Book review: Winsor McCay: The Complete Little Nemo, by Alexander Braun

Place a pillow on this behemoth and it can serve as a bed for a small child - fitting given its subject matter is a once hugely popular comic strip about the dream life of a young boy.

by Alexander Braun

Taschen

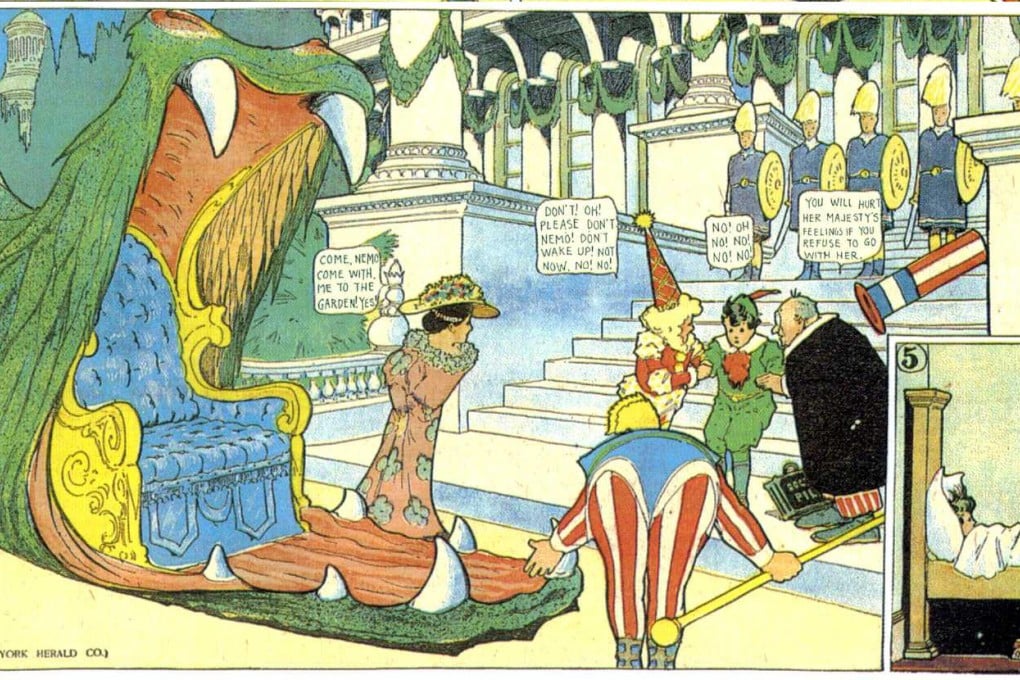

Winsor McCay's Little Nemo in Slumberland ran from 1905 to 1926, alternately appearing in the New York Herald and the New York American. All 549 episodes are here - in glorious colour and broadsheet size - in a gargantuan tome packed in its own carrying case.

Accompanying the hardback strips volume is a paperback book styled to resemble contemporary newspapers, a fascinating mélange of criticism, history and biography that attempts to put McCay in the cultural context art historian Alexander Braun feels he deserves.

The "funnies" were important drivers of newspaper circulation, providing cheap, easy-to-consume entertainment, especially for the working man who had only Sunday off and the immigrants with rudimentary English. Many creators have been forgotten, their work pulped, while others have recently been reassessed: McCay is one of the greats. Modern comics titans such as Neil Gaiman and Alan Moore have paid homage to McCay's most famous strip in their own work and it's immediately apparent why.

A natural talent - "I drew on fences, blackboards in school, old scraps of paper, slates, sides of barns - I just couldn't stop" - with a photographic memory, McCay's mastery of line, colour and perspective is incredible, and Nemo's world of dreams, where anything is possible, allows his imagination to take full flight.