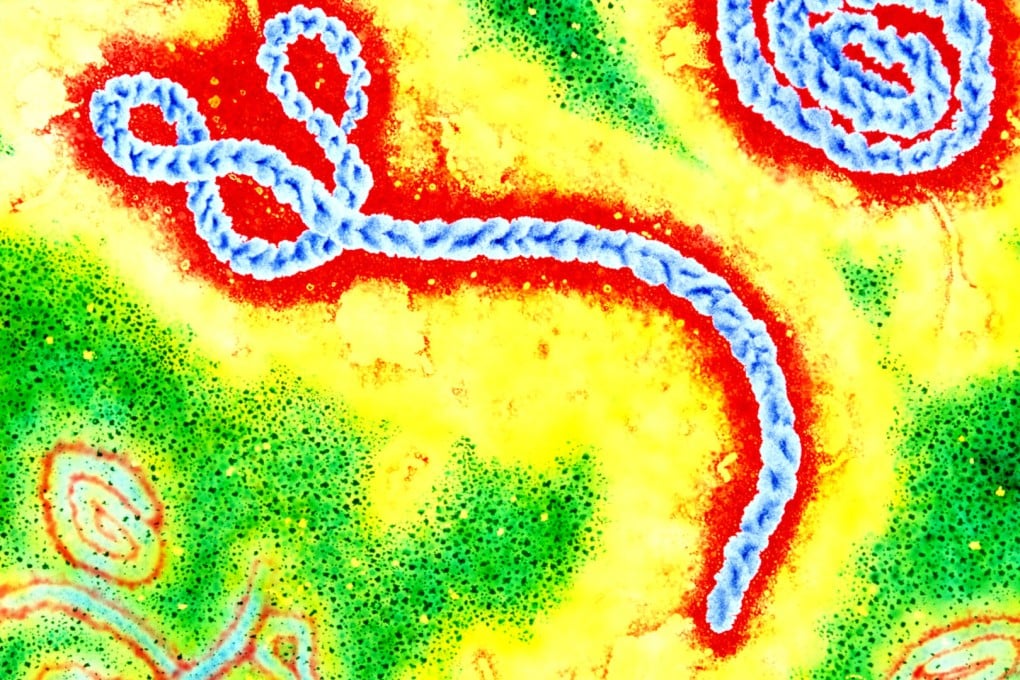

Scientists are closing in on drugs that may stop the deadly Ebola virus

Disease still kills 90pc of its victims, four decades after emerging, but treatments entering the trial stage may change that frightening statistic

Almost 40 years after Ebola emerged from the jungles of Africa as one of the world's most lethal diseases, scientists are beginning to close in on treatments that may be able to stop the virus.

The relative rarity of Ebola outbreaks, and the fact that they are largely limited to rural areas of poor African nations, makes the disease an unattractive target for big drugmakers. Instead, much of the research has been funded by the US government. Tekmira Pharmaceuticals, for example, began its first human trial of a drug in January with backing from the Defence Department.

"There are already candidate cocktails that can be used in an emergency," said Erica Saphire, a professor at the Scripps Research Institute in La Jolla, California, who is leading a consortium of 15 public and private institutions to develop treatments to fight the virus. "It's a really exciting time to be working on Ebola."

The WHO had not requested emergency use of any experimental treatments that had not been through the necessary clinical tests, said Tarik Jasarevic, a spokesman for the Geneva-based agency.

Trials showing the drugs were safe, plus ethical and regulatory clearance from the health ministries of affected countries, and regulatory clearance from the country where the drug was made, would be needed before any experimental treatments could be used in an emergency situation, said David Heymann, a professor of infectious disease epidemiology at the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine. He has worked on Ebola since the first outbreak in 1976.