Westerners translate Chinese video games in a labour of love

Some dedicated fans have banded together to bring Chinese games to a wider audience

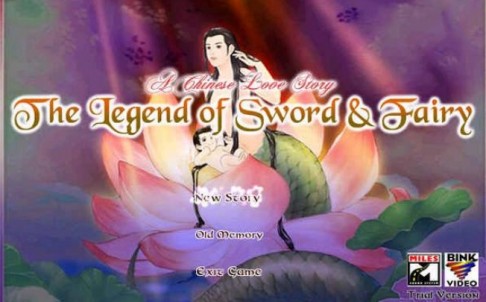

Magical swords, martial artists and a mystical setting – these all form the basis of The Legend of Sword and Fairy, a Chinese video game series.

Eighteen years after the first game was released by Taiwan-based Softstar Entertainment, The Legend of Sword and Fairy games continue to win praise in a local market that makes over a trillion yuan each year. Despite their domestic success, however, Chinese video games are largely unknown to international audiences, a puzzling fact considering the country's recent drive to push its culture abroad.

But this hasn’t stopped a dedicated group of non-Chinese enthusiasts from promoting games like The Legend of Sword and Fairy online.

“I grew up around computers and gaming, experiencing them as a positive family activity,” Brunskill says. “As an adult I simply wish to play good games, and it has become especially important to me to sample as much of my hobby as I am able to, which naturally leads me to the more obscure.”

Brunskill is not alone in her enthusiasm. As interest in the Chinese language increases amongst foreigners, several Western fans have banded together to create “fan translations”.

“I first realised that games could be hacked and translated from one language to another in 1996,” says Derrick Sobodash, an American-born journalist who learned Chinese in university. “There was a Chinese guy on my web forum who suggested looking into The Legend of Sword and Fairy. I did, and it just sort of took off from there.”

“I was adjusting to life in China and a full-time teaching job,” Sobodash says. “By 2006, I had decided the best course of action was to simply release my [translation] tools to the public and let someone else take over.”

With the help of Sobodash’s translated scripts, other fans picked up where he left off. The Legend of Sword and Fairy has seen numerous translation efforts over the last seven years, although the projects have stalled since 2012. On the other hand, a continuation of Sobodash’s work on Heroine Anthem persists on ROMhacking.net, and progress is slow but sure.

Translation patches like Sobodash’s lie in a legal “grey” area. Because the patches are distributed for free online and require users to technically own a copy of the game first, Chinese companies are unaffected and usually unaware that the translations even exist.

With C&E’s permission, Cobb and his team completed fully playable English translations of several games. The translations were sold for money and released in physical packaging in an effort to appeal to retro gaming enthusiasts – a rare occurrence in the fan translation world, but one made possible by the blessing of C&E. To this day, the company is most famous for its translation of Beggar Prince, a 1996 adventure title.

Super Fighter Team’s success leads to a bigger question – why have Chinese video games been ignored by official translation companies, and why must the fans be the ones to translate and distribute them?

Sobodash feels that big companies and the majority of gamers may be too accustomed to Japanese games, which are commonly translated and enjoy a massive international following.

Brunskill adds that rampant piracy in the Chinese game industry has not helped matters.

“There is something of a stigma associated with Chinese games - that China has produced nothing but endless pirated [software] and there's just nothing of value to look at,” Brunskill says. “That general feeling mixed in with the fact that Chinese games are very … text heavy and steeped in traditional … culture and imagery make them a hard sell, and more than likely a lengthy and costly localisation if any [company] ever were brave enough to take them on.”

Hard sell or not, fans like Sobodash and Super Fighter Team’s Cobb prove that Chinese games steeped in traditional culture aren’t enough to keep dedicated enthusiasts from taking translation matters into their own hands and doing what the big companies will not.

“I would be very happy if my only mark on the internet was raising awareness of Chinese games,” Brunskill says of her Shinju Forest website, which features an entire listing of The Legend of Sword and Fairy games. “I just hope that one day gamers will view them as a legitimate part of our hobby … There’s a market out there – a good game’s a good game, after all.”