Rebels on the red carpet as actresses’ clothing becomes a hot political topic – again

Trousers and men’s tailored suits are turning up on the red carpet again, recalling the first time such apparel made an appearance there – the 1960s and ’70s, not coincidentally also a period of protest and turmoil

Red carpet fashion is not fashion as we know it. It does not adhere to seasonal trends, nor attempt to make arch statements. Shifts in silhouette occur at a glacial pace. Since the 1930s the dominant look has either been that of a Disney princess – skirt puffed out with tulle to emphasise a tiny waist – or something long, slinky and draped. The only true recent development has been the rise of cut-outs on dresses, putting on show sections of the body that were previously hidden by corsetry and thus necessitating new descriptors, such as the side boob and the prime rib.

But while the headline trends of awards season so far have been pretty typical – sequins, tulle and daffodil yellow – there is something else happening among a handful of women that feels remarkable. Women are wearing suits. Not fluid pyjama-style co-ordinates that slip off the shoulder, but boxy, Fred Astaire-style tailoring.

At Sunday night’s Screen Actors Guild awards, Evan Rachel Wood wore a midnight blue velvet Altuzarra, continuing a promotional run in which she has declared that she will only wear suits. At the Golden Globes, she wore a black tuxedo over a frothy white Purple Rain blouse, her hair an androgynous quiff. “I love dresses. I’m not trying to protest dresses,” she said. “But I want to make sure that young girls and women know they aren’t a requirement and that you don’t have to wear one if you don’t want to.”

The Oscars: who ruled the red carpet and who failed to impress

The more you think about it, the weirder it is that a woman wearing trousers can still be interpreted as an overtly political act. It says something about the world that the most dated of fashion rules – trousers for men, skirts for women – is so rarely broken at awards ceremonies, the most high-profile and influential of fashion events.

The first time women wore suits on the red carpet was in another period of protest and change: the late 1960s and 1970s, when the Hollywood studio system was dissolving. In her book about the history of the Academy Awards and fashion, Made for Each Other, Bronwyn Cosgrave explains that actresses were suddenly attending awards ceremonies on their own terms, and not on the arm of patriarchal studio bosses. They wore dresses that they had chosen themselves, rather than outfits paid for – and decreed by – the studios. The way in which they dressed more accurately mirrored fashions of the time – Yves Saint Laurent’s groundbreaking trouser suits were designed in 1966 – and women’s changing roles and lives.

Still, the results were not always successful. In 1969, Barbra Streisand was the first best actress winner to wear trousers, but her shimmering jumpsuit caused an international furore when its fabric turned see-through under the spotlights and showed the world her bottom. That outfit, according to Cosgrave, was the beginning of “a two-decade phase through which individuality and self-expression ruled the Academy Awards”, when actresses realised they could use red-carpet fashion to generate worldwide headlines. In other words, without Streisand’s buttock-flashing outfit there would have been no Cher in her feathered headdress and no Björk dressed as a swan laying an egg.

For Jane Fonda, in 1972, wearing trousers represented feminism and activism. She wore a black Yves Saint Laurent suit with a Mao collar during a period in which she was determinedly not “dressing for men” – in a reaction to the skimpy catsuits and thigh-high silver boots she had famously worn as Barbarella (her brown shag haircut was the opposite of Barbarella’s Bardot-esque bouffant). The suit served as a visual reminder of her campaigns against the Nixon administration – she had previously sent a Vietnam vet to the podium to collect her Golden Globe – although on Oscars’ night, with boos emanating from the audience, she did not actually deliver a protest speech.

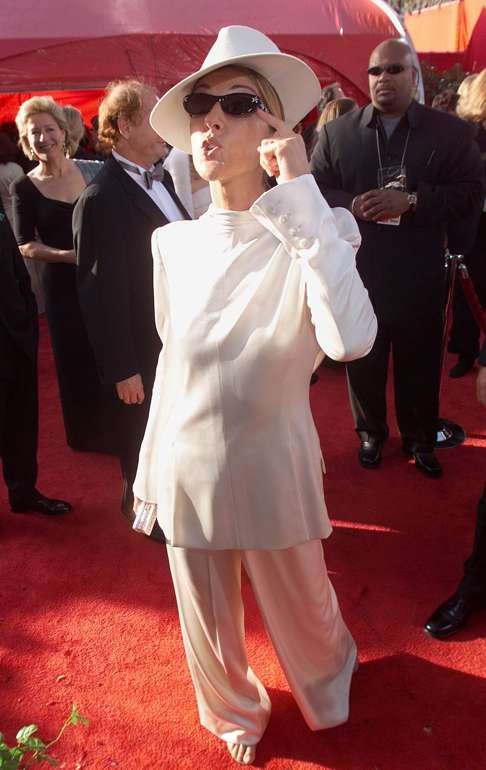

There have been others. Diana Ross wore a satin Bob Mackie suit in 1973; Faye Dunaway wore loose trousers in 1977; Sissy Spacek wore a sleek black jumpsuit in 1981. Jodie Foster collected her Oscar in putty-coloured Armani in 1992, while Julia Roberts wore a men’s Armani suit at the Golden Globes in 1990. Céline Dion’s take on tailoring was one of the most eccentric Oscars outfits of all time – a white suit worn backwards in 1999, while Brangelina had a his-and-hers tuxedo moment in happier times. But women in suits has never caught on as a wider trend. In fact, moments of red carpet individualism, skirted or otherwise – think of Lauren Hutton in a spangly gold minidress in 1980 or Kim Basinger in her home-made Frankenfrock in 1999 – have been in very short supply.

Hillary Clinton’s other legacy: pantsuits for winter

This has been bad news for all human women, because the red carpet is one of the most high-profile examples we have of women, en masse, being celebrated for being at the top of their game.

Two years ago, the well-meaning Ask Her More campaign urged interviewers not to ask actresses about the clothes they were wearing, an endeavour that proved tricky in the face of so many lucrative endorsement deals.

This awards season, something different is happening: women are not ignoring fashion but using it to make a genuine statement. As well as the women in political pantsuits, there have been others wearing creations that could be described as idiosyncratic – Ruth Negga in weird, robotic sequins; Nicole Kidman in a peacock Gucci cheese dream of a dress; Bryce Dallas Howard wearing high-street fashion. And there have been explicit messages of protest. At the Globes, Transparent creator Jill Soloway and actress Lola Kirke used their outfits to explicitly protest against the Trump administration, wearing badges that said “F*** Paul Ryan”, of which Kirke commented: “As a person with a platform, no matter what size it is, I think it’s important to share your views and maybe elevate people that might agree with you, that maybe won’t feel like they can have the same voice.”

With the Baftas and the Oscars around the corner, one can only hope that this trend has legs.