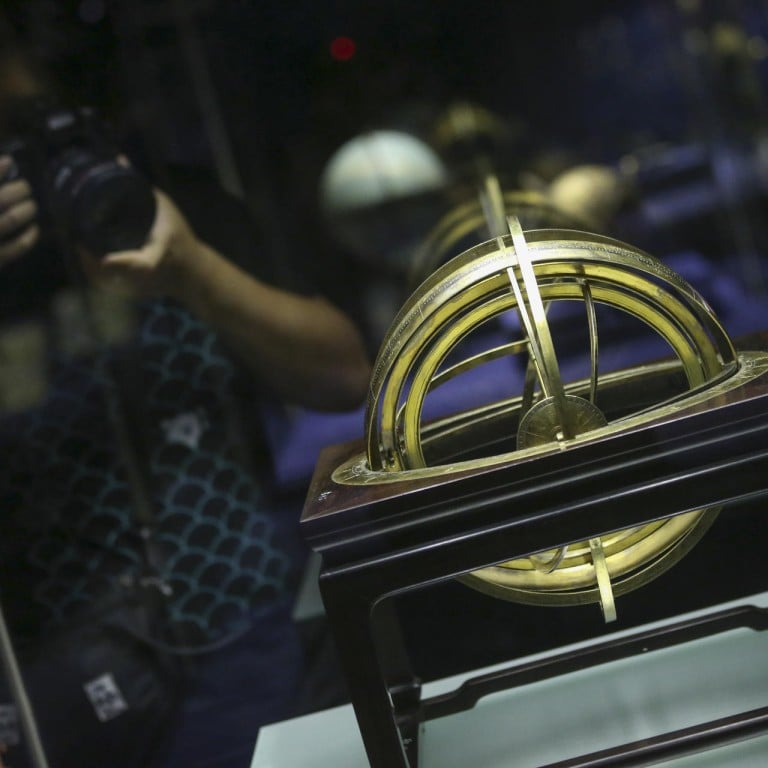

As the Chinese were dependent on the stars for deciding their fate, astronomy tools were of special importance. European inventions such as an armillary sphere helped Chinese astronomers better understand how the sun and moon orbit the earth.

The sphere on show was made by Ferdinand Verbiest, a Flemish missionary whose knowledge of astronomy and mathematics allowed him to make improvements to the Chinese calendar. He befriended Emperor Kangxi and was made head of the Qing court mathematical board and director of the observatory.

Emperor Kangxi's interest in science led him to invite more missionaries to China. He was particularly interested in mathematics, thus encouraging more foreigners with expertise in numbers to visit. These mathematically minded missionaries brought with them the innovative idea of a mechanical calculator.

First invented in 1642 by French scientist Blaise Pascal, the calculator performs addition and subtraction using a system of complicated gears and the so-called nines' complement. By the 18th century, the Qing court had begun to produce similar calculators, according to exhibition notes.

WATCH an explanation of how Pascal's machine works, by MechanicalComputing

This trading of ideas and knowledge also spread to medicine as Westerners began influencing traditional Chinese medicine with medical and anatomical journals.

In the latter half of the 19th century, instruments such as a human anatomy model were introduced. Made of oil painted paper, the model has removable parts and offers an accurate depiction of muscle tissue and blood vessels. This model, along with other instruments such as stethoscopes and sphygmomanometers (for measuring blood pressure), advanced Chinese medicine by increasing knowledge of the body's inner workings.

In addition to instruments of learning, the merging of ideas led to the introduction of European technology such as weapons and clocks. According to museum research, Emperor Kangxi's iron gun was manufactured in the Qing court, but it incorporates Western elements such as the flintlock and matchlock firing mechanisms.

Ornate and scientifically complex clocks were also brought during this time, representing a fusion of art and technology. This is best illustrated by a French metal clock with a barometer and thermometer that utilises a piston wheel.

As a result of the scientific exchanges, cultural connections multiplied, with missionaries bringing bicycles, mutoscopes (an early motion picture device) and gramophones to the Qing court. The mutoscope introduced a staple of Western countries to China: movies. By feeding film into the machine and cranking its handle, people could view the moving picture through a glass.

As a result of the increasing acceptance and interest in Western culture, missionaries were eager to learn Chinese and their grasp of the language allowed them to become more familiar with Chinese customs, says Chan.

The exhibition combines static and interactive elements. According to Sit, interaction is important for visitors to truly understand the science behind the exhibition.

"For this exhibition we realised that most of the pieces are in showcases and it's quite difficult to really understand the principles without playing with them," says Sit. "So we've developed some interactive games and put some models on display to let visitors, especially the children, play with them so they can understand why these instruments were important. And hopefully they will develop more interest in history."

Part of the Hong Kong Jockey Club Series, the exhibition is one of the first joint projects in a five-year agreement between the Leisure and Cultural Services Department and the Palace Museum.

In the past, China was very conservative. Europeans brought innovative ideas and more liberal thinking into the country

By combining past and present, this show is unlike any the Hong Kong Science Museum has undertaken, says Sit.

"In this exhibition we have the real objects, the cultural relics and artefacts," she says. "We try to interpret the science through these artefacts. Most other exhibits at the museum are built to showcase scientific principles."

A collaboration between a science museum and a museum most known for historical artworks did raise concerns for organisers of the exhibition, says Sit. However, the Palace Museum has more than just paintings collected by the Qing court, says the museum's director, Shan Jixiang.

"The Palace Museum owns a great number of pieces from all over the world," says Shan. "Most of the collections come from the cultural exchange in the period of 'all nations coming to court', which we now refer to as 'One Belt, One Road'."

Chan adds: "Most of the people in Hong Kong think that history is a rather boring subject, but we don't. We created multimedia and interactive elements to give more life to the objects. Every object has a story, and we want to tell that story to the public."

"Western Scientific Instruments in the Qing Court", Hong Kong Science Museum, 2 Science Museum Rd, Tsim Sha Tsui East. Inquiries: 2732 3232. Ends Sept 23