Infertility: the woes couples on IVF face, and why there’s always hope

Receiving fertility treatment is often a stressful experience, but there are steps that can be taken to assist couples. One mother opens up about her experience in Hong Kong and Australia, and why she is trying for a second child nevertheless

Wilma Janner’s four-and-a-half years of assisted conception culminated in the successful birth of her son in 2016, but the whole experience was a harrowing one for the now 38-year-old.

Janner (not her real name) and her husband had been trying to conceive naturally but failed. “There was nothing medically wrong with us,” she says of the results of a sperm test, and ovulation tracking exams and scans.

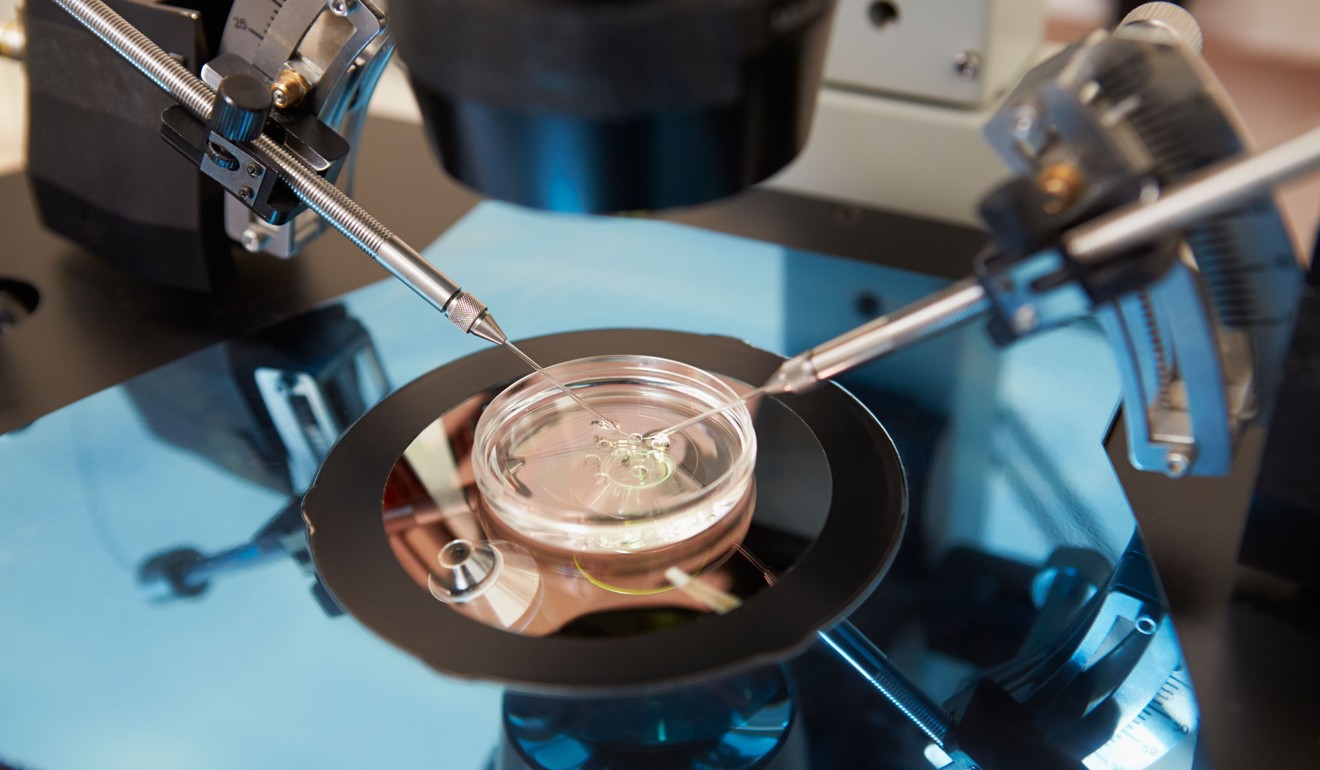

The couple chose to undergo assisted conception. Janner was 34 at the time. After four unsuccessful intrauterine insemination (IUI) cycles in Hong Kong, the couple opted for in vitro fertilisation (IVF) in Hong Kong and Australia, to much heartbreak and devastation.

The first attempt failed. Another attempt led to a pregnancy, but at nine weeks, the doctor couldn’t find a heartbeat. In Australia at the time, she later miscarried.

But this wasn’t the toughest test. Another IVF attempt resulted in an ectopic pregnancy that lead to the loss of a Fallopian tube. She sought counselling in Hong Kong to cope with the aftermath.

Janner says IVF was more affordable in Australia, where patients taking part in the process have free and unlimited access to a psychologist.

“It was part of the process – you met with them before the IVF and then discussed whether it was successful or not. I found that really good,” she says. In Hong Kong however, where she sought counselling after the ectopic pregnancy, she found the experience restrictive, including the type of expert she could consult, limited by her health insurance.

“In Hong Kong, it’s more business-driven. If you want to see someone, you have to pay for them; it’s not part of the service, even though IVF is more expensive here than in Australia,” Janner says.

The biological clock ticks for men too, researchers find, with odds of parenthood falling with age

As more couples have children later, particularly in their late 30s and 40s, many encounter fertility woes and seek help. However, the emotional work that goes into assisted conception is notoriously difficult.

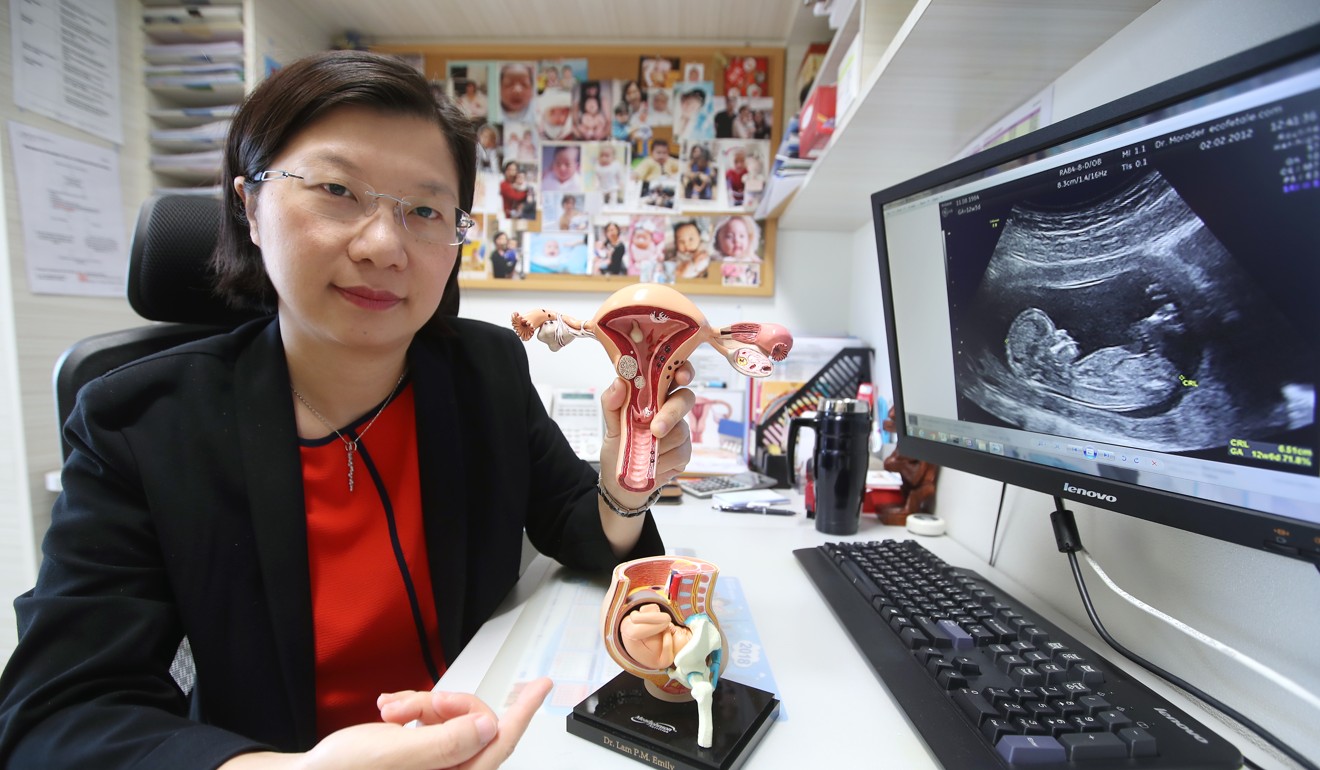

Dr Emily Lam Po-mui, a specialist in obstetrics and gynaecology, says this journey often disrupts couples’ lives, and can even sink marriages. “It’s our duty to support them,” she says. “In Hong Kong, there is still a lot of room for improvement.”

In Hong Kong, the average marriage age was 29.4 for women and 31.4 for men in 2016. Lam says women tend to wait years – to develop their career, for example – before attempting to have a family.

She says couples often hesitate before seeing a fertility specialist as the wait time to see a doctor, especially in the public sector, is around two years or more for the first consultation. She estimates the average age of IVF patients is 38 or 39.

A woman’s age is a key factor in treatment outcome. The best time for childbearing is before 30; after 35, a woman’s fertility drops sharply.

“Before 35, the success rate is more than 50 per cent, whereas from 35 to 37, the rate is 42 per cent per IVF cycle, which is still OK. From 38 to 40, it’s around 26 per cent. Beyond 40, the success rate is less than 15 per cent,” Lam says. Even with the aid of advanced reproductive technologies, a women’s ability to conceive at 40 or over is less than 15 per cent, she says.

Why Hong Kong’s birth rate is falling, and how sub-fertile couples can conceive

“The older you are, the lower the success rate,” she explains, adding that reproductive technologies cannot reverse fertility odds, including one’s egg quality, which diminishes as women get older.

In Hong Kong, fertility-challenged couples are less likely to seek medical help.

“In the European and American countries, studies showed that around 15 per cent of those seeking medical consultation after realising [they had] infertility problems would receive fertility treatments like IVF and IUI,” says Dr Alexander Doo, a specialist in obstetrics and gynaecology, in a press statement on behalf of the Hong Kong Society for Reproductive Medicine.

“With reference to the European and American countries’ figures, there should be about 10,600 people in Hong Kong receiving the infertility treatment. However, the statistics of the Council on Human Reproductive Technology reported that only 6,200 people [in Hong Kong] received assisted reproductive treatment in 2016, 40 per cent lower than that of the European and American countries,” Doo says.

The dilemma facing Hong Kong’s expectant mums: follow traditional Chinese beliefs or ways of the West?

It is believed that misconceptions about this process deter couples from seeking help, including the view that these procedures are painful and harmful.

Lam clarifies that while hormone injections to stimulate ovary production are required for IVF patients, the experience is similar to insulin injections diabetics require to keep their sugar levels at bay.

Couples need to face the problems and stress, and talk more about it themselves and to medical staff, too.

Not all patients need such advanced treatment, she notes. Other ways to attempt to conceive include IUI, which is not necessarily painful. Treatments depend on a couple’s situation.

Another major force contributing to the low uptake of assisted conception is the stress arising from infertility, and lack of psychological support for couples facing it. Lam acknowledges that the field has paid more attention to technological advances in reproductive technology than the stress and mental hardship facing childless couples.

“Throughout this process they need support from their partners and family. But they also need it from medical staff, because we know their situation, the psychological stages that they need to go through before they can accept and receive the treatment,” she stresses.

More than 77 per cent of couples drop out during the process due to “pressure and emotional disturbance associated with treatment,” Lam adds.

The Hong Kong Reproductive Medicine Centre and the University of Hong Kong have jointly organised a certificate in infertility counselling programme to equip professionals in the field with psychological and interpersonal skills to aid patients.

“We need to [help] medical staff to spot high-risk couples, so if they have problems, we can offer some simple psychological counselling or support; or, for severe cases, refer patients to psychologists or psychiatrists for treatment,” Lam explains.

Different levels of counselling may be needed at different stages. Managing hopes and expectations is essential. For instance, couples expecting success after their first IVF attempt need a reality check.

“Fertility treatment is a troubleshooting process. We need to find the problems and overcome them through advanced technology, and sometimes that takes multiple steps,” she says.

More Hong Kong women to have multiple babies per pregnancy as use of fertility technology rises

Even after conception, the challenges do not end. Couples often have anxiety over a stable pregnancy. “Couples need to face the problems and stress, and talk more about it themselves and to medical staff, too,” Lam advises.

For Janner, the stress continued after successful conception through IVF.

After multiple failed attempts in Australia, she finally became pregnant after the fourth cycle in 2015. Excitement quickly morphed into anxiety over the baby’s health.

Bad news hit at nine weeks. Doctors discovered Janner had a life-threatening complication, with the potential to cause her to bleed out and die if she continued the pregnancy.

She recalls that fateful Saturday morning on the operating table. “The nurses were crying, I was crying,” she remembers. The night before, the tears had flowed endlessly as she visited a priest over the prospect of terminating the pregnancy.

Should dads be in the delivery room? We look at the pros and cons

In the operating theatre, though, the doctor examining scans noticed the fetus had shifted position, and alerted Janner to the “miracle”. “I said I would sign a waiver if I had to, but I would not terminate my baby,” she recounts.

She was in hospital for months before the birth to monitor her high-risk condition, but she had faith the baby would come to term. “If I die, I die, but I’d rather die trying then spend the rest of my life in regret if I terminated,” she says. This was tough for her husband, she adds, who sprouted grey hair during the ordeal.

In January 2016, their son was delivered by caesarean section. “I thought it was a dream, that I’d wake up and someone would take him away,” she says of that first month.

Today, Janner beams over her hyperactive two-year-old. And she is back on IVF after the latest attempt failed in August.

“I know, I’m crazy,” she says. “I’m greedy, I want another one.”