Six of the best wildlife-spotting locations in South and Southeast Asia

There are plenty of ways to see the world’s most fascinating and rare animals without doing them any harm. Here are some of the region’s hot spots

From the Tonkin monkeys of Vietnam to the leopards of Sri Lanka, South and Southeast Asia has an abundance of incredible wildlife to draw in tourists. The tarsier sanctuaries on Bohol in the Philippines are protected enclosures, but large enough for the tiny creatures to feel wild. National parks offer a chance to see animals in their wild and natural state. In some places, such as the Cardamom Mountains of Cambodia, wildlife tourism can even contribute to preventing poaching, protecting the environment and the local wildlife.

Any animal lover will want to experience these amazing creatures without doing them any harm.

There are a few simple rules to follow: look, but don’t touch; keep your distance and try not to disturb the animals. It helps to always travel with a reputable operator, one that has a good record and policy on animal welfare. If in any doubt that you might be causing stress or harm to animals, raise the issue with your guide.

Are you contributing to animal abuse? Attractions to avoid on your next holiday

What was once one of the last strongholds of the Khmer Rouge is now one of Southeast Asia’s great wildlife conservation success stories. The Cardamom mountains are home to some of the densest and most wildlife-rich rainforests in Southeast Asia, the second-largest contiguous rainforest in the subregion.

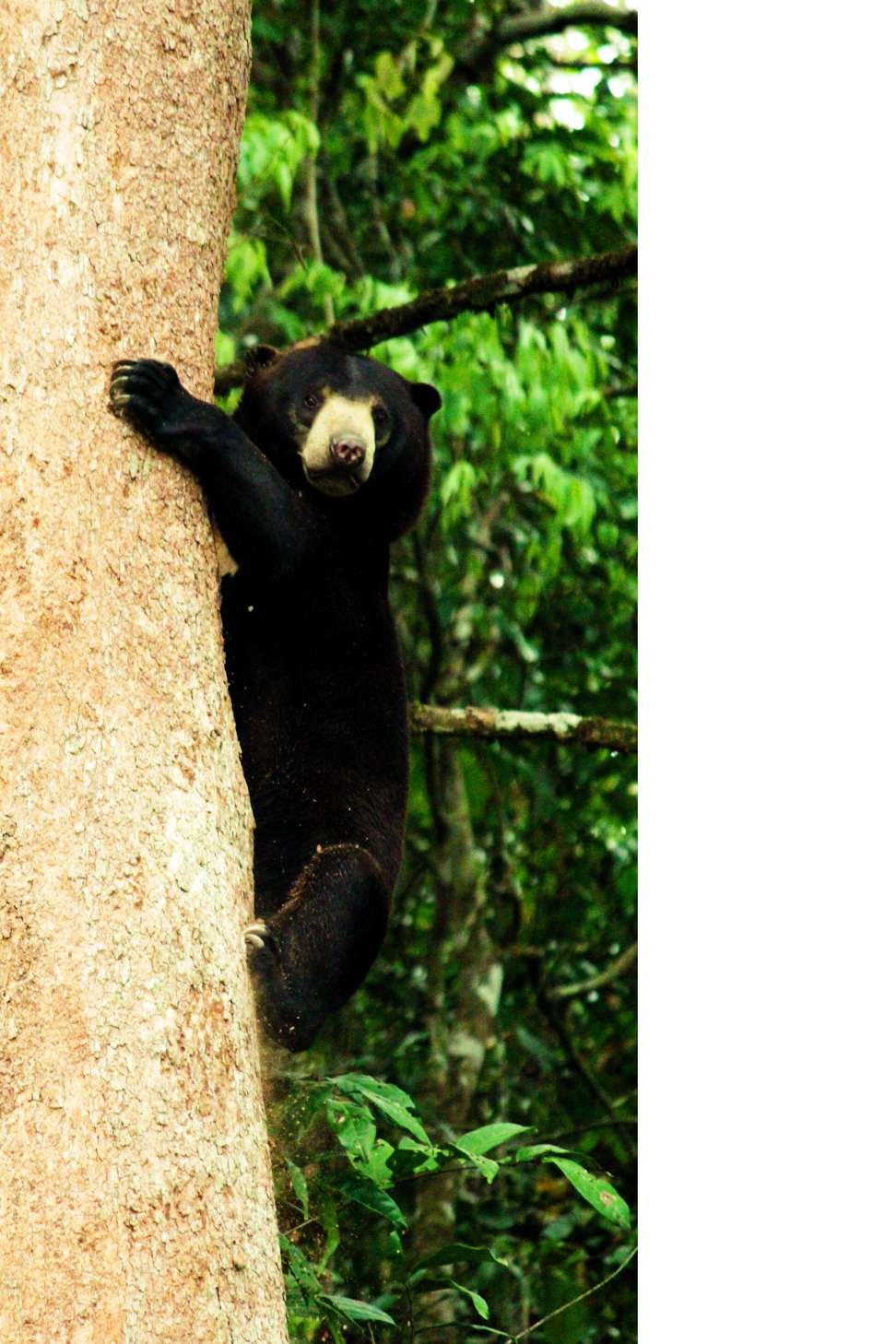

There was good news in 2016 when the Cambodian government designated more than 1,600 square kilometres of land across the mountains as a national park, now the Southern Cardamom National Park. It joins six existing national parks to create a vast 18,210 square kilometre protected area, a vital wildlife corridor and one of the last remaining habitats for wild Asian elephants, Indochinese tigers, clouded leopards, Asiatic black bears, Malayan sun bears, Irrawaddy dolphins, Siamese crocodiles and many more precious species.

Rainforest Trust, Wildlife Alliance and their local partners have worked to protect the biodiverse region from logging, mining and industrial development, while locals who previously poached the wildlife are now employed as local rangers and guides, protecting the animals they once hunted.

It’s thought that the Cardamom Mountains are home to thousands of as-yet-undiscovered species of flora and fauna, valuable species that might have disappeared if planned industrial development had been allowed to go ahead without interference.

Formerly a hunting ground for the British during colonial rule, Yala National Park is now a protected area covering more than 900 square kilometres, making it one of Sri Lanka’s largest national parks. It’s also the busiest and most popular park in the country, largely because of the mammals found here.

Situated in the southeast of the country, the grassy plains and tangled forests are a playground for a thriving population of Sri Lankan leopards, a subspecies endemic to the country. In fact, the national park boasts the highest density of leopards in Asia, as high as one cat for every square kilometre.

During June and July, sloth bears are often seen. Other animals you might observe include sambar (a kind of deer), spotted deer, buffalo, wild pigs, mongooses, langurs, jackals, Indian palm civets, and crocodiles.

For wildlife spotting, it’s best to visit Yala in the dry season, between February and June, when lower water levels make it easier to spot animals coming out to the lagoons to drink.

Yala’s diverse landscapes, including shallow lagoons, wetlands and pristine coastline, make it an excellent place to see colourful and varied birdlife, with more than 400 bird species, including 33 that are rare and endemic, recorded in the park. You could see anything from blue-tailed bee-eaters to black-necked storks.

Twitchers might also want to make a beeline for Bundala National Park, about an hour away, or to the Palatupana Salt Pans to see migrating shorebirds.

Taman Negara national park was the first officially protected area in Malaysia. It’s the country’s largest national park and one of the world’s oldest rainforests.

It’s rare to catch a glimpse of residents such as the Asian elephant, rhinoceros, clouded leopard and tiger, but Taman Negara is a chance to experience life in one of the world’s most untouched primary rainforests. The 4,343 square kilometre national park is also home to more than 50 species of bird, many brightly coloured butterflies, an array of primates, lizards, snakes, deer and tapirs.

The great hornbill is one of the larger and more colourful native birds in the park. Its impressive size and colour have made it an important part of many local tribal cultures and rituals. There’s the chestnut-breasted malkoha, a colourful cuckoo which, contrary to expectations, builds its own nest and raises its own young. Look up in Taman Negara and you might also see the dusky-leaf monkey (spectacled langur).

Cambodia’s 2,700 square kilometre freshwater lake Tonlé Sap is so massive that the seasonal changes in its water levels cause the 120-km long Tonlé Sap River, which connects up with the Mekong on the edges of Phnom Penh, to change direction each year.

The lake is home to tranquil floating villages, including Prek Toal, with waterways where locals move around by boat and, in the cases of some of the children, small tubs.

The lake area is a rich biosphere, home to a number of water birds of global significance, including the spot–billed pelican, painted stork and milky stork.

More than 150 species of birds have been recorded in the reserve. Viewing platforms have been set up to offer excellent spotting opportunities, especially between December and April when the lake sees the heaviest concentration of birds. There are also crocodile farms around the lake.

After spending a day bird-watching and negotiating the waterways by traditional longboat, it’s possible to visit the stilted villages for lunch. But consider an overnight homestay for a chance to have dinner and drinks with a local family, an authentic experience of Tonlé Sap life.

Ba Be National Park in northern Vietnam is home to several rare species of indigenous wildlife, including the endangered pangolin, gibbons, and slow loris.

Also referred to as Ba Be Lakes, the national parkwas set up in 1992 as the country’s eighth national park, with more than 100 square kilometres of limestone karsts, mountains up to 1,554 metres in height and lush green forests, along with caves, waterfalls and lakes.

Tigers, leopards, black bears and crocodiles live here, though sightings of the mammals can be tricky. Common macaque monkeys are one of the most frequently sighted beasts. There are also more than 550 known plant species in the rainforest region and more than 220 bird species, including serpent eagles, the oriental honey buzzard, herons and colourful flocks of parrots. Adding even more colour to Ba Be are more than 350 butterflies, more than 100 species of fish and several different varieties of turtle.

The national park is also home to the highly at-risk Vietnamese salamander and one of Vietnam’s most endangered primates: Tonkin snub-nosed monkeys.

There are 13 different tribal villages in the area, including Hmong and Tay communities. Locals are allowed to fish, but not to hunt. It’s possible to take boat trips to caves, waterfalls and the local villages.

One of the world’s tiniest primates, tarsiers are not monkeys, as they’re often wrongly called, but part of the Tarsiidae family. They’ve previously been the victims of their own cuteness, with locals using them to turn a profit by capturing the shy little critters to pose for photos for tourists. They were also kept as pets. Those practices are now outlawed and the tarsiers are protected.

You can see them in two centres on Bohol, the Philippine island that’s also home to the Chocolate Hills: the Tarsier Sanctuary near Corella and the Tarsier Conservation Area near Loboc. They tend to sit in trees in a favourite regular spot, which makes finding them (with the help of local rangers) usually quite easy. If you see them, maintain a respectful distance, but have your camera at the ready.