Internal contradiction

The law that limits fertility treatment to heterosexual married couples is outdated and should be changed, experts tell Elaine Yau

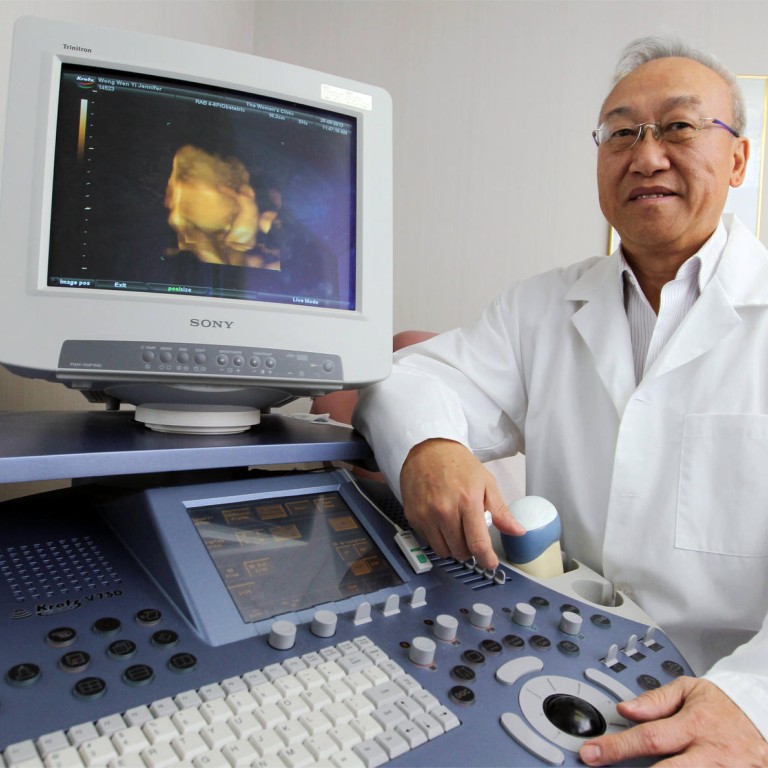

Since Dr Milton Leong Ka-hong delivered Hong Kong's first test tube baby in 1986, help with procreation has been transformed. Back then, drugs to help women with ovulation were far less effective, sperm banks and donor programmes were the main ways to tackle male infertility, and success was hit and miss.

Now, conception is possible if specialists are able to extract just one viable sperm and egg. Still, fertility treatment remains a fraught process, with frequent injections and consultations with obstetrics and gynaecology specialists such as Leong.

For 41-year-old finance manager Rebecca (not her real name), the quest to conceive was filled with even more obstacles. The Briton didn't plan to marry, and as a single woman, she was not allowed to receive artificial insemination in Hong Kong. So she had to look abroad.

"I got sperm from a donor in the US, which was flown to a Thai clinic that could get everything done. I found a gynaecologist here who agreed to do the monitoring, and I would take the drugs and undergo the actual procedures in Thailand. For the four cycles of intrauterine insemination, I had to fly in and out of Thailand all the time. It was very expensive. But it didn't work," she says.

"Luckily, I found a doctor here who was prepared to be a bit more flexible. He wouldn't do any surgical work, but he prescribed the drugs which I self-administered at home to encourage ovulation. It's very lucky I found this guy, because it's a grey area. The others were unhelpful. It took nine days for the drugs to take effect and I flew to Thailand for retrieval and transfer of embryos."

She became pregnant last year after two attempts at in-vitro fertilisation, and gave birth to a baby boy. But Rebecca says her bid to have a child was far more difficult than it needed to be. "It's difficult to keep a regular job and spend so much time away," she says.

Many of the hurdles lie with obsolete restrictions under the Human Reproductive Technology Ordinance which, among other things, dictates that fertility treatment in Hong Kong can only be offered to heterosexual married couples.

"I understand you need to be careful about the use of human tissue. But basing the decision solely on marital status is completely old-fashioned. I can't even have a consultation with a doctor here without showing a marriage certificate. I am a single parent by choice," Rebecca says.

"It's like [the government] has made a moral judgment that all people who are not in a heterosexual marriage, like single women, lesbians and cohabitating couples are not fit to be parents."

Many professionals in reproductive medicine, as well as rights groups, share that view. Yeo Wai-wai, a spokeswoman for gender rights group, the Women Coalition, says its restrictions are so broadly defined that unmarried people who seek fertility treatment abroad would also be breaking the law.

"We've also had inquiries from lesbian couples who are locals, but sought treatment overseas. They are scared that they have broken the law. There are many unmarried people of different nationalities living here who get procedures done overseas, where it is a normal practice. If they were Hong Kong citizens, they would have broken the law."

Many problems arise because the ordinance is outdated, says Leong, a former president of the Hong Kong Society for Reproductive Medicine. It was drafted in the 1980s, when a primary concern was to prevent the possibility of incest. At the time, donor insemination had just been introduced in Hong Kong and the Family Planning Association was setting up a sperm bank. So the government was keen to ensure that two people fathered by the same sperm donor would not end up marrying each other. That's why the law specifies that a sperm or egg from a single donor can only used to conceive up to three babies.

But when the ordinance was finally passed in 1997, medicine had advanced considerably. And by the time the Council of Reproductive Technology was established to police the provision of reproductive procedures in 2001, technological advances had made the use of donated sperm largely unnecessary.

Donor insemination was more prevalent - and important - during the 1980s and 1990s, Leong says. But the emergence of newer techniques - using micro-needles to insert a sperm directly into the egg, for instance - meant physicians did not need a lot of sperm from the father to fertilise an egg.

Leong says there was considerable misunderstanding among the drafters when the ordinance was being drawn up.

"When they were discussing the law, the first IVF baby was born [in Hong Kong], in 1986. Many didn't know what a test tube baby was; they thought it meant babies involving donated sperm. But that's just one kind of [artificial insemination].

"Of about 7,000 cases of assisted reproduction conducted annually, less than 1 per cent involve donation. Why do we need this outdated ordinance, and all that administrative work to monitor those few?" Leong asks.

Council figures seem to bear out the argument. There were 4,693 fertility treatments conducted in Hong Kong in 2009 (donor insemination, artificial insemination by husbands and other procedures). Yet just one of them involved donated sperm. Similarly, just three of 7,749 treatments the following year used donor sperm.

The council's key roles are to investigate issues of reproductive medicine like surrogacy and development of embryos, and to license infertility treatment providers.

So far it has issued 50 licences to clinics, hospitals and other medical facilities help married couples have babies, 36 of which are allowed to conduct artificial insemination using the husband's sperm.

But Leong, who runs an infertility treatment centre, argues the council should be more rigorous in its requirement of fertility service providers. Although the Code of Practice on Reproductive Technology and Embryo Research sets minimum requirements for centres offering in vitro fertilisation, it does not stipulate the training an embryologist should have, he says.

In contrast, Leong reckons the ordinance is overly stringent in requiring couples to register their ID and other personal details with the council each time they receive treatment, especially since some fertility courses last for years.

"A couple may seek infertility treatment for a variety of reasons, like a blocked fallopian tube or insufficient sperm. But [the solutions] do not involve a third party like donor insemination. There's no need to create unnecessary troubles for them," Leong says.

Council founding member Edward Loong Ping-leung says the requirement essentially prevents the use of donor sperm, which used to be bought from sperm banks overseas. "Sperm donors do not intend to disclose their identity beyond the centre where the donation is made. The requirement almost eliminates the availability of sperm donors from abroad."

A council spokesman said it is required under the ordinance to maintain the register, which covers all information relating the provision of a reproductive technology procedure. The aim, he says, "is for the recipients [of the procedure] to be able to verify if there is any inadvertent incest".

"No person shall provide a reproductive technology procedure to persons who are not the parties to a marriage," the spokesman says.

That stance may have to change before long. The concept of family has changed a lot in the past 20 years, says Tik Chi-yuen, chairman of parents group the Hong Kong Institute of Family Education. "We see more and more people having babies without getting married. While I don't necessarily support homosexuality, there are more family units consisting of single parents and cohabitating couples," Tik says.

"The concept of having a child after marriage is outdated. Social mores have loosened and we have embraced all kinds of family arrangements like single career women raising children on their own." It's time the government reviewed the law so that people who want to fertility treatment can have a choice, he says.

Winnie Chow Weng-yee, a family law specialist and partner in Hampton, Winter and Glynn, concurs. "Reproductive technology, the medical side of it, is advancing in leaps and bounds. But the law has been completely stagnant," she says. The research and consultation exercises that led to the ordinance were done in the 1980s and 1990s.

"We are now in 2013. We are looking at least at a 20- to 25-year gap. It's a whole new generation. What is in the ordinance is not necessarily in line with social norms."

Clients have asked her about options in Hong Kong, and many are disappointed when they realise other jurisdictions are much more accommodating. The ordinance has not been tested in court, so there is no guidance on how it would be interpreted, Chow says.

"But I think it's a narrow-minded view that a married heterosexual couple constitutes the ideal setting to raise children. Just because somebody is married doesn't necessarily make him the best parent," Chow says. "The law in Hong Kong is guided by the principle of what is in the child's best interest. It's in a child's best interest to have a loving and caring parent. It should be based on the individuals, on whether they can care for the child. Not on their marriage status."

Banned in Hong Kong

The Human Reproductive Technology Ordinance forbids:

- fertility treatment for unmarried people

- sale of sperm or egg

- surrogacy arrangements involving payment in Hong Kong and elsewhere

- gender selection of the baby for non-medical reasons