The tradition of New Year food hawkers, and why Hongkongers are so attached to them

For years food stalls were the only place to buy cooked food over the holiday, and generations grew up eating food such as fishballs from them, making street hawkers a cherished part of local culture

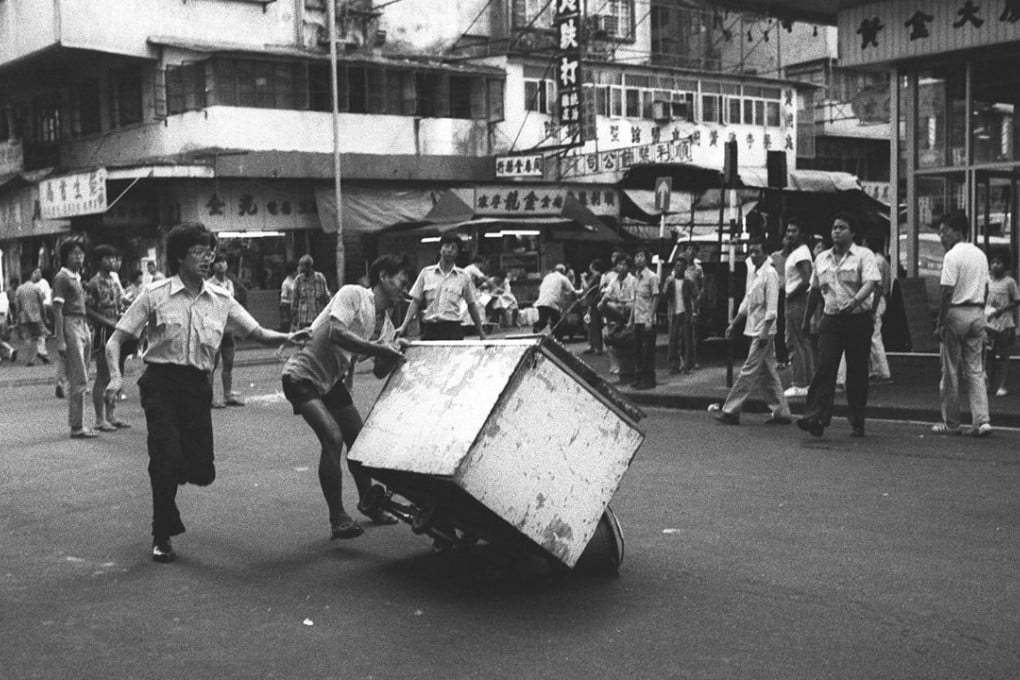

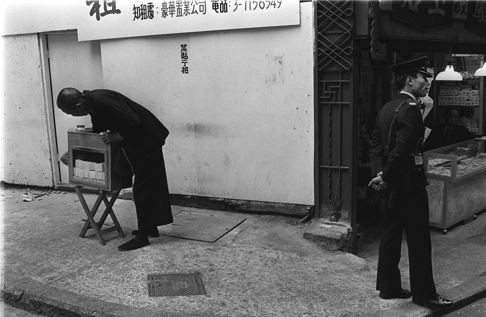

The spark for Monday night’s rioting in Mong Kok and a subsequent incident in Tuen Mun was government enforcement action against hawkers selling street food - a Chinese New Year tradition going back decades. We asked food writers about the history of the practice, Hongkongers’ attachment to street food and what they think will happen now.

Food and travel writer Chan Chun-wai, 45, fondly remembers eating food from hawkers who set up shop during the first three days of Chinese New Year.

“At home there wouldn’t be much to eat except for those auspicious, expensive dishes like braised oysters, steamed fish and whole chicken,” Chan says. “So it was only around this time of year that my parents would let us kids out to eat street food. The hawkers would set up in an open area and bring out tables and stools. We’d get things like offal, braised fish balls with pig skin, and cart noodles and dine al fresco. This only happened for three days because restaurants would reopen on the fourth day.”

“Living in public housing estates we didn’t have much exposure to other cuisines, so for me it was my first time trying them. There were also many pancake stalls, and traditional candy and coconut wrap, where a honeycomb-shaped white wafer was dressed with sugar, shredded coconut, maltose and sesame and wrapped in a thin pancake,” he says.