Beaten, hit with an iron, doused in bleach: the Hong Kong domestic helpers facing systemic abuse and how city could protect them

In a new book, Hong Kong academic Hans Ladegaard tells 300 helpers’ stories of abuse and examines its patterns and causes. He tells of the steps that can be taken to safeguard them and deal with ‘evil’ employers

The angry outburst directed at Maryane, punctuated by blows from her female employer, was triggered by an innocuous mistake: the 28-year-old Indonesian helper had forgotten to put the butter on the breakfast table.

“What is missing? [slap],” her employer shouts. “I have reminded you many times. You have a poor memory … You better die [slap]. Why aren’t you dead? You better jump off the building and kill yourself. You make me so angry every day; you better die.”

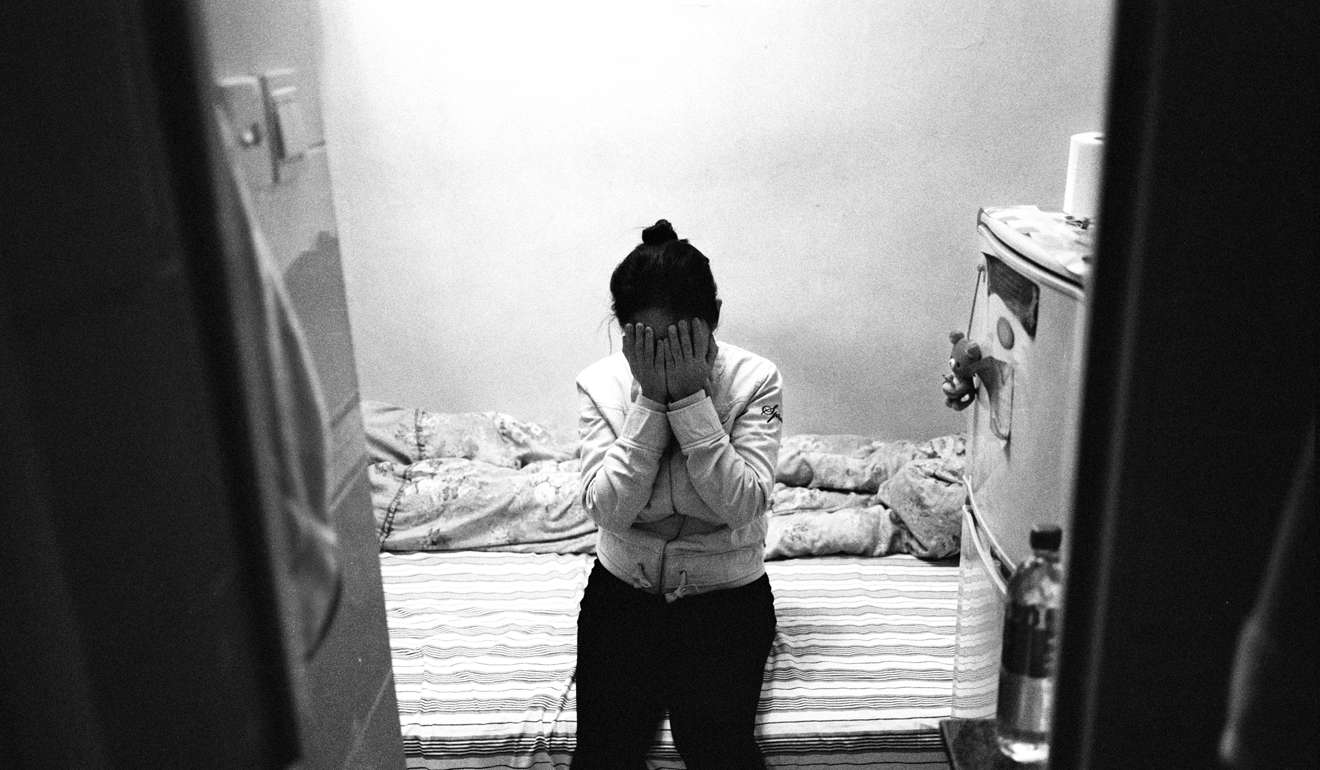

Maryane was beaten over a period of four months by her Hong Kong employer, who made her work 16 hours a day and sleep in the toilet. On occasions she was dragged across the floor by her hair. She used her mobile phone to record her beatings and to take pictures of her swollen face and bruises.

Eventually, with no money or belongings, she fled to a shelter for abused helpers run by the Mission for Migrant Workers. There, one day later, she told an interviewer: “She always beat me every day. She beat me like an animal.” However, after detailing the abuse and showing the evidence of her injuries, she insisted timidly: “I’m not angry with my employer; this is my mistake.”

Maryane’s story is one of more than 300 testimonies collected at the Bethune House shelter in Jordan by Hans Ladegaard, head of English at Hong Kong Polytechnic University, for an upcoming book that meticulously examines the patterns and causes of helper abuse in Hong Kong.

Rutchel, a 40-year-old Filipino, describes how she is forced by her employer to drink dirty water from a mop as punishment for rinsing it in the sink. “She got the mop, she got the glass and she said ‘You drink it you are very stupid, you are so dirty’,” Rutchel says. “I drank because she forced me.”

You have a poor memory … You better die (slap). Why aren’t you dead?

When her employer later threatens her and throws away food she’s bought for herself, Rutchel calls the police and meets them outside the building, telling them: “There’s a bad madam inside that house. That house is like hell.”

Esther, 32, another Filipino, was beaten with an iron for getting lost while taking her employer’s daughter to a pet shop five days after she arrived in Hong Kong. She suffered a broken cheekbone and went to hospital, where sympathetic nurses urged her to report the assault to police.

Ladegaard’s book – The Discourse of Powerlessness and Repression, being published by Routledge later this year – reaches uncomfortable conclusions about the issue of violence against helpers, which has been repeatedly dismissed by police, government officials and employer groups as rare or exaggerated.

The book paints a painful picture of systemic failings and prejudices that allow abuse, albeit not necessarily widespread, to continue unchecked, leaving vulnerable helpers in abusive homes with few means of escape or access to practical help.

Among Ladegaard’s starkest observations is that the “overwhelming majority of abusive employers” in Hong Kong are Chinese women, although he stresses they become abusive for social and psychological reasons, not gender or ethnicity.

She got the mop, she got the glass and she said ‘You drink it you are very stupid, you are so dirty’

He characterises the abusers as “lonely female employers who have no professional career, whose husbands work long hours and who have also lost the position they once enjoyed as head of the household”.

In that powder keg setting, a helper can be perceived as a threat, and seen as belittling or humiliating her female employer – as in the case of 27-year-old Indonesian helper Mona.

“My madam is always jealous of me because my sir is good to me,” says Mona, who was ordered by her female employer to stand in the kitchen for two nights without sleep. “Those two nights I was tortured by not being allowed to sleep. I was told to stay in standing position, and then in the morning she hit me, cut my hair and poured bleach on me.”

The abuse of helpers appears to be aided rather than checked by employment agencies run by their own nationals which, on paper at least, are meant to safeguard their interests. They take a large portion of their earnings in their first months in Hong Kong, often on the basis of non-existent training courses.

Indonesian helpers usually pay HK$3,000 a month for seven months to their agency – a total of HK$21,000 – while Filipinos pay HK$3,000 for five to seven months, Ladegaard says.

Most agencies offer a so-called BOGOF (buy one get one free) deal, which allows employers to try out one or more helper for three months, return her to the agency after that period, and get another one with no additional fees.

If Hong Kong wants to be Asia’s World City, there are certain types of behaviour we cannot and should not tolerate

Despite the huge sums the agencies charge helpers, however, Ladegaard notes: “In the 300-plus stories I have recorded in Hong Kong, I do not have one single example to show that a helper received any help from the agency to which she has paid almost her entire salary for half a year or more.”

Helper abuse is an “an inconvenient truth” that police, government and consular officials in Hong Kong appear to have no interest in tackling, Ladegaard argues, creating a system that effectively enables and even passively endorses it.

When a conference was organised at the City University of Hong Kong two years ago for consulates and government officials to discuss helper abuse with NGOs, government officials failed to show up and consular officials “did their best to downplay the seriousness of the issues”, Ladegaard writes.

Only when cases are highlighted in the media – such as the 2014 abuse of Erwiana Sulistyaningsih, whose employer was jailed for six years after Erwiana was found covered in burns and scars at Hong Kong International Airport – are officials willing to act, Ladegaard says.

A commonly accepted narrative is that helpers lie or exaggerate when describing abuse, he says. However, Ladegaard says of his research: “If domestic migrant worker narratives were generally untruthful, they would probably constitute the most shocking example of collective lying in human history.”

Asked what solutions he sees to the issue, Ladegaard tells the Post: “Employment agencies should be monitored much more closely by the Labour Department. Are the agencies doing their job in terms of representing their clients and protecting their rights? More often than not, they work for the employers, not the domestic workers who have paid extortionate fees to them.

“Employment agencies ought to monitor the employers to ensure that domestic workers have proper accommodation that complies with the law, that they don’t underpay their employees, that they get Sundays and public holidays off, and that they get enough to eat.

“At the moment, we have reasonable migrant labour laws in Hong Kong but no mechanism whatsoever to ensure that these laws are being enforced, and that’s a major problem. And like migrant worker NGOs have pointed out repeatedly, I would also suggest that the government reviews the live-in policy and the two-week rule.

“We know for a fact that many domestic workers stay with abusive employers because they know they will be deported after two weeks if they don’t have an employer – and who can find a new employer in two weeks? Violence against domestic workers would also decrease, I believe, if helpers were allowed to live out.”

Under current circumstances in Hong Kong, however, there are only a few glimmers of hope from the experiences of the abused women whose ordeals Ladegaard documents.

Esther, who suffered a broken cheekbone when she was struck with an iron, says she was urged by police not to pursue action against her employer, but she insisted on proceeding. She moved into a shelter, was supported by a pro bono lawyer from the Mission for Migrant Workers, and won compensation from her employer, who was forced to pay her full wages from the day of the assault to the day of the verdict.

Rutchel, who called police and told them the house was “like hell”, had the satisfaction of standing up for herself and fighting back, even though police took no action on her complaint.

We have reasonable migrant labour laws in Hong Kong but no mechanism whatsoever to ensure that these laws are being enforced

Maryane, on the other hand, who had the recordings and photographic evidence of her abuse and arguably the most compelling legal case against her employer, refused offers to take her employer to court. Instead, she went back to Indonesia, vowing never to return to Hong Kong.

Ashamed, humiliated and still blaming herself for her ordeal, Maryane says: “I don’t want to let my parents know what happened.”

Maryane’s case in particular, Ladegaard argues, raises important moral and philosophical issues. “If Hong Kong wants to be Asia’s World City, there are certain types of behaviour we cannot and should not tolerate.

“Maryane’s story represents a limit case in our thinking on ethics. It somehow exceeds what we might call the unethical and might be better captured under the category of evil.

“Although modern philosophy and anthropology have virtually abandoned evil as an analytical concept, and consigned it to theology, it seems appropriate to reintroduce it to characterise intentionally demeaning behaviour that appears to serve no other purpose but to humiliate and dehumanise another human being.”