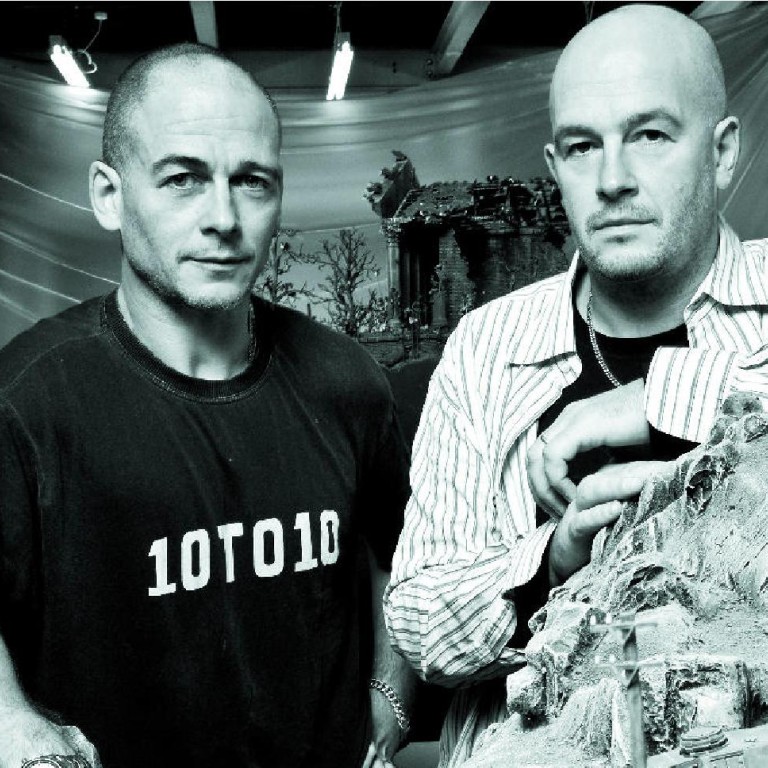

Brothers grim: all's fair in art and gore for the Chapmans

Their grotesque art disgusts and baffles, but Fionnuala McHugh discovers there is mirth in madness

HERE ARE SOME VITAL facts about Jake and Dinos Chapman, known simply as the Chapman Brothers: they are British artists. Their most famous work is titled Hell and their second-most-famous work is F***ing Hell. These underworld sculptures consist of thousands of tiny figures – many in Nazi uniforms – inflicting hideous acts of cruelty on one another.

This month, a series of similarly “underworldly” dioramas will be on show in Hong Kong, and will take up the entire ground floor of the White Cube gallery in Central.

When you’re on your way to interview the Chapman Brothers, however, what torments you are the stories of their run-ins with journalists. After well-known British interviewer Lynn Barber wrote about them, they threatened to kill her if they ever saw her again. Barber had asked Dinos during the interview whether his deformed hand (a result of rheumatoid arthritis) played a role in their London Royal Academy exhibition featuring deformed, anatomically jumbled mannequins of children – and Dinos did not take it kindly.

Five minutes into an interview with The Observer in 2006, Jake – finding the two questions inane – cut it short and the journalist was frogmarched to the door and chucked into the rain with the words, “Get out, just get the f*** out”.

These tales are not encouraging on a London afternoon of cruel wind and snow, and as your minicab driver gets lost on the way. The brothers have a studio near the now less glorious Olympic Stadium

The cab driver asks about the people at this mysterious address. When he hears that they have, among other activities, purchased watercolours by Adolf Hitler and reworked them, the driver – who is Polish – looks round in amazement. “Did Hitler have any talent?” he says.

The same question could be asked about the Chapman Brothers. The answer: it depends on whom you ask. As with all the so-called Young British Artists (YBAs), opinion is deeply divided.

“So, which is it, boys – are you clowns or monsters?” wrote the critic Johann Hari in a much-quoted 2007 piece. (Jake responded by calling Hari “fat-faced, ugly and four-eyed”.) The New Statesman also expressed a common concern, wondering “whether, like bullies watching a victim being mugged, they are simply standing on the sidelines, laughing”.

One unexpected fan among British art critics, however, has been Brian Sewell, 81, who is famous for loathing anything related to modern art (David Hockney: “a vulgar prankster”) and the YBAs in particular. Sewell championing the brothers’ abilities is about as likely as Leung Chun-ying extolling the Dalai Lama, and yet he has devoted columns to their brilliance.

“My view of Hell,” Sewell wrote in 2008, “was that when all the sharks have rotted, all the butterflies turned to dust and the Great Bed of Tracey [Emin] been consumed by moth, the Chapman Brothers will be the only artists of their generation to deserve more than a wry footnote in the history of art.”

Sewell has declared that if Hell (1999-2000) is the greatest work of art made in Britain at the end of the last century, then F***ing Hell (2008) is far and away the best made so far this century.

Once you enter the Chapmans’ homely studio, Hell and all its constituent parts are an active presence. Everywhere there are boxes of severed hands or heads; trays of tiny, manic Ronald McDonald’s teetering about on toothpicks (Ronald is a particular hate-figure in their iconography); and the torments endured by minute plastic models – disembowelled, garrotted, stabbed, sodomised, amputated. The boxes are attended to by 16 young technicians who are as blithely engaged as infants crayoning flowers.

Upstairs, in a corner of the office, a sculpture of a young girl smiles. She has two phalluses growing out of her head and her lower half is that of a centaur.

There’s a collection of bones on the floor. These belong to Buffy, Jake’s Staffordshire bull terrier, who crunches his way about the building. (A mouse, which ran across the floor during the interview, had no idea of the narrowness of its escape.) In such a context, even the Hello Kitty toothbrush left near a computer becomes a diabolical perversion.

Meanwhile, on another floor, Dinos, now 51, is tattooing 47-year-old Jake’s left arm with abstract squiggles using a machine he bought on eBay. There’s a constant hum as the needle makes contact with skin. As they’re both attractive men who manage to look at once twinkling and menacing, it’s like a clip from a Guy Ritchie film.

A suspicious journalist might wonder if this is a carefully choreographed scene – a metaphor for searing artistic creativity – but they are having too good a time to be bothered with what anyone else thinks (although, this being their general modus operandi, perhaps it is a living metaphor).

How painful is being tattooed? Jake: “It’s like a pin on sunburn.” Dinos (wielding the implement with a fiendish grin): “I lack empathy – that’s a good thing, not a bad thing.” Jake (thoughtfully): “Yeah, I couldn’t do it on him, I’m too squeamish.”

That being the case, you have to wonder where the roots of their disturbing visions spring from. They were born in England to a Greek-Cypriot mother, who named them Constantinos (Dinos) and Iakovos (Jake).

One might wonder if she perhaps suffered some wartime trauma, the awful details of which she might have passed on to her sons, sparking their taste for gore and macabre humour. But no, the Chapmans reject this line of inquiry, saying their mother grew up in Fulham, a generally massacre-free area of southwest London.

In fact, the brothers weren’t close as children. “We didn’t have much to do with each other because of the age difference,” Jake says.

Dinos states they had a proper conversation for the first time when, having studied art separately, they both enrolled on MA courses at the Royal College of Art and found they had something to say to each other. A sense of shared experience grew when they became assistants to artist duo Gilbert & George in the late 1980s, an apprenticeship that, Jake says, consisted of “colouring in Gilbert and George’s penises for eight hours a day”.

The Chapmans’ collaboration began in 1991. From the beginning, they were attracted to the grotesque, mutated and shocking – an artistic pursuit from which they have never, you could say, deviated.

“It wasn’t, ‘What can we do if we gang up together and be horrible?’,” Jake says. “The work is, if anything, a symptom of a perfectly wonderful childhood. We have no experience of war and torture, it’s a sublimated stand-in for an existence we haven’t had first-hand.”

And, apparently, it’s fun. “That’s the thing that drives us – the political importance of fun,” says Jake.

“Catastrophic fun,” adds Dinos.

This is the language of the cat, however, not the mouse Is it fun for observers who may have actually endured great suffering in, say, China?

“We want the work to be robust enough to take in local conditions wherever it goes,” says Jake, apparently the more cerebral brother and a follower of the French surrealist Georges Bataille, a man who liked to examine images of real-life torture and discuss the nature of evil.

“We’ve shown Hell in St Petersburg,” says Jake. That was last December; the show had 114 complaints and there was talk of possible prosecution.

“And we’ve exhibited in the Ukraine. But we don’t want different places to extort particular meaning. It’s the opposite of that. It’s about trans-temporal historicism. You can’t pick and choose the meaning - it’s a calamitous, catastrophic black hole of events.”

When Jake refers to Hell, of course, he doesn’t mean the original work which, in an event that surely proves the existence of divine comedy, was destroyed in a 2004 warehouse fire that also engulfed, among other YBA artefacts, Tracey Emin’s famous embroidered tent, titled Everyone I Have Ever Slept With 1963-1995.

The Chapmans say they laughed at the news: they got the infernal joke. Emin wasn’t amused, however, and refused an offer of £1 million (HK$11.9 million) from the Saatchi gallery to recreate her work. The brothers found her reaction so laughable that they claim to have made 5,000 Tracey Tents, one of which is erected in their studio and is nothing like the original.

“The thing is, she was gutted about the fire,” explains Jake. “The uniqueness of the work was the sticking point, she wouldn’t make another one. We thought, ‘Let’s rip it off! Make it better!’ The point about ideas is if they’re prohibited by possession, they’re not ideas – they’re acts of self-importance. We did it as a loving, generous act.”

“Tracey can’t even make her own bloody bed,” grins Dinos, referring to another of Emin’s famous installations – the rumpled, messy bed she created after a nervous breakdown.

This cavalier attitude to others’ creativity has divided critical opinion even more than the sexualised children and the diabolical sadism. In 2003, the brothers exhibited a complete set of 80 etchings of Goya’s The Disasters of War that they had bought, then defaced (the Chapmans prefer the word “rectified”) with images of clowns and puppies. The work was titled Insult to Injury. Plenty of observers found it an insult to their intelligence; some (including Sewell) thought it extraordinarily powerful, an effective update of Goya’s anti-war imagery.

In 2008, they did the same thing with the Hitler watercolours – 13 of them, bought as a job lot for £115,000. This time the “rectification” took the form of rainbows and smiley faces, after which the collective work (If Hitler Had Been A Hippy How Happy We Would Be) was sold for £685,000. With that sort of profit, the critical outrage must feel like a pin on sunburn.

White Cube’s Hong Kong show will include a new series of “reworked” paintings but it’s the Hell installation that will attract the most attention.

The visual concept isn’t new in China. If you travel to Fengdu, the so-called ghost city outside Chongqing, you’ll see identical torments – evisceration and mutilation – inflicted on miniature sinners in a Buddhist version of hell .

The scabrous, relentless and, yes, fun-loving Chapmans are making a global point with what they call their “joyful pessimism”. The pity of it is that the show’s title is ironic.

As Jake says, and this time he’s not joking, “It took us 2 ½-years to make 5,000 figures. It took the Nazis three hours to kill 5,000 people. The magnitude is beyond representation.”

“The Sum of All Evil” to refer to exhibition title instead of artwork, White Cube, 50 Connaught Rd, Central. May 22-August 31.