Internal contradiction

The law that limits fertility treatment to heterosexual married couples is outdated and should be changed, experts tell Elaine Yau

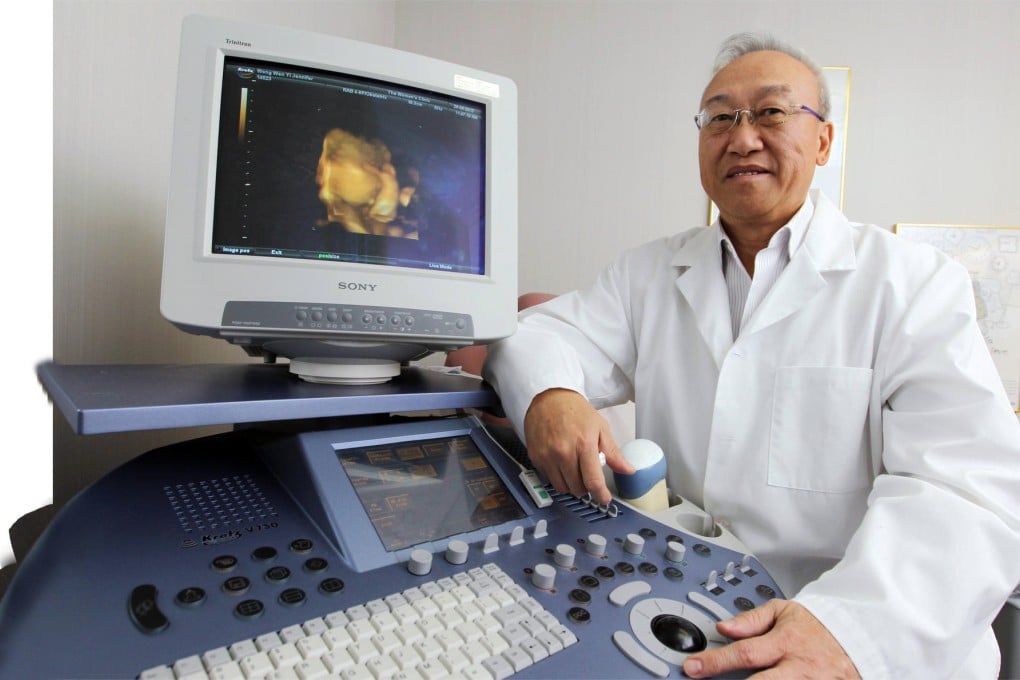

Since Dr Milton Leong Ka-hong delivered Hong Kong's first test tube baby in 1986, help with procreation has been transformed. Back then, drugs to help women with ovulation were far less effective, sperm banks and donor programmes were the main ways to tackle male infertility, and success was hit and miss.

Now, conception is possible if specialists are able to extract just one viable sperm and egg. Still, fertility treatment remains a fraught process, with frequent injections and consultations with obstetrics and gynaecology specialists such as Leong.

For 41-year-old finance manager Rebecca (not her real name), the quest to conceive was filled with even more obstacles. The Briton didn't plan to marry, and as a single woman, she was not allowed to receive artificial insemination in Hong Kong. So she had to look abroad.

"I got sperm from a donor in the US, which was flown to a Thai clinic that could get everything done. I found a gynaecologist here who agreed to do the monitoring, and I would take the drugs and undergo the actual procedures in Thailand. For the four cycles of intrauterine insemination, I had to fly in and out of Thailand all the time. It was very expensive. But it didn't work," she says.

"Luckily, I found a doctor here who was prepared to be a bit more flexible. He wouldn't do any surgical work, but he prescribed the drugs which I self-administered at home to encourage ovulation. It's very lucky I found this guy, because it's a grey area. The others were unhelpful. It took nine days for the drugs to take effect and I flew to Thailand for retrieval and transfer of embryos."

She became pregnant last year after two attempts at in-vitro fertilisation, and gave birth to a baby boy. But Rebecca says her bid to have a child was far more difficult than it needed to be. "It's difficult to keep a regular job and spend so much time away," she says.