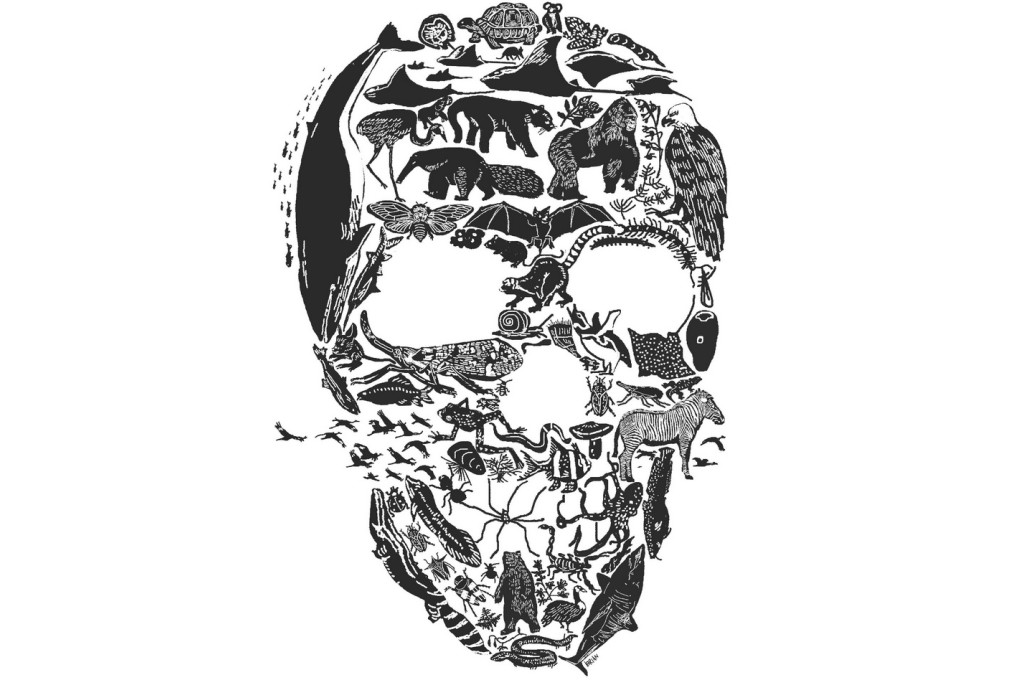

New book says humans have a say in next extinction event

A new book says it's up to us to prevent the next mass wipeout, writes Caspar Henderson

One day about 66 million years ago - it was in June or July if the evidence from fossilised pollen traces has been interpreted correctly - an asteroid somewhat larger than Manhattan ploughed into the earth near what is now Chicxulub in the Yucatan Peninsula, Mexico, at 72,000km/h.

As it hit with a force equivalent to more than 100 million megatons of TNT, or about 1,500 times the total content of the world's present nuclear arsenals, the asteroid sent a vast cloud of scalding vapour thousands of kilometres in all directions, and blasted more than 50 times its own mass of pulverised rock high into the sky where, as tiny particles, it incandesced and heated the entire atmosphere to several hundred degrees Celsius, killing almost everything unprotected by soil, rock or deep water.

A lot is uncertain. What is beyond reasonable doubt is that something big is under way

Many scientists believe that about three-quarters of animals, including the pterosaurs, the mosasaurs and, as every child now knows, the non-avian dinosaurs were wiped out as a result. It took millions of years for life to recover and surpass its previous diversity, this time with a new ensemble of species that included our distant ancestors. This event, known as the Cretaceous-Paleogene extinction, is counted as one of five mass extinctions over the past 500 million years or so, where a mass extinction is defined as an event in which a significant proportion of life is eliminated in a geologically insignificant amount of time.

At first glance, the footprint of industrialised humanity on the biosphere may look small compared with that of the Chicxulub asteroid. The additional input of heat into the world's oceans resulting from greenhouse gases put there by the combustion of fossil fuels, for example, is equivalent to only about four atomic bomb detonations. But first glances are sometimes misleading.

Or not. A lot is uncertain. What is beyond reasonable doubt is that something big is under way. The best estimates are that the earth is losing species at many times the background rate (the natural churn in which a few species go extinct every year while new ones evolve), and that 30 per cent to 50 per cent will be functionally extinct by 2050.

The plight of the non-human world has inspired many works of popular science over the past 20 years or so. A 1995 book by Richard Leakey and Roger Lewin, presciently titled The Sixth Extinction, David Quammen's The Song of the Dodo, in 1996, and numerous essays by E.O. Wilson are among those that speak with clarity and urgency.