Author dials up the horror in new novel

Acclaimed horror writer Lauren Beukes takes a man with a dream and makes hima nightmare come true for all around him, writes Stuart Kelly

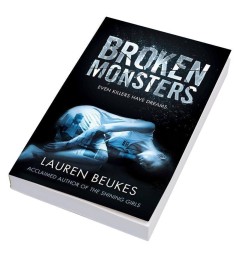

Broken Monsters

by Lauren Beukes

HarperCollins

4 stars

The distinction between genre and literary novels is increasingly a matter of marketing rather than critical inquiry. John Banville moonlights in crime as Benjamin Black, Jonathan Lethem uses aliens to explore humanity in Girl in Landscape, just as Nnedi Okorafor does in her sci-fi novel Lagoon. Percival Everett has given us a multicultural western in Wounded, Lucy Ellmann has turned the medical romance inside out with Doctors & Nurses and Helen Oyeyemi consistently reinvents the ghost story.

"Horror", though, still has a vaguely disreputable tang. There have been notable successes - Colson Whitehead's Zone One, Robert Shearman's Remember Why You Fear Me - but stereotypes of the video nasty in print still prevent it being taken or deployed seriously. And horror does indeed have issues. There's a certain laziness about gender questions that can easily slip into outright misogyny. There is the difference between being shocking and playing for shock value.

Since horror deals with primal fears ... [But] too often horror has confused the sublimely horrific with the simply horrible

Since horror deals with primal fears, it has to deal with fearful things: just as it is difficult to write a novel about pornography without being pornographic, or boredom without being boring, too often horror has confused the sublimely horrific with the simply horrible. If you're going to handle pitch, it's wise to wear sturdy gloves.

It is interesting, therefore, that much of the best contemporary horror is being written by women - Sarah Lotz, Kelly Link, Gemma Files and Sara Gran among them. Best known in the field, perhaps, is Lauren Beukes, whose previous novel The Shining Girls caught the attention of the mainstream.

That novel was, I think, underestimated at first. It is about how misogyny adapts to and exploits every freedom feminism achieves. Some reviewers were wrong-footed by a perceived lack of explanation about how the malign drifter Harper Curtis was connected to the supernatural House that allowed his time-travelling.

Yet as Harper literally bleeds into the House, we are shown that hatred of women is the architecture, the framework, the structure of this horror: the House is the default position of reality.