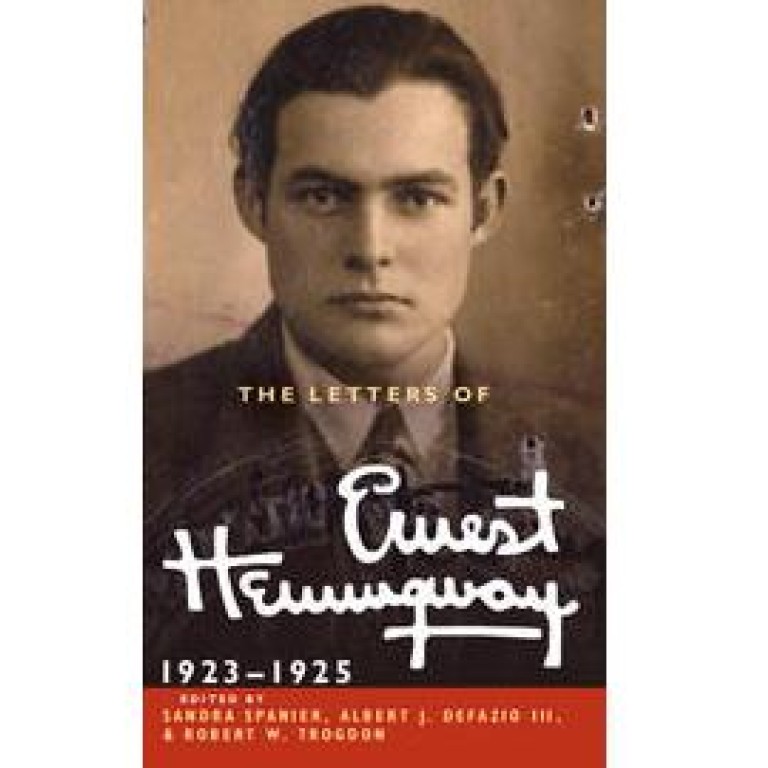

Book review: The Letters of Ernest Hemingway

For all the biographies and critical studies that have been published about Ernest Hemingway in the past 60 years or so, none has really come as close to the man as this collection of letters is now allowing.

edited by Sandra Spanier et al

Cambridge University Press

4 stars

For all the biographies and critical studies that have been published about Ernest Hemingway in the past 60 years or so, none has really come as close to the man as this collection of letters is now allowing. It's as if we are watching a picture emerge on blank paper as the developer does its darkroom magic.

"This virtual narrative produces a rather different perspective, as shifting, incomplete, and episodic as lived experience, which it mirrors more closely than a biographical account," J. Gerald Kennedy writes in the introduction.

This volume includes a mere fraction of the total cache - 242 letters, about 60 per cent of which have never been published - but it spans three of Hemingway's most significant early years.

Except for a few dreary months in Toronto when his wife, Hadley, gives birth to their son and Hemingway grows increasingly disgusted with his newspaper job at the , this is the intense Paris period when he falls under the influence of Ezra Pound and Gertrude Stein but carves out his own path to the brink of stardom. He is learning how to navigate the publishing world as well as the bull rings of Spain and the snow-clad mountains of Switzerland and Austria.

Hemingway's voice in letters is often far different than his voice in fiction - he is by turns relaxed, playful, impulsive, solicitous, boastful and indignant. He's sloppy sometimes, and his typewriter does not always work, and with the closest of friends he engages in boisterous bursts of invented and wackily bent language, at least partly influenced by the poet Pound (a job is a "jawb", a letter a "screed", and you'll have to imagine what "yencing" means, because its equivalent can't be printed here).

"Especially in letters to male friends," Kennedy writes, "we meet a coarse, unbuttoned Hemingway who flaunts his prejudices, hostilities, and resentments with sardonic vulgarity."

This should not be a surprise to anyone familiar with the ever-coarse, ever-unbuttoned and ever-complex character that the young American moulded himself into. But it's also instructive and uncomfortable to listen in as Hemingway shovels racial, anti-Semitic and anti-homosexual epithets, especially when he's buttering up Pound.

For those with a passion for American literary history and an interest in the machinery of fame, these letters provide an abundance of raw material and a few hours' worth of scintillating reading.