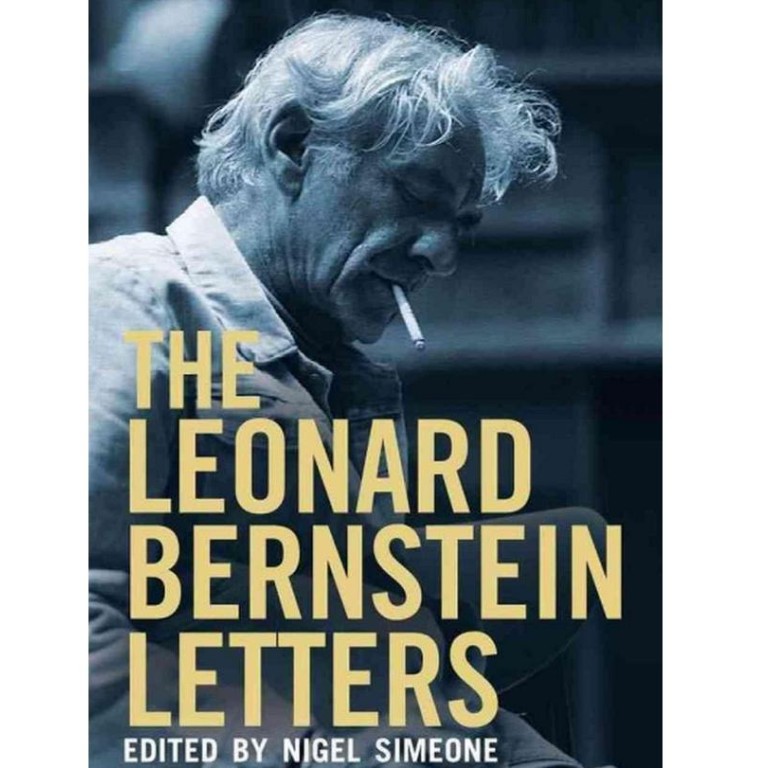

Book review: The Letters of Leonard Bernstein, edited by Nigel Simeone

"You see, I still don't really know quite what I want to do," Leonard Bernstein wrote to a friend in 1939, when he was 20 years old. "Conduct, compose, piano, produce, arrange, etc. I'm all of these and none of them." Over the next 50 years, the question was less what he would do than how he would do it all.

edited by Nigel Simeone

Yale University Press

2.5 stars

"You see, I still don't really know quite what I want to do," Leonard Bernstein wrote to a friend in 1939, when he was 20 years old. "Conduct, compose, piano, produce, arrange, etc. I'm all of these and none of them." Over the next 50 years, the question was less what he would do than how he would do it all.

One of the great personalities of the 20th century, Bernstein (1918-90) had capacious talents and an uncommonly full life. But , selected and edited by Nigel Simeone, feel overlong and curiously thin despite some dazzling pages.

The reader of these 650 letters will not discover Bernstein's feelings about his surprise smash New York Philharmonic debut in 1943. Or his thoughts about his separation from his wife, Felicia, in 1976 and '77, when he felt he could finally live openly with a man.

While there are more or less intriguing drafts of potential concert programmes, and a memorable tussle with John Cage about Bernstein's inclusion of an orchestral improvisation in a 1963 Philharmonic concert, there is, for example, no real discussion of his beloved Mahler.

His accounts of the musicians with whom he worked are just as unilluminating. "Callas is greater than ever," he writes while rehearsing Bellini's with the soprano in Milan. She "sings like a doll".

We get little sense of Bernstein, who was constantly on tour, as a profound observer of the world. "Germany and Austria were fabulous, filthy, Nazi, exciting," he writes, which may well have been true in 1948, but skims the surface nevertheless.

Janis Ian, who performed her song on a Bernstein TV special, wrote him two adorable letters - but that's about it as far as pop goes.

Jacqueline Kennedy is a more acute, articulate listener than Bernstein himself when she writes of the "sensitive trembling" of Mahler's Fifth Symphony, "this strange music of all the gods who were crying", in the book's most extraordinary letter, written at 4am on June 9, 1968, hours after Robert F. Kennedy's funeral.

is best seen as an appendix to Humphrey Burton's 1994 biography of Bernstein, a comprehensive and fair work. The letters on their own don't take us much deeper into the man - or into the culture of which he was so vital a part - than we've already gone.