Scientists look at ways to cool the planet through geoengineering

Scientists think it's now possible to cool the planet by geoengineering, but our complex ecosystem demands that plans proceed with caution, writes Jamie Carter

Climate change is an unintended by-product of the global industrial society we all live in - a horrible accident that can't easily be cleared up. But by studying its processes, scientists now think they can intentionally influence further change.

They're asking one of the biggest questions of all, one that could succeed nuclear weapons as this century's hottest debate; can we geoengineer a new climate? Technically, the answer is a simple "yes".

"It is possible to cool the planet by injecting reflective particles of sulphuric acid into the upper atmosphere where they would scatter a tiny fraction of incoming sunlight back into space, creating a sunshade for the ground beneath," says David Keith, professor of public policy at Harvard Kennedy School at Harvard University and author of new book, .

He calls such solar radiation management "cheap and technically easy", although he knows that talking about changing the weather is a touchy subject that risks moral outrage.

Such is the collective awareness of how sensitive and finely balanced earth's ecosystems really are that few are willing to play fast and loose with climate change. "Many people feel a visceral sense of repugnance on first hearing about geoengineering," says Keith, although he thinks that intuitive response is healthy.

"Our gadget-obsessed culture is all too easily drawn to a shiny new tech fix … a narrow focus on a technology's power too easily blinds us to its risks."

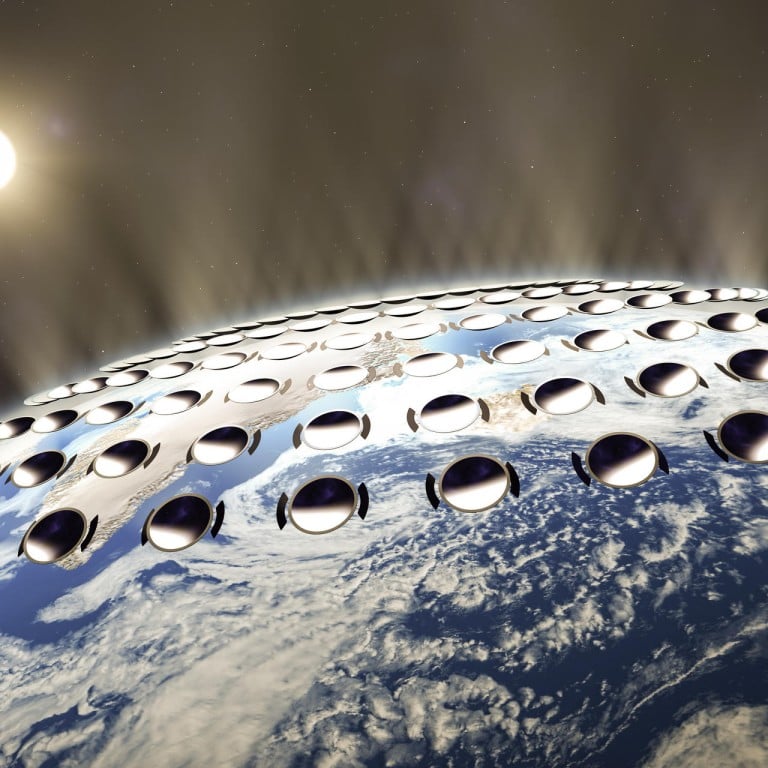

The most eye-catching solution of all - the construction of huge mirrors (or millions of small ones) in space to reflect sunlight - was mentioned in the same UN Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change report in September, which concluded that it's "extremely likely that human influence has been the dominant cause of the observed warming since the mid-20th century".

Our gadget-obsessed culture is all too easily drawn to a shiny new tech fix

Space mirrors might be unlikely, but Keith thinks we should seriously and rationally try solar radiation management because progress on cutting down on carbon dioxide emissions is just too slow.

Sulphate particles that reflect solar radiation back into space, launched into the stratosphere in huge balloons, will hopefully mimic what happens when a volcano explodes; aerosols from the eruption of the Philippines' Mount Pinatubo in 1991 - the 20th century's second-largest volcanic explosion - settled in the stratosphere and for three years reduced the amount of sunlight in the northern hemisphere.

Temperatures dropped by around 0.5 degrees Celsius, and masked the effects of background global warming.

The advantages of mimicking the effect of a volcano using solar radiation management could prove irresistible to future governments of countries struggling with global warming.

"This single technology could increase the productivity of ecosystems across the planet and stop global warming," says Keith, insisting that crop yields could be boosted, particularly in the hottest and poorest parts of the world.

In November, Ioane Teitiota from the Pacific island of Kiribati - which is threatened by rising sea levels - claimed asylum in New Zealand by calling himself a climate change refugee. Teitiota lost his case, although it underlines just how big an issue the world's changing climate is going to become.

Any venture to change the climate will come with huge risks. Just as global warming is having uneven consequences, it will likely also be the case in a geoengineered climate.

Geoengineering could reduce the monsoon rains in Asia, according to scientists at the National Centre for Atmospheric Research (NCAR) in Boulder, Colorado in the US. A study in October found that global warming caused by a massive increase in greenhouse gases would lead to 7 per cent more rain than in preindustrial conditions.

Start geoengineering the world's climate, and monsoonal rains in North America, East Asia and other regions could drop by up to 7 per cent. Average global rainfall could decrease by over 4 per cent.

"Geoengineering the planet doesn't cure the problem," says NCAR scientist Simone Tilmes, lead author of the study. "Even if one of these techniques could keep global temperatures approximately balanced, precipitation would not return to preindustrial conditions."

The science is simple. Less direct sunshine means less evaporation and therefore less rain, although when faced with more carbon dioxide plants partially close their stomata - the openings that allow them to take in the gas - so they release less oxygen and water.

"It's very much a pick-your-poison type of problem," says John Fasullo, NCAR scientist and co-author. "If you don't like warming, you can reduce the amount of sunlight reaching the surface and cool the climate. But if you do that, large reductions in rainfall are unavoidable. There's no win-win option here."

The consequences of geoengineering could be dangerously geopolitical. "Even if it makes some farmers better off, others will be worse off," says Keith, who fears that geoengineering will be so cheap that every country will be able to afford it - and thus blame each other for a sudden lack of rainfall or other changes in local weather patterns.

A drought or flood would bring immense political pressure to halt geoengineering projects, which could lead to even worse environmental consequences. Filling the stratosphere with aerosols to halt global warming could, if not done carefully as part of an interrupted long-term strategy, badly damage the ozone layer.

The Geoengineering Model Inter-comparison Project reported recently that a sudden halt to a 50-year-long geoengineering project of solar radiation management would result in a rapid increase in global mean temperature.

The widespread use of geoengineering also could shift the balance of global power - and even lead to war. "It may prove as disruptive to the political order of the 21st century as nuclear weapons were for the 20th," says Keith.

Geopolitically, solar radiation management may not be the wisest move, although it's just one of a number of technologies that scientists could use to mitigate the warming climate. Keith himself is president of Carbon Engineering, based in Calgary, Canada, which focuses on the main alternative to solar radiation management - carbon dioxide removal.

A quarter of all the carbon dioxide on earth was produced in the past decade, and without help won't disperse for centuries.

Carbon Engineering's process, Direct Air Capture, uses an alkaline hydroxide solution to absorb carbon dioxide from the atmosphere, which is then made into pure compressed carbon dioxide. It can then be used in industry as a fuel or buried.

Another way is to use plants to absorb carbon dioxide. Haida Salmon Restoration Corp, a marine research company in Old Massett, British Columbia, Canada, has previously experimented with "iron seeding" in the North Pacific; the dumped iron particles encourage the growth of plankton, which feeds the small fish that salmon eat.

But the plankton also absorbs carbon dioxide. The project in late 2012, which saw 100 tonnes of iron sulphate and 20 tonnes of iron oxide dumped in the ocean, was controversial. The resulting salmon run is due some time this year.

Tilmes thinks that more research is needed into geoengineering, but she's cautious. "Our climate system is very complex ... and that any technological fix we might try to shade the planet could have unforeseen consequences."

Politicians will likely soon be tempted by geoengineering as an excuse not to address carbon dioxide emissions.

But could a scientifically sound global plan spanning generations be agreed on at the UN and executed without meddling from politicians?

Geoengineering seems, for now, just a lot of hot air.