Underneath the colours

Biography adopts imaginative approach to add zest to Cezanne's somewhat uneventful life, writes Julian Bell

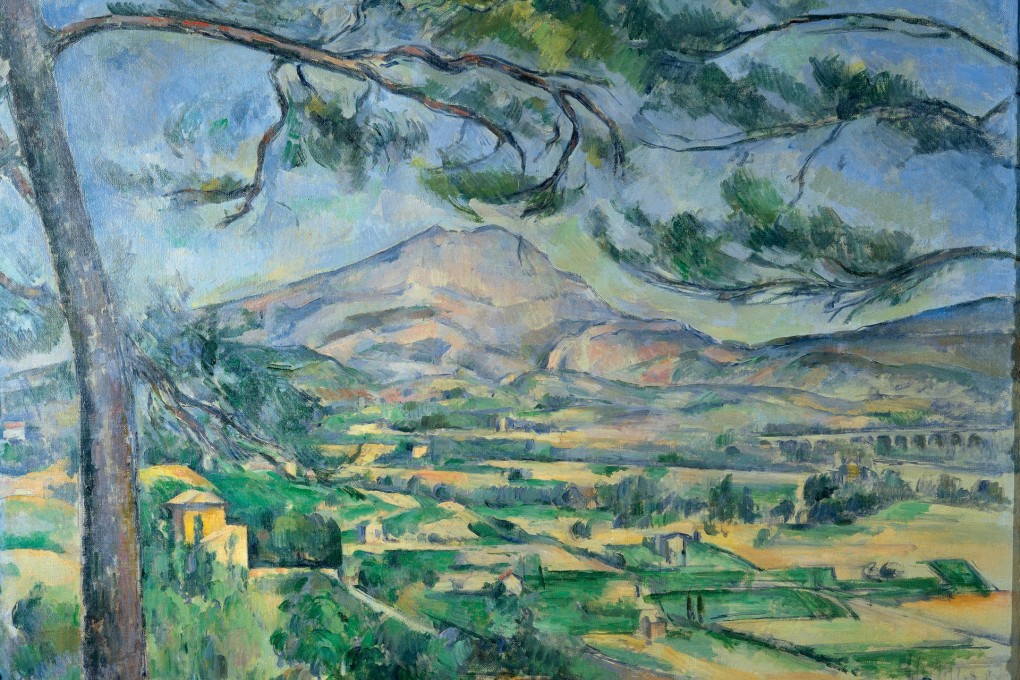

Paul Cezanne demands of us. Like no one else's, his paintings push and pull at our vision. His mountains seen through trees and his tabletops of apples upset our notions of "here" and of "there", of light, matter and distance: what constitutes a feeling and what an object get radically spun about. Cezanne's art is giddying and heady, a charge of magnetic energy sent through shapes and colours to regroup them in strange new harmonies: the world looks different as you walk away.

Allen Ginsberg, quoted in Alex Danchev's new biography, Cezanne: A Life, describes its effects as "eyeball kicks". Although this painter was a school of one, resembling no one else, few painters could work the same way again after taking in what he had been doing. Here is the man who more than any other set 20th-century painting on its course.

And yet this messiah of modernism has always - from his youth in the 1860s, down to the present - appeared a misfit. If his way of representing things is strong, on certain levels it also seems wrong. This is not the world we normally move about in, it's some alternative plane of experience made solely possible by paint. To reach for it, so people have thought, Cezanne must have been in the grip of an obsession - some disturbance, some malfunction.

Such reactions came not only from casual observers confused by his boorish manners and dismayed that he didn't draw "straight". It was Cezanne that Emile Zola, his old school friend from Aix-en-Provence, had largely in mind when he wrote a novel about an artist doomed to failure by "heroic madness" and defective vision. In fact the cues for this could have come from Cezanne himself. "I am a primitive, I have a lazy eye," he would protest in his later years. He was afflicted by "brain trouble" and was "no longer my own master".

Danchev's new life - original, engaging and highly persuasive - brushes aside that line in pathos, likewise refusing the "profitless psychoanalysis" that many a distinguished interpreter has applied to the artist. The problems of Cezanne, Danchev argues, were of his own conscious choosing. The ambitious and well read young Provencal, coming to Paris just as a new art scene was coalescing around Edouard Manet, began pretty early to stake out his own independent path.

"In the mid-1860s, at the age of about 25, Cezanne set about becoming Cezanne." Socially, that involved developing a sardonic, forbidding crust, posing as a querulous hick from the sticks. (On being introduced to the dapper maestro of modern painting: "I won't offer you my hand, Monsieur Manet, I haven't washed for a week.")