Commentary: how David Bowie stood out from baby-boom rock stars

The generation that led the golden age of rock gave us a new sense of possibility in the 1960s. One man kept pushing the boundaries through the next five decades

“Most rock stars are about 70 years old these days,”wrote the music critic Kate Mossman on the death in 2013 of American musician Lou Reed, and she was not wrong. Fifty or so years after they began blazing a trail into a new world, we refuse to let go of the pop-cultural generation born in the 1940s, even though most of their creative lights have long since dimmed.

However, that is hardly the point. When the Rolling Stones played Glastonbury in 2013, I watched a crowd of twenty-somethings stand within eyeshot of the main stage, wait for a close-up of Mick Jagger on the big screens, take selfies, and then disappear again. Evidently, the performance was less something to immerse oneself in than a kind of living Mount Rushmore.

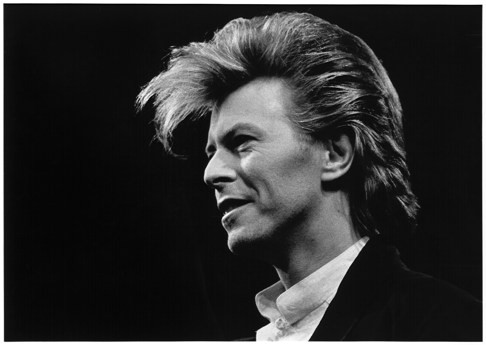

Even at 69, David Bowie was a bit different. Though he decisively arrived in the 1970s, he was essentially part of the same cohort as the icons of the 60s, and a collaborator and friend to Reed, Jagger and John Lennon. But whereas most surviving veterans of those decades had long since resigned themselves to becoming real-life monuments, he was restless and creative to the last.

One play of 2013’s supposed comeback album, The Next Day, was enough to prove that he still had lots to say. Moreover, Blackstar, apparently created in the knowledge he did not have long to live and released two days before he died on January 10, is a very good record indeed: exploratory, unsettling, the work of someone still ready to take inspired risks.

The achievements of the latter album informed the almost perplexed response to his death: how could an artist be in apparently full flow, just as he was taken away? But in much of what has been said, there has also been a clear sense of something historic afoot: the passing of one of the most pre-eminent members of a golden generation, confirming that no matter how much we hang onto them, they are now leaving us, at speed.

Reed, Joe Cocker, Cream’s Jack Bruce, good old Lemmy from Motorhead: the obituary columns of rock magazines are now routinely full to bursting. But Bowie was the individual who most spectacularly embodied the wonders of the era that arrived just in time for his 20s, and the way that a few people succeeded in forcing open doors that older, more conservative elements had long insisted remain locked.

In among the blizzard of tributes on Twitter, the writer Jon Savage called him a “major liberator”, which perfectly nailed the point. Here, after all, was an artist positioned to somehow lead people into the future, who well knew it. As much as endlessly inventive music and lyrics, this is what you hear in his best songs: from the glorious raunch of Rebel Rebel to the epic six minutes of Heroes, the chaotic, cacophonous modernity in which we still live, when it was all new.

Where did it all come from? The details of Bowie’s early life speak volumes about the historical circumstances that made him. He was born only 17 months after the surrender of Japan, to parents whose adult lives had been defined by the second world war (his father served in Europe and north Africa). A nicely topical note: despite passing his 11-plus, he precociously insisted on being educated at Bromley Technical school, a place apparently designed to produce commercial artists and engineers, where the art department was run by a teacher – the father of Bowie’s future collaborator Peter Frampton, as it turned out – who fired up his pupils’ creativity and curiosity.

Later on, after first attempts at a career in music, Bowie sampled the creative whirl that had been sparked by the UK’s art schools in an enterprise called the Beckenham Arts Lab, and studied dance and mime under the choreographer Lindsay Kemp.

In the background, relative popular affluence and the expansion of education were widening horizons, at the same time as simmering ideological conflict fed the idea that art should ask uncomfortable questions: in cultural terms at least, the England of bowler hats and class distinctions was vulnerable as never before.

Most importantly, this was the age in which a new sense of individuality replaced the idea of meekly taking one’s place in the masses. The political left looks back at this period as one of revolt and rebellion; it is equally true to say it spawned the modern individualism so beloved of the right. There is no resolving this tension and in terms of art and music, it doesn’t really matter. The point is, if you were in the right place, everything seemed to be in a state of ferment, and for a few extremely talented people, the stage was set.

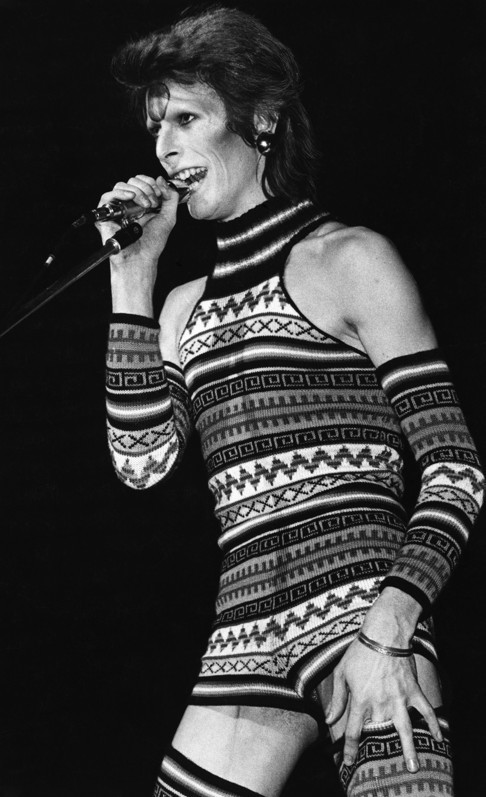

The Beatles’ rise was framed in terms of the shoving-aside of old hierarchies; the Rolling Stones represented simple disobedience. But six years after those two groups reached their commercial peak, Bowie embodied something even more profound: as evidenced by the awed memories of people party to the legendary occasion when he played Starman on Top of the Pops, a self-expression so thoroughgoing that it defied received ideas not just about sexuality but gender – in, let us not forget, 1972.

I was too young to witness that, but I can vividly recall three other moments of wonder, again watched on TOTP: Boys Keep Swinging (1979), the unbelievably heady Ashes to Ashes (1980), and even the much more mainstream Let’s Dance, which seemed to sit at the top of the charts forever (I now discover it was a mere three weeks) in 1983. That song – and its video – had a sense not just of unsettling mystery, but thrilling possibility, captured in the passage that follows each verse, when Bowie declaims: “If you say run, I’ll run with you.”

Beyond that, I cannot even begin to articulate what it conveyed, though it felt – and still feels – really powerful: at a guess, like all the best stuff from what we might think of as the rock Age, it seemed to somehow survey its surroundings, upturn every certainty, and loudly say: “There is more than this.”

Rock music now seems to serve a different function. It is so ubiquitous – available for nothing, would you believe? – that it tends to either offer a comfy kind of reassurance or stand for nothing but itself. Meanwhile, as old barriers are put back up – something evidenced by everything from the loud return of feminism to renewed angst about class – mere singers and musicians seem little able to help. Shock was a big part of how we all responded to Bowie’s death, but so was something else: in all the recollections of this or that epiphany, belated mourning for a world in which art could fracture normality, an idea that now seems strangely quaint.

To quote the sighing chorus of one of his most moving recent songs, where are we now? All day, as the tributes extended into the distance, the other lyrics that kept popping into my head were not the work of Bowie, but Morrissey, one of the people he had changed forever, and who stood on his shoulders: “I know it’s over/Still I cling/I don’t know where else I can go.”

The Guardian