Book explores what made Gavrilo Princip, the man who ignited the great war

Gavrilo Princip's act of violence was the spark that set off the first world war. A new tome delves into his life and motives, writes Christopher Clark

The Trigger: Hunting the Assassin Who Brough the World to War

by Tim Butcher

Chatto

4.5 stars

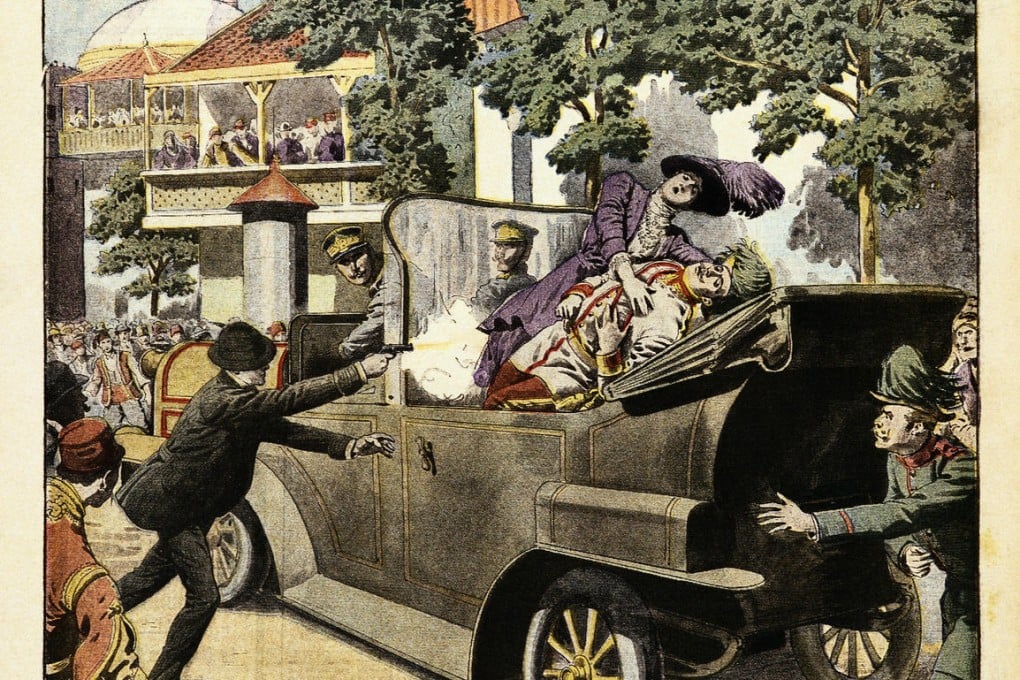

At about 10.45am on June 28, 1914, Gavrilo Princip fired twice at point-blank range into the car bearing the heir to the Austro-Hungarian throne, Archduke Franz Ferdinand, and his wife, Sophie Chotek.

The first bullet tore through the collar of Ferdinand's uniform, boring into his neck and opening his jugular vein. The second, aimed at Oskar Potiorek, the Austrian governor of Bosnia and Herzegovina, went wide, probably because members of the crowd were already trying to restrain the assassin. The bullet flew through the door of the car and was deflected into the abdomen of the archduke's wife. She was already falling into a coma as the driver reversed the car away from the scene and sped towards the governor's residence. The archduke remained conscious for long enough to address his wife with words that would soon be reported across the world: "Sophie, Sophie don't die, stay alive for our children." Within half an hour, both were dead.

We begin to see the world through Princip's eyes. These were the hills he climbed and the paths he walked

Amazingly, little is known of the then 19-year-old Bosnian Serb whose shots triggered the escalations that brought war to Europe. Princip hailed from western Bosnia, a land of harsh terrain and virtually nonexistent infrastructure, crossed by swift watercourses and closed in by mountains. These are the backwoods of the western Balkans, the vukojebina, the land, to use a colourful local expression, "where the wolves f***". The story of how Princip left his home, of his journey from model schoolboy to disaffected teenager, militant nationalist and political assassin, has remained in shadow partly because the paper trail is so meagre, and partly because his biography, located at one of the inflection points of world history, has been warped from the beginning by the forces his action helped to unleash.

In this book, a masterpiece of historical empathy and evocation, Tim Butcher goes in search of the person behind the myths. Like Ernest Renan, the biographer of Jesus who roamed the valleys and villages of 19th-century Galilee in search of clues to the boyhood and family life of his subject, Butcher acquaints himself with Princip by walking in the young man's footsteps from his birthplace in the tiny hamlet of Obljaj in western Bosnia to Sarajevo and across the border to Belgrade, the capital city of neighbouring Serbia. What results is an extraordinary journey through landscapes and communities harrowed by history.

Only when Butcher begins his hike through the rough country of western Bosnia does the brilliance of the book's underlying idea become clear. We begin to see the world through Princip's eyes. These were the hills he climbed and the paths he walked. The flinty scree that cuts into Butcher's hiking boots also moved under Princip's feet as he walked to Sarajevo. Princip was, like most Bosnian teenagers and like Butcher himself, an avid fisherman. The sparkling streams that make Butcher twitch with thoughts of trout must also have caught Princip's eye. The stony ground, the bitter nocturnal frosts, the hardscrabble life of the people who still eke out a living there: all this says much about the world that made Princip. Could it be, Butcher wonders, that the isolation and self-reliance of these mountain communities encouraged them to see neighbours as rivals for scarce resources, or even enemies, rather than as fellow citizens?