Hong Kong food pairings for sake: pasta, hotpot, barbecued meat – yes, Japanese spirit is bursting out of its confines at last

While wine is drunk with most foods in Hong Kong, sake was confined to Japanese restaurants until innovators such as Balinese restaurant Potato Head began matching it with other cuisines

In an era of barrel-aged artisanal beers and handcrafted micro-batch spirits, there’s a distinctive blur between beverage categories, even before taking a sip.

Enter sake. Is it “wine” or a “spirit”? Perhaps it is closer to beer? In a label-loving metropolis such as ours, identity is important.

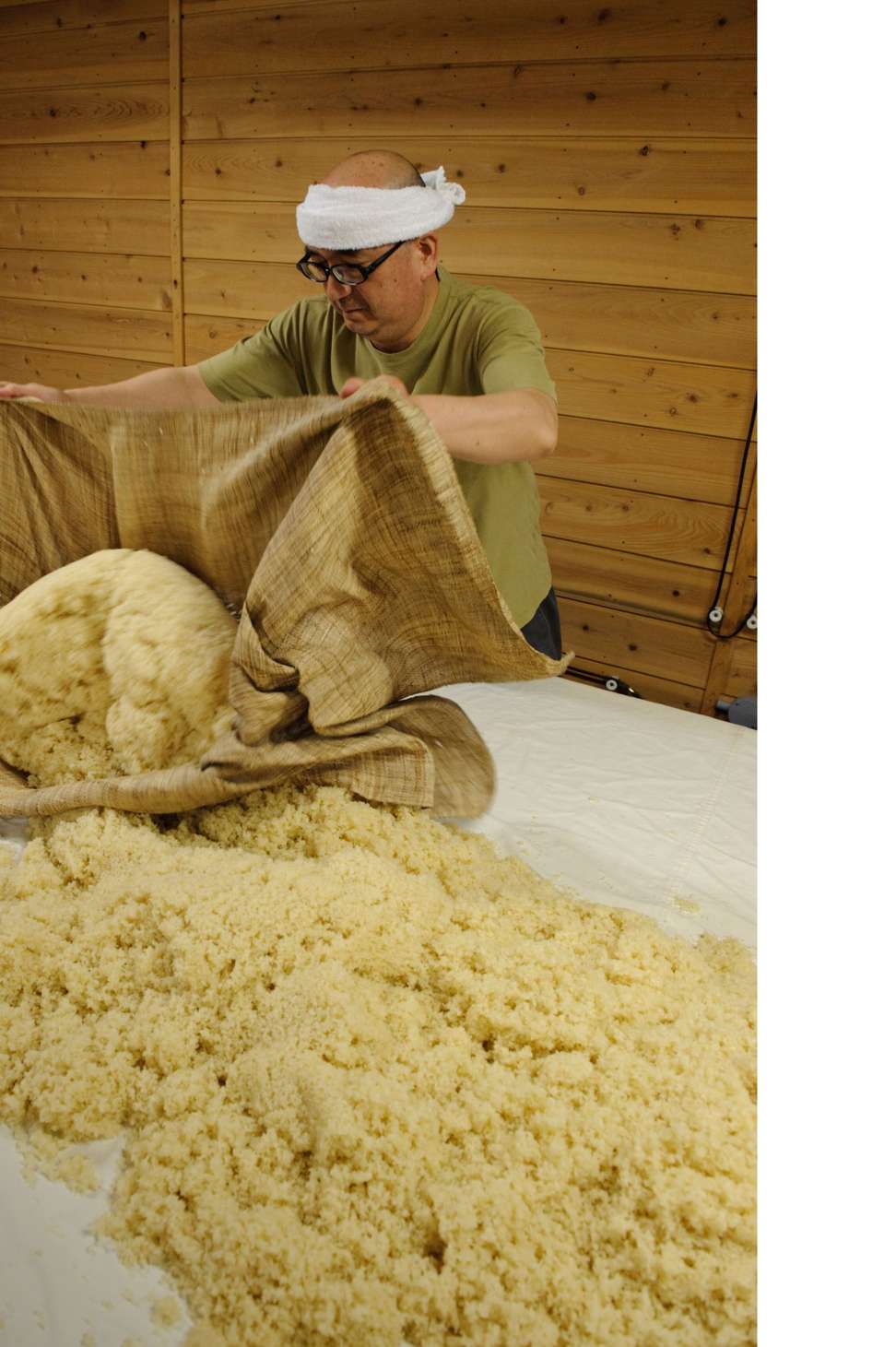

With “rice wine” an ever-popular nickname, many see sake as closest to its grape wine counterpart. Like wine, most sake breweries are “artisanal”, producing a handcrafted product using natural materials. Rice, yeast and mould form the basis of sake, which is akin to the main natural ingredients which constitute grape wine – grapes and yeast.

The traditional business model of sake also echoes winemaking, with many producers being family businesses. This multigenerational workforce ensures the longevity of traditions and a vested interest in long-term success. We see this repeatedly in wineries, particularly in Italy.

But there are plenty of differences between sake and wine. The source and sourcing of ingredients differ vastly. The majority of sake producers do not grow their own rice, with most purchasing the grain directly from a rice miller. Only a tiny minority have their own mini mills.

However, for many winemakers, viticulture (grape growing) is integral to the winemaking process. Planting, harvest, and the meticulous cultivation of vines is not only a labour of love; many feel that controlling this aspect of winemaking is fundamental to the winemaking process and the eventual end product. Why the hands-off approach for sake producers? Unlike the oft-fickle grape, rice is a hearty grain which exhibits very little seasonal variation.

Age matters, too. Grape wine is usually made to improve with age. Sake is almost always made for immediate consumption, with a “fresh is best” motto. Although aged sake exists, it’s a niche market.

Unlike wine, sake boasts a relatively simple classification system, which makes identifying your favourite style quite simple. That said, tastes and flavours range from fruity, floral, smoky, and earth, to slate or stony … hello vino!

Long the hometown hero of the Japanese market, is sake a sensation in Hong Kong? Ask a samurai.

Beverage director of Yardbird, Ronin and Sunday’s Grocery Elliot Faber was awarded the title of “Sake Samurai” last year – an honour bestowed on just a few dedicated professionals annually, and fewer than 40 non-Japanese people in its 17-year history.

Faber says: “Sake Bar Ginn [in Lan Kwai Fong] is still the gold standard for sake education and enjoyment. Owner Ayuchi Momose continues to celebrate the sake seasons and always has a unique offering.”

With more than 100 premium sakes, it’s certainly a great place to start.

Beautiful packaging makes sake attractive to Hong Kong’s bling-loving tipplers, and our familiarity with Kanji labels is also a plus. Also, the proliferation of Japanese restaurants means sake is readily available throughout Hong Kong.

Yet unlike wine, which has successfully integrated with most international cuisines, sake seems confined to accompanying Japanese food. This is surprising, as its delicate flavours are well suited to seafood, a big tick when it comes to Cantonese cuisine.

On what foods to pair sake with, Faber advises: “Don’t be afraid to have it with barbecued meat, or pasta, or hot pot, or whatever you happen to be having that evening. If wine can go with Japanese food, sake can go with international cuisine.”

Kamil Foltan, group bars development manager for Potato Head, says: “We originally started the event – Kissaten 001 – with Japanese whiskies. But we chose sake for the last Kissaten because of its versatility as an alcoholic beverage. It complements any style of cuisine and brings a certain kind of joy to the music event.” Faber attests it “pairs stunningly with their Indonesian menu”.

So while not exactly wine, sake certainly stands side-by-side with its grape-based mate. Could its ambiguous identity be a factor in its slower rise to mainstream prominence? Or is this just the Japanese way – discreet, yet continually toiling to achieve long-term success, without the need for lucky breaks?

Debra Meiburg is a Hong Kong-based Master of Wine