Hong Kong’s secret, illegal e-bikers crying out for power to the people

E-bikes are cheap, quiet, environmentally friendly, take up much less space than cars and are used all over China – so why are they outlawed on Hong Kong roads?

Rush hour in Fuzhou, capital of Fujian province and home to 6.6 million people, seems unusually quiet. It’s not the density of traffic on the roads that is remarkable, but the lack of noise.

It’s almost completely silent because most commuters in Fuzhou, like an estimated 200 million others across China, opt for electric bikes – and it’s easy to see why. These two-wheeled vehicles, which range from electrically assisted bicycles to what appear to be silent conventional motor scooters, seem to offer the perfect solution for urban transport. E-bikes are cheap, quiet, have zero emissions and take up much less space than cars. Batteries can be conveniently charged overnight at home and they have inspired a successful Chinese industry which supplies customers all over China and the rest of the world.

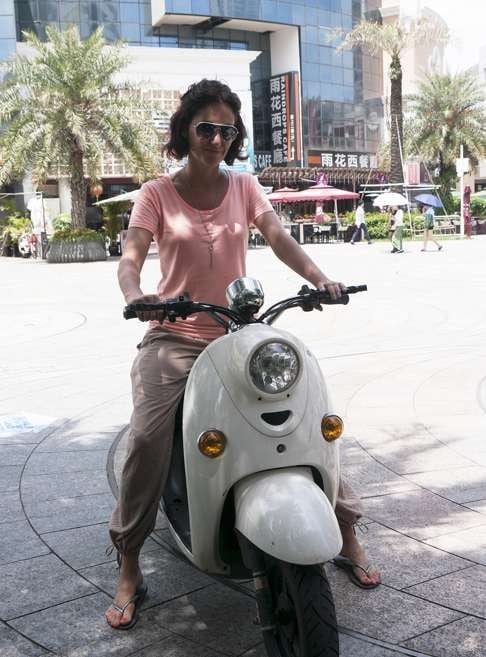

“I love it. It’s the best thing about my life in Shenzhen,” says Audrey Tournier, a French entrepreneur who runs her own organic beauty products company in the city, as she parks her elegant white electric scooter outside a coffee shop in Shekou. She says she bought it about a year ago for 3,800 yuan (HK4,400) and uses it all the time with no problems.

She is just one of an estimated 39 million people who purchased e-bikes in China last year; according to Ma Zhongchao, of the China Bicycle Association, electric bikes have become the most widely used means of transport in parallel with the nation’s rapid urbanisation. And it’s not just China where these environmentally friendly two-wheelers are proving popular. The EU’s 28 member states imported 551,782 e-bikes in 2012, mostly from China, and the numbers are on the rise. That’s a lot of people not in cars and buses spewing out CO2. Even safety-conscious Singapore has embraced the e-bike albeit with a raft of sensible regulations and control measures.