The rural Indian inventor whose machine to make sanitary pads shattered a taboo and inspired a film, Pad Man

Feature film Pad Man tells the story of Arunachalam Muruganantham, who, shocked by his own wife’s secret suffering over menstruation, set out, against the odds, to invent a cheap sanitary pad maker now in wide use all over India

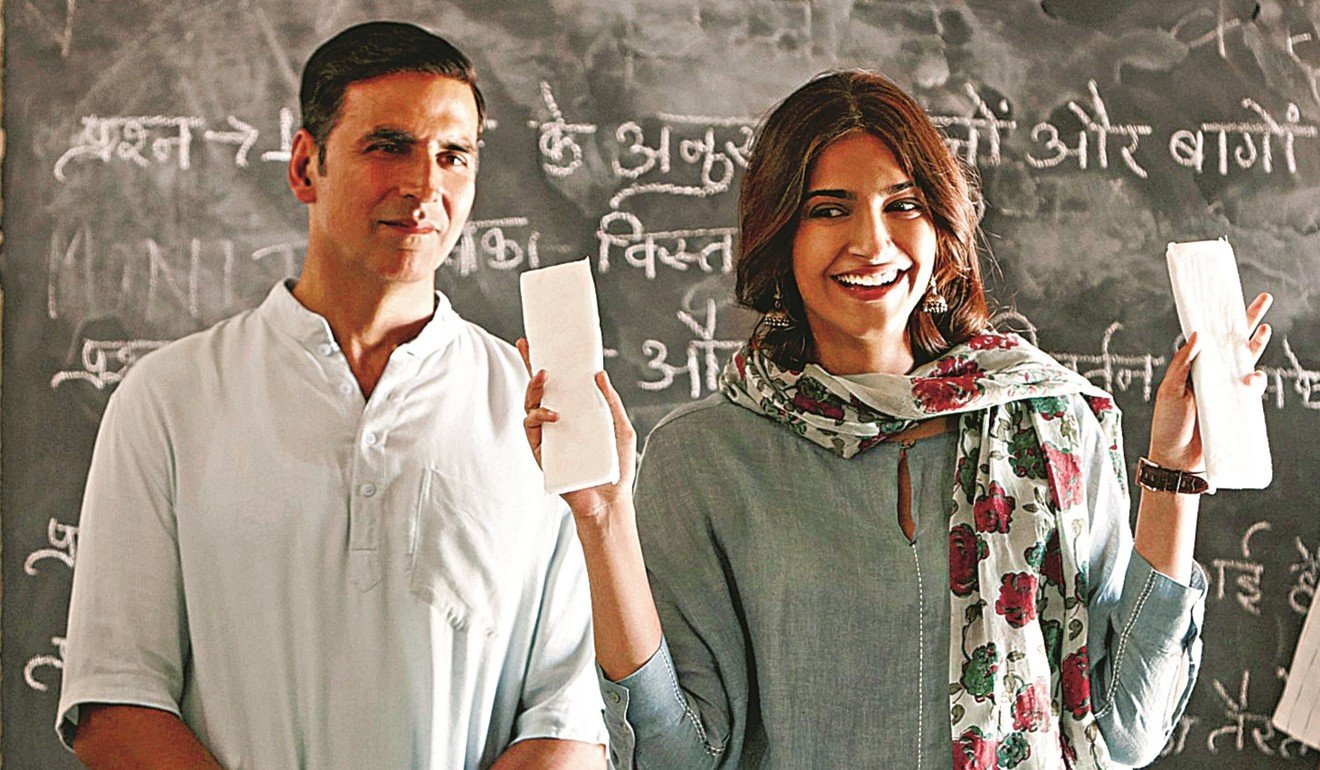

There is a scene in the film Pad Man in which Bollywood star Akshay Kumar’s character discovers his wife hanging up a dirty old rag to dry. She conceals it under the sari which is already hanging on the line.

It is something she uses, washes, and reuses. When he realises that it is the cloth she uses for her periods, he asks: “How can you use that? I wouldn’t even use that to clean my scooter.”

The film, released on February 9, is about the real-life mission of an ordinary villager, Arunachalam Muruganantham (played by Kumar), to help poor Indian women by inventing a revolutionary machine to make cheap sanitary pads.

Pakistani team develops menstrual game app to break taboos

It is a bold film for a highly conservative country where even talk of sex is taboo – so taboo that most Indians use the English word “sex” as there is no easy word in Hindi. Menstruation is a sordid secret, never to be discussed, even within a family.

After this encounter with his wife, Muruganantham becomes determined to end this nonsense over menstruation.

His life story is made for the screen. A man who is mad enough to think he can change the world and ignore the scorn of those around him – including the dismay of his own wife. She is so horrified at his messing around in public with wads of cotton wool and goat’s blood (he has to check the absorbency of his pad, poor man, otherwise what’s the point?) that she leaves him in horror.

If this story doesn’t provide the dramatic tension vital for a film, what does?

It is even a love story. Muruganantham, a social activist in a village near Coimbatore in Tamil Nadu, threw himself into his crusade out of love for his wife, Shanti, because he adores her and wants to safeguard her health.

When Muruganantham urges Shanti to buy sanitary pads, she says the family budget won’t stretch that far. As a gift, he buys her a packet from the chemist. As happens all over India, the shop assistant surreptitiously passes the packet, wrapped in black plastic, to him under the counter.

“Why are you behaving as though you are selling me hash?” he asks.

It should be as normal as the fact that we have to brush our teeth and have a bath. A sanitary pad is not a luxury item

This furtive exchange – and the research he did among the women in his village – makes him think. The more he learns, the more his incredulity grows. Rural women use strips of old newspapers, rags, leaves, or sawdust. Only 12 per cent of Indian women have access to sanitary products.

Even if there is a nearby chemist, the women mostly can’t afford sanitary towels. More often than not, though, there is no shop anywhere near.

Doctors say the use of rags or sawdust puts women at risk of infections, but they have no choice.

That is when Muruganantham starts trying to invent a cheap pad. His traditional wife, mother and two sisters are horrified, so orthodox that they are revolted by a man openly discussing a “woman’s issue”. He presses on, insisting he is doing it for their sake. They are humiliated by his attempts to find women in the village to test his pad because they refuse to do so (although Shanti does make a grudging attempt).

Since he won’t give up, his village ostracise him. His wife and mother leave him in disgust at his “perversion”. Worse, his pads are useless. Nothing works.

It took a long time for him to invent a machine that made proper pads, but his efforts won out in the end. His life took a turn for the better only in 2009 when he won an award from India’s National Innovation Foundation to make machines to manufacture sanitary pads in rural communities.

Local women operate the machines, which make biodegradable pads that cost just two rupees (three US cents) each. More than 600 machines have already been distributed in 23 out of India’s 29 states. Women earn income from making and selling the pads.

Nepali teen dies from snakebite after being banished from house for having her period

The film’s director, R. Balakrishnan – known as R. Balki – came on board to direct it after Twinkle Khanna, a social commentator (who is married to Akshay Kumar), approached him, saying she wanted to “normalise a normal biological function” in the film.

She told Indian media: “It should be as normal as the fact that we have to brush our teeth and have a bath. A sanitary pad is not a luxury item, it is a necessity.”

Balakrishnan is clear about the impact he wants his film to have. “I want Indians to watch it together as families and then be able to talk about periods, men and women, without discomfort or embarrassment, as something totally normal,” he said.

The wider issue that Pad Man highlights is the stigma that surrounds menstruation. In India, even educated women avoid the kitchen while on their period for fear of contaminating food, and wash their clothes separately. Entering a temple at that “time of the month” is prohibited.

Some rural women believe that if they venture out after sunset while menstruating, they will go blind. In India’s northeast, the practice continues of women being confined to a hut – notwithstanding cold, heat or deadly insects and snakes – as far as possible from the house.

While researching these taboos for her website, Menstrupedia, which aims to break the silence so that young girls feel more relaxed about their bodies, Aditi Gupta was horrified to find the lengths to which girls go to hide their periods from their families, out of shame.

“I came across a village girl who managed to hide her periods from her parents for a whole year – a whole year,” said Gupta.

Balakrishnan, like most Indian men, had never heard periods being openly discussed when he was growing up in Bangalore. But he used to sense things.

“My mother would sit in the courtyard during her periods. She didn’t go into the kitchen, either. Whenever someone else was preparing my meals, I knew,” he said.

Indian women join #HappyToBleed campaign to protest temple’s remarks on menstruation

Before the silence shrouding menstruation descends, there is the apocalyptic shock of the first period. Indian parents rarely tell daughters what to expect.

“I used to watch Bollywood films where, if someone was dying of cancer, they invariably coughed up blood. When I had my first period, I thought I was dying of cancer,” said Purnima Govindarajulu, a conservation biologist who grew up in Chennai.

China has similar taboos. When preparing paper dragons for Chinese New Year, it is taboo for menstruating women to be near the dragons when the cloth is being pasted to the dragon’s body.

In an article, “Menstrual Taboos – Anthropology of Gender”, academic Renee Pinkston wrote: “The Chinese also believe that during her menstrual period, a women is very unbalanced … women are not to wash their clothes and their husband’s clothes together; they are not allowed to sit on a chair that a man will occupy; are not allowed to worship gods in public ceremonies, public temples or even ancestral halls.”

At the 2016 Olympics in Rio de Janeiro, the Chinese swimmer Fu Yuanhui stunned the media by remarking that she was having her period. Many Chinese sports fans did not know a woman could swim during her period.

I need a boyfriend but can’t find the right match, says China’s Olympic sweetheart Fu Yuanhui

In the West, too, women are embarrassed by menstruation. A survey by Plan International, a development and humanitarian organisation that advances children’s rights and equality for girls, last year found that 58 per cent of American women felt embarrassed and 73 per cent hid pads and tampons from view.

In the UK, 26 per cent of girls did not know what to do when they first started their period, and 48 per cent said they felt embarrassed.

Muruganantham’s pre-release campaign on social media was critical to his mission. Called #PadManChallenge, he asked Bollywood celebrities – who responded sportingly – to share photos of themselves holding a pad.

“I wanted to drag those pads out of dark drawers into the daylight where everyone can see them,” he said.

During filming, when local actors were asked to hold a pad, most ran away.

“We have to break these taboos. When a man holds a pad in his hands and says he is not ashamed of it, that is where the mindset will change,” Kumar told The Times of India.

I want Indians to watch it together as families and then be able to talk about periods

For Kumar, the film is a bold choice. He seems to be at a stage in his career when he wants to use his stardom to shake up society and destroy some awful old traditions.

His previous film was Toilet: A Love Story, which urged Indians to stop open defecation and build toilets in their homes. It did surprisingly well at the box office because it combined a powerful story with a social message – without sermonising.

Nor is he totally critical of Indian men, saying that mothers and sisters keep periods a secret from the men in the house. “Men didn’t realise that periods are something they need to know about and understand,” he said in the same interview.

Balakrishnan believes that sometimes it takes just one impulse to get change started.

“Often you just need a stimulus to open up about a topic you were uncomfortable with. In a group, if someone brings it up, it gives you the licence to talk about it, too. That is what a film does, it provides a licence to break a taboo,” he said.

The film comes at a time when attitudes are beginning to change. Last year, two Indian firms in Mumbai introduced a policy to give female employees a “period day” off every month. The aim? Fighting the cultural sensibilities that surround periods in silence.

Last month, an MP introduced a private members’ bill, the Menstruation Benefit Bill, 2017 proposing that working women get two days of paid menstrual leave each month.

As for Muruganantham, the story ends happily. His wife returned to him nine years ago and is now proud of him. He is famous.

“I am pleased the film will help create awareness,” he says. What kept him going?

‘Having the painters in’: Women use 5,000 euphemisms for their period, survey finds

“My nature is such that even if I failed 9,999 times, I’ll attempt for the 10,000th time again. I always say ‘be near science and technology and you will never fail’. Because even if I fail today, I have faith that if I change the angle of a blade or a material tomorrow, the machine may work perfectly. And this way, I kept going on and never bothered about who was with me or not.”