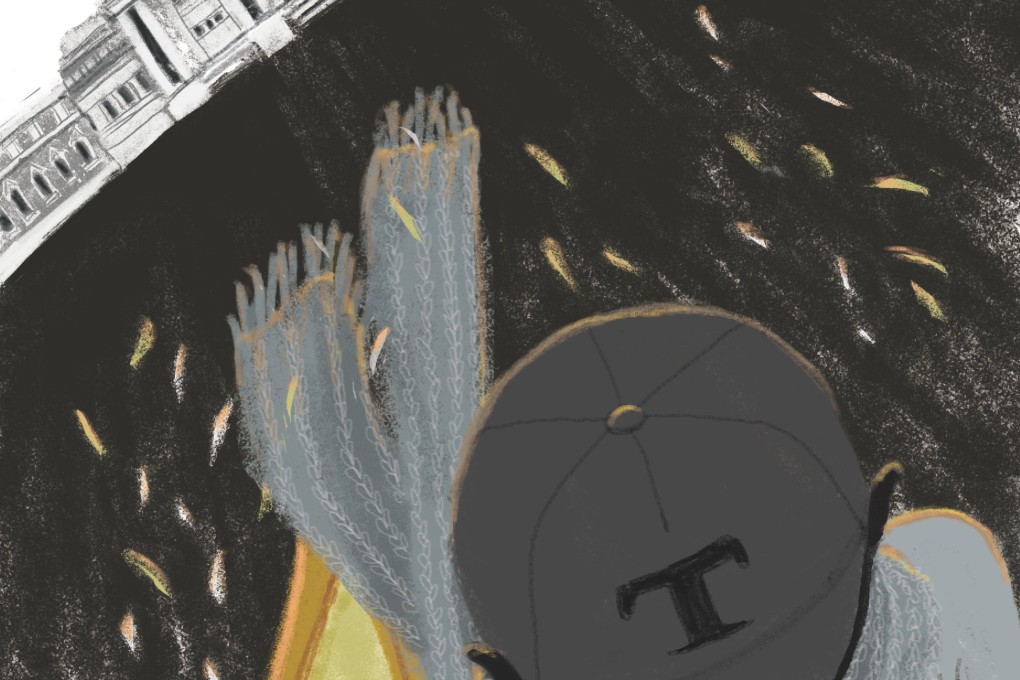

Donna Tartt's third novel flies high

Donna Tartt's third novel is solid gold in both plot and prose

The Goldfinch

by Donna Tartt

Little, Brown and Co

5 stars

Furniture restoration is perhaps not an obvious subject for one of the most keenly anticipated novels of the 21st century. But Donna Tartt has rarely traded in the obvious.

Tartt's two previous novels, the much-heralded debut The Secret History and its long-awaited successor The Little Friend, were enigmatic but eminently entertaining concoctions. Tartt could do high-mindedness (classics, American gothic) and murder mystery with equal ease.

The novel is vast at 771 pages [yet] manages to remain intensely intimate, thanks largely to Tartt's microscopic powers of description

Renovating antique forms for a modern audience offers an elegant expression of Tartt's literary approach in The Goldfinch. The theme is introduced after a series of convoluted events and encounters when our narrator, Theo Decker, meets a towering bohemian craftsman called Hobie, who lives in Greenwich Village.

Hobie takes Theo under his wing, an act of kindness he will both cherish and live to regret, and teaches him the basics of his trade. Theo is spellbound by the confusion of imitation and originality, truth and lies, old and new. Hobie teaches him that perfectionism in restoration requires flaws to be included: "Anything too worn was a dead giveaway," Theo notes. "Real age … was variable, crooked, capricious, singing here, and sullen there."

Tartt's Goldfinch attempts something similar, but does so by expanding Fabritius' canvas a few trillion per cent. Whereas the painting is modest (Fabritius' bird is no bigger than, well, a goldfinch), the novel is vast at 771 pages. Somehow, despite its scale, this extraordinary work manages to remain intensely intimate, thanks largely to Tartt's microscopic powers of description. The Goldfinch exults in using three adjectives where one might suffice. The effect in the opening pages is challenging but oddly gripping, as if fictional time has slowed to that of real life itself - an homage, perhaps, to Fabritius' goldfinch, which imitates reality in scale, shape and colour, but is irrevocably contrived.

The novel progresses by exploring how matters of a moment unfurl unpredictably over time. For 13-year-old Theo, this begins with an explosion: a terrorist bomb destroys a wing of a New York museum. The device deftly reminds us of Fabritius' own death almost four centuries before, setting in place what Theo later describes as a "dreamlike mangle of past and present". Tartt's forensic prose is intent on tracing the unforeseeable consequences of this blast - not only for the characters who were present, but those yet to appear.